Fast Hydrogen Counting in SMILES

SMILES is the de facto standard for compact molecular representation in cheminformatics. One reason for its efficiency is hydrogen suppression, which has been covered here before. Of course, the thing about leaving hydrogens out of a molecular graph is that sooner or later they'll need to be put back in. There are many ways to do this, with varying costs. This article takes a look at this problem and proposes a simple, efficient solution.

But Why?

SMILES support is built into most cheminformatics toolkits which handle details like hydrogen counting, so why bother re-inventing the wheel?

It turns out that toolkits differ, sometimes by a lot, in how they count hydrogens in molecules built from SMILES. The situation has improved over the years, but issues remain. Knowing how to count hydrogens can help you debug problems seen in the wild.

Then there's performance. Cheminformatics toolkits are useful, but their generality incurs overhead. If your goal is to compute a molecular mass, a molecular formula, hydrogen bond donor-acceptor sets, or other descriptors, a cheminformatics toolkit may be overkill. Directly processing strings with an efficient low-level toolkit such as Purr may be all that's needed. Cutting corners becomes safer when you know the rules and risks.

Implicit Hydrogens

SMILES supports two forms of hydrogen suppression:

- Virtual Hydrogens. These hydrogens are defined as an attribute of a bracket atom. For example, the SMILES string

[CH4], assigns the carbon atom a virtual hydrogen count of four. The virtual hydrogen count of unbracketed atoms is zero. - Implicit Hydrogens. These hydrogens are obtained through computation on a bare (non-bracket) atom. For example,

Cdefines a carbon atom with an implicit hydrogen count of four. The implicit hydrogen count of bracketed atoms is zero.

Unlike virtual hydrogens, implicit hydrogens can only be counted using information outside of the SMILES representation itself.

SMILES Valence Model

SMILES solves the implicit hydrogen counting problem through its valence model. A valence model consists of two components: (1) a target valence table consisting of one or more target valences for each covered element; and (2) rules for using the target valence table.

The SMILES target valence table is:

| Element | TargetValences |

|---|---|

| B | 3 |

| C | 4 |

| N | 3, 5 |

| O | 2 |

| P | 3, 5 |

| S | 2, 4, 6 |

| Halogens | 1 |

The target valence table defines all of valence states covered by the model. If an element does not appear in the table, it's not part of the valence model.

To a first approximation, we compute implicit hydrogen count with the following procedure:

- Find the entry in the target valence table corresponding to the atom's elemental symbol.

- Find the atom's valence as the sum of bond orders.

- Find the smallest target valence greater than or equal to the valence. This is the atom's target valence.

- If no target valence exists, report an implicit hydrogen count as zero.

- Report implicit hydrogen count as target valence minus valence.

Consider methane (C). It has only one target valence entry, 4. The valence for this atom is zero because there it has no bonds. The target valence is four because that's the only entry. The implicit hydrogen count is therefore 4 (4 - 0).

A trickier example is tetramethylnitrogen (N(C)(C)(C)C). Nitrogen has two target valences (3 and 5). The valence for the nitrogen atom is four. The target valence is 5 because it's the smallest target that doesn't exceed the valence. The hydrogen count on nitrogen is therefore 1 (5 - 4). This may seem counterintuitive, but it's important to realize that in the absence of an explicit charge present within a bracket atom, all SMILES atoms are neutral.

The rules presented here provide a good start, but there's more to the picture.

Aromaticity

All is well and good with the SMILES valence model until we encounter unbracketed aromatics, which are written as with lowercase letters (b, c, n, o, p, s). Consider fluorobenzene (Fc1ccccc1). All atoms are unbracketed, but what are the implicit hydrogen counts for the aromatic carbons?

Naively applying the valence model from the previous section yields an unsatisfactory answer:

- atom(1): 1H (0H expected)

- atom(2) - atom(6): 2H (1H expected)

What's missing is a kekulization step. Kekulization transforms a representation containing aromatic features into one that does not. This typically involves the promotion of the orders of alternating bonds from single to double. For example, kekulization of fluorobenzene comprised of lowercase carbons (Fc1ccccc1) yields FC1=CC=CC=C1 as one option.

Kekulization is a non-trivial operation in the general case. It requires a solution to the maximum matching problem, typically through the application of Edmonds' Algorithm. For large aromatic ring systems such as those found in polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, fullerenes, and nanotubes, the computational cost can be substantial.

Kekulization just for the sake of counting hydrogens will be overkill in many situations. Fortunately, there is an alternative.

Cutting Corners

Although kekulization itself can be costly, the net result is rather simple. Either a given atom's valence will increase by one or it won't. To understand why, recall that kekulization can only increment the order of at most one bond attached to a given atom. If more than one bond were promoted to a double bond at a single atom, that would lead to non-alternating double bonds.

The bonds of some atoms will remain unchanged after kekulization. Fortunately, they are easy to identify. The bonds of an atom whose current valence is equal to a target valence, or greater than the maximum target valence, will not be incremented. Doing so would lead minefield of problems that SMILES avoids, albeit implicitly.

In other words, we can avoid kekulization entirely by considering the much simpler problem of whether an atom's current valence is equal to a target valence or greater than the maximum target valence. If so, the atom's valence will not be incremented as a result of kekulization.

For example, furan can be encoded with lowercase atoms (o1cccc1). The oxygen atom has a valence of 2 and a target of 2. Therefore, the oxygen atom's valence will not increase after kekulization. The carbon atoms on the other hand each have a valence (2) that is less than the target valence (4). These atoms' valence will increase by one after kekulization.

Subvalence

There's a foundational concept hiding just below the surface of all this, something I call subvalence. Subvalence is a non-negative integer representing the number of valence increases an atom can undergo without exceeding its current target valence. If valence already exceeds the maximum target, subvalence is zero.

Subvalence helps formalize the rules around implicit hydrogen counting for aromatics. If an aromatic atom's subvalence is greater than one, report implicit hydrogen count as subvalence minus one. Otherwise, implicit hydrogen count is zero.

Returning to the example of furan (o1cccc1), the oxygen atom has a subvalence of zero, so its implicit hydrogen count is also zero. Each carbon atom reports a subvalence of two, so the implicit hydrogen count will be one (2 - 1).

Tangentially, subvalence can also be used during kekulization. Atoms with zero subvalence are not considered for bond order adjustment. For example, the oxygen atom of furan would not participate in bond order promotion, but the carbon atoms would.

Expanded Rules

Putting everything together, we obtain the following revised set of rules for computing the implicit hydrogen count of an unbracketed atom.

| Element | TargetValences |

|---|---|

| B | 3 |

| C | 4 |

| N | 3, 5 |

| O | 2 |

| P | 3, 5 |

| S | 2, 4, 6 |

| Halogens | 1 |

- Find the entry in the table corresponding to the atom's elemental symbol.

- Find the atom's valence as the sum of bond orders.

- Find the smallest target valence greater than or equal to the valence. This is the atom's target valence.

- If no target valence exists, report an implicit hydrogen count of zero.

- Compute subvalence by subtracting valence from target valence.

- If the atom is not lowercase, report implicit hydrogen count as subvalence.

- If the atom is lowercase, report implicit hydrogen count as either subvalence minus one for subvalences greater than one, or zero.

To be clear, these rules apply only unbracketed atoms. The star atom (*) and all bracket atoms always have an implicit hydrogen count of zero.

Valence

The procedure described here assumes a reliable method for computing valence. Valence is a computation that sums an atom's bond orders. SMILES lacks the concept of bond order, instead defining one of eight bond types. The trick is to derive a reasonable bond order from each type. Here's one approach:

- single (

-): 1 - double (

=): 2 - triple (

#): 3 - quadruple (

$): 4 - up (

/): 1 - down (

\\): 1 - elided (blank): 1

- aromatic (

:): 1

These assignments, together with the rest of the valence model presented here, reproduce the implicit hydrogen behavior of major implementations and the documentation available from Daylight and OpenSMILES.

However, SMILES is a language with a universe of representations whose meaning and even validity are far from clear. Consider these examples, in which bond types other than aromatic or elided appear between lowercase atoms:

c1cc-ccc1. There is a maximum matching that produces benzene, but there is also one that must promote an explicit single bond to a double bond. Implicit hydrogen count is one either way.c1cc=ccc1. There is a maximum matching that produces benzene, but there is also one that produces benzyne by promoting the explicit double bond. Implicit hydrogen counts are one and zero, respectively.c1cc#ccc1. Some attempts to kekulize will lead to pentavalent carbon, others to benzyne. Implicit hydrogen count will be zero either way.

Unfortunately, SMILES descriptions are for the most part silent on this topic. Neither descriptions nor examples appear in Daylight online documentation, Weininger's SMILES paper, and Weiningers extended description.

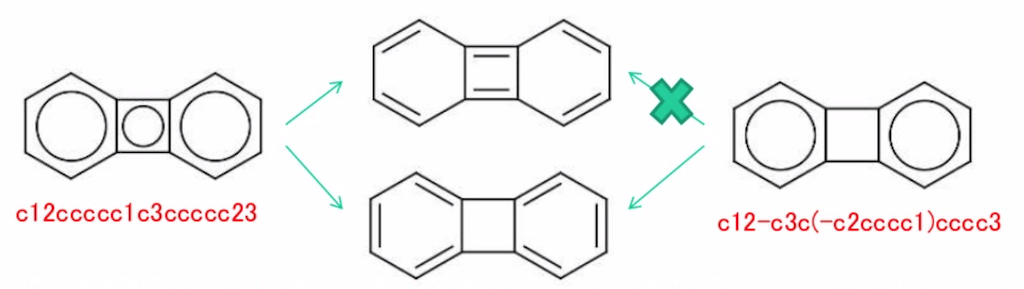

OpenSMILES partially addresses the issue by explaining that at least the single bond type between two lowercase atoms, as in biphenyl (c1ccccc1-c2ccccc2), is legal:

"… a bond between two aromatic atoms is assumed to be aromatic unless it is explicitly represented as a single bond '-'. However, a single bond (nonaromatic bond) between two aromatic atoms must be explicitly represented. …

How should we interpret c1cc-ccc1 in light of this guidance? It's not clear because the meaning of "assumed to be aromatic" isn't clear. If the meaning is that the bond order of the single bond can never be promoted, then application of the maximum matching procedure leads to a specific kekule form of benzene and all is well. However, extending this interpretation to c1cc=ccc1 leads to a cyclocumulene (C=1C=C=C=CC=1) and an implicit hydrogen count of zero. The contradiction remains.

In a 2017 presentation, Noel O'Boyle reiterated the OpenSMILES interpretation. In a nutshell, it states that the single bond type is not to be promoted to a double bond through kekulization. Its terminal atoms may contain other bonds that will be promoted. One motivation could be improved performance. In biphyenylene the technique restricts the range of possible mesomers, which may be helpful for depiction.

Then there's the aromatic bond (:). What's its purpose? In one interpretation, it does nothing at all - ever. In another, it could signify that non-lowercase terminals should be eligible for kekulization, as if they were written lowercase. Sources have something to say, but not much.

OpenSMILES instructs:

The aromatic-bond symbol ':' can be used between aromatic atoms, but it is never necessary …

Weininger's original SMILES paper notes:

Single and aromatic bonds may be, and usually are, omitted.

In other words, the aromatic bond is optional in the same way that a single bond is optional. The SMILES strings c:1:c:c:c:c:c:1 and c1ccccc1 both represent the same molecule, benzene, just like C-1-C-C-C-C-C-1 and C1CCCCC1 both represent cyclohexane. As far as fast hydrogen counting is concerned, an aromatic bond behaves like an elided or single bond.

What isn't clear is the meaning of a SMILES like C:1:C:C:C:C:C:1. Is this benzene or cyclohexane? Is it even valid? A small Twitter survey illustrates the confusion:

The SMILES C:1:C:C:C:C:C1 represents

— Rich Apodaca (@rapodaca) December 30, 2020

Depending on your perspective on these topics, the procedure you use for hydrogen counting may need to be adapted.

Limitations

The main limitation of the procedure outlined here is that the aromatic π-system of the SMILES representation never gets validated. This is but one of numerous semantic issues that can consume a rather large number of lines of code, such as: ring closure digits that don't match or which are duplicated on the same atom; negative implied neutron count; negative implied valence electron count; and so on. If you doubt the quality of the SMILES you're working with, you may need a more comprehensive solution.

Previous Work

To my knowledge, the first mention of the basic idea presented here occurred on the OpenSMILES mailing list. The proposal there differs from the one here in some important ways. More recently, John Mayfield proposed a similar idea, along with a few alternatives.

Conclusions

Implicit atomic hydrogen count is a computed property in SMILES. The computation is straightforward for bracket and aliphatic atoms, but more complicated for aromatics. The problem can be efficiently solved in most cases by correcting for the effect of kekulization. Ambiguous meaning and/or validity of certain SMILES constructs means taking a stand, but this is no different than using a toolkit.