A Comprehensive Treatment of Aromaticity in the SMILES Language

NOTE: a follow-up article is available.

Aromaticity pervades organic chemistry. Not surprisingly, it pops up in cheminformatics as well. But like many ideas in chemistry, reduction to software has a way of exposing hidden complexity. The SMILES language offers a case in point. Here the fuzzy notion of aromaticity collides with the rigor required by an information exchange format. Too often data loss, mangled data, and poor standardization prospects result.

This article proposes a comprehensive system for reading and writing aromatic SMILES. Grounded in graph theory, this approach plays well with some interpretations already presented in the literature and online. In other ways it parts company, but in a manner that is still compatible with current practice. What follows should be detailed enough to be reduced to practice within any cheminformatics toolkit.

Why Aromatic SMILES?

David Weininger's 1988 paper introduced SMILES. Under the heading "Aromaticity Detection," the author explains the purpose of "aromaticity" in SMILES:

Aromaticity must be detected in a system that generates an unambiguous chemical nomenclature. As will be discussed in following papers, this is needed both for the generation of a unique nomenclature and for effective substructure recognition. There can be no definition of "aromaticity" that is both rigorous and all encompassing; the word implies something about "reactivity" to a synthetic chemist, "ring current" to a NMR spectroscopist, "symmetry" to a crystallographer, and presumably "odor" to the original user of the word. Our objective in defining aromaticity is to provide an automatic and rigorous definition for the purposes of generating an unambiguous chemical nomenclature. Although the SMILES algorithm produces results that most chemists find natural, nothing is implied by this definition about physical properties.

As this passage makes clear, Weininger saw aromaticity as a way to enable what we now call canonicalization. Canonicalization is the process of choosing one of several possible representations for a chemical structure, an algorithm for which Weininger presents in a companion paper. As we'll see, Kekulé form conflicts with the goal of using SMILES as a unique chemical name. Aromaticity solved this problem by making only one representation possible.

In more concrete terms, Weininger saw canonicalization as a way to enable constant-time exact-structure match. As he later pointed out:

The availability of canonical SMILES allows "order 1" retrieval of structure- oriented information. This means that the time it takes to retrieve information for a given structure is completely independent of the number of structures which exist. … Remarkably, this is easily achieved using canonical SMILES and a technique called "hashing". The basic idea of hashing is to create a unique key (canonical SMILES) and treat that as the address of that key (memory address or disk position). …

The inclusion of "substructure recognition" as a goal deserves comment. Clearly, a cheminformatics toolkit capable of structure search is also capable of devising its own approach to resonance. But in 1988 there would have been only one system for reading or writing SMILES - Weininger's software, the internal consistency of which could be assumed. Today dozens of software packages read and write SMILES. They either assign aromatic features or not for a multitude of unknowable reasons. The aromatic features for a SMILES string of external origin should rightly be used only as a shorthand for Kekulé form or as an aid in canonicalization. Ascribing any other meaning for the purpose of speeding up substructure search or any other computation begs for trouble.

Delocalization-Induced Molecular Equality

Weininger's SMILES canonicalization problem can be generalized to a phenomenon I call delocalization-induced molecular equality (DIME). DIME can occur in Kekulé representations that can be rearranged without introducing additional charges or radicals. The result is two or more unequal Kekulé representations that must nevertheless be treated as if they were equal.

Consider 1,2-dichlorobenzene. When represented with alternating single and double bonds (Kekulé form), two unequal representations are possible. In one, a double bond joins the two carbons bearing chlorine. In the other, that bond is single.

Starting from the same atom and traversing the same spanning tree, two different SMILES will be produced depending on the resonance form being used:

C1=C(Cl)C(Cl)=CC=C1

C1C(Cl)=C(Cl)C=CC=1

The difference is purely an artifact of double bond localization required by the Kekulé form. A canonicalization system that allowed for such meaningless differences would need to chose one resonance form or the other. This would complicate an already complicated problem.

Aromaticity simplifies canonicalization by eliminating the meaningless distinction between equivalent ring bonds. Starting from the same atom and following the same spanning tree, aromaticity ensures that only one SMILES can be produced.

c1c(Cl)c(Cl)ccc1

Having established the goals and scope of aromatic SMILES, what remains are specific procedures for reading and writing. Before diving into that, however, one extra concept will be needed.

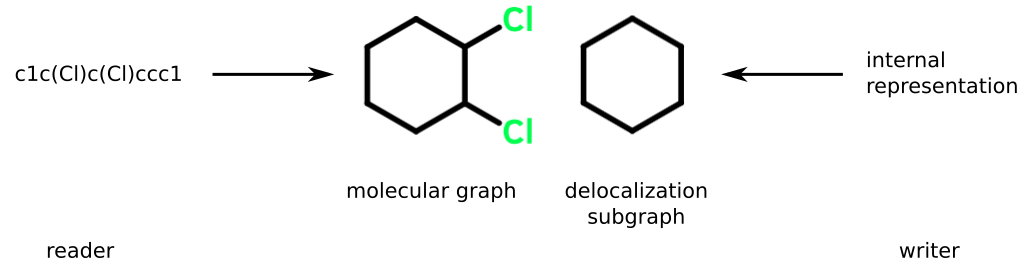

The Delocalization Subgraph

SMILES is fundamentally a system for encoding molecular graphs. As with similar systems, atoms map to nodes and bonds map to edges. It's sometimes convenient to gather a subset of nodes and edges together. Such a collection is called a subgraph.

In addition to a molecular graph, SMILES also supports a subgraph I'll designate as the delocalization subgraph (DS). The delocalization subgraph contains those atoms and bonds that have been identified as "aromatic." This subgraph can be connected or not.

SMILES readers and writers each construct a DS, albeit using different methods and to different ends:

- Reader. Adds atoms and bonds according to the encoding of the tokens found in a SMILES string. The resulting subgraph can then used to transform the molecular graph.

- Writer. Adds atoms and bonds belonging to features in a kekulized molecular graph deemed capable of DIME. Output tokens representing members of the DS are modified according to well-defined rules that will be described shortly.

Aromaticity Syntax

The set of rules whereby aromaticity is encoded within a SMILES string fall under the heading of syntax. These rules have been documented before, but for the most part implicitly and to my knowledge never concisely in one place. The rules of SMILES aromaticity syntax are:

- An atom with a lower case symbol is added to the DS.

- Only atoms associated with the following elements can be added to the DS: C; N; O; P; S; As; Se.

- An elided or aromatic bond between two members of the DS is added to the DS.

Benzene offers a convenient model to explore these rules. Imagine we want to ensure that all atoms and bonds are included in the aromaticity subgraph. The simplest way to do this is to combine lower case symbol (Rule 1) with bond elision (Rule 3):

c1ccccc1

A bond given any explicit designation other than aromatic (:) will not be added to the aromaticity subgraph. For example, we can construct a representation of biphenyl that excludes the bond between the two benzene rings from the DS. The result is a subgraph containing two disconnected cycles of size six:

c1ccccc1-c2ccccc2

The rules of aromatic SMILES syntax are very flexible. For example, we can build a DS for benzene that contains six degree zero nodes and no bonds:

c1-c-c-c-c-c-1

Should such a SMILES be considered valid? To decide we'll need to assign meaning to the aromaticity subgraph.

Kekulization

The most important application of the DS for SMILES readers is kekulization. Kekulization is the process of assigning double bonds to a molecular graph using the DS as a guide. Kekulization occurs before the assignment of virtual hydrogens.

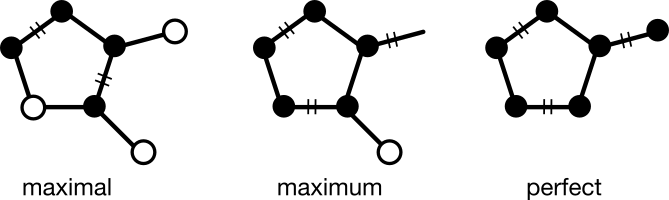

The problem of assigning alternating double bonds is just one instance of a broader problem in graph theory known as matching. A matching is a subgraph in which each node has degree one. Three kinds of matching are of interest: maximal (no additional edges can be added); maximum (all possible edges have been added); and perfect (all nodes have been added). A previous article described the matching problem in detail.

For reasons that will soon become clear, the DS must be pruned before use. Pruning removes those atoms incapable of forming a double bond without introducing a radical or charge. The essential requirement for doing so is the presence of an unpaired electron. Therefore, any atom in the DS without an unpaired electron must be pruned. This can either be accomplished algorithmically or by comparison to a whitelist of atom types. Edges to pruned atoms are themselves pruned as well.

The pruned DS is then processed by a matching function. If a perfect matching is not found, an error is thrown. If a perfect matching is found, the formal bond order of matched bonds in the molecular graph is increased by one.

This approach yields an alternating set of double bonds in every possible situation, including those that most would not consider "aromatic." For example, ethene represented as cc can be kekulized, as can butadiene (cccc). The allyl radical (ccc), however, can not be kekulized because its DS has no perfect matching.

Kekulization works with a single, connected DS. But the nature of graph matching also eliminates any need to split the DS into connected components. Also gone is the requirement to perceive cycles during kekulization because Hückel's rule is not used. The result is a process whose complexity scales with that of the graph matching problem.

An aromatic SMILES that can't be kekulized must yield an error. This sets a necessary and sufficient condition for validity of the DS:

If no perfect matching for the pruned DS exists, the corresponding SMILES is invalid.

Aromatization, Round One

A SMILES writer constructs a DS by identifying those features capable of DIME. This raises the question of how to identify those features.

Weininger leaves something to the imagination here, partly because he conflates the SMILES language with the behavior of his software implementing it. Nevertheless, the following passage offers useful insights:

SMILES algorithms detect accurately the vast majority of aromatic compounds and ions. The system will accept either aromatic or nonaromatic input specifications; it will detect aromaticity and will convert the input structure accordingly. This is accomplished with an extended version of Hückel’s rule to identify aromatic molecules and ions. To qualify as aromatic, all atoms in the ring must be sp2 hybridized and the number of available "excess" π electrons must satisfy Hückel’s 4N+2 criterion.[citation to the author's textbook] As an example, benzene is written clcccccl, but an entry of C1=CC=CC=Cl1(cyclohexatriene) - the Kekulé form - leads to detection of aromaticity and results in an internal structural conversion to aromatic representation. Entries of clcccl and clcccccccl will produce the correct antiaromatic structures for cyclobutadiene and cyclooctatetraene, C1=CC=C1 and C1=CC=CC=CC=Cl, respectively. In such cases the SMILES system looks for a structure that preserves the implied sp2 hybridization, the implied hydrogen count, and the specified formal charge if any. Some inputs, however, may be not only formally incorrect but also nonsensical such as c1cccc1. Here c1cccc1 is not the same as C1=CCC=C1 (which is a valid SMILES for cyclopentadiene) since one of the carbon atoms is sp3 with two attached hydrogens. In such a structure, alternating single- and double-bond assignments cannot be made. The SMILES system will flag this as an "impossible" input.

Summarizing and paraphrasing the salient points, a writer adds all atoms to the DS, except:

- saturated atoms;

- acyclic atoms;

- members of cycles not satisfying Hückel's 4n+2 rule.

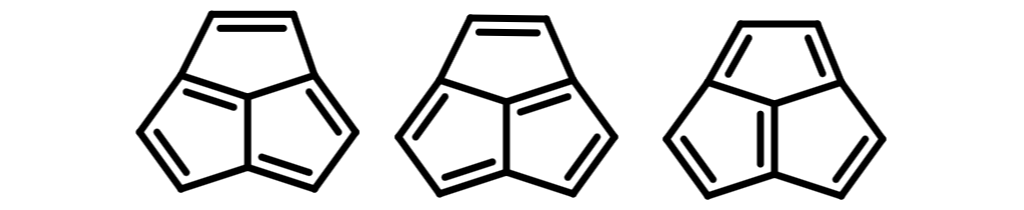

The main problem with this approach is the dependence on Hückel's 4n+2 rule. On the one hand it fails to identify features capable of DIME. Consider acepentalene:

No small ring or outer envelope conforms to Hückel's rule and yet DIME is clearly possible. Many such examples can be found. For example, the closely related pentalene, with eight electrons, doesn't obey Hückel's rule in any formulation and still displays DIME.

Weininger himself notes that the aromatic representation for butadiene (c1ccc1) will kekulized when read, consistent with a graph matching approach. But should butadiene, pentalene, acepentalene, or any of the multitude of ring systems capable of DIME but not obeying Hückel's rule be encoded using aromatic notation? The question is to my knowledge never answered in any of the Daylight documentation. If each SMILES writer must make the determination, why even mention Hückel's rule in the first place?

The problems run deeper still. As noted as early as 1952, Hückel's rule can only be justified computationally for monocycles. Weininger's own description appears to acknowledge this limitation with the phrase "all atoms in the ring [singular]." Nevertheless, the literature of organic chemistry is filled with examples of polycyclic species capable of DIME.

Any specification that couples itself to Hückel's rule can not make good on the promise of addressing DIME. Fortunately, we can do better.

Aromatization, Round Two

Let's approach the problem from a different angle by first asking a question: "What are the essential features for DIME?" Given an answer to this question, we can devise rules that will exclude features giving rise to it. The rule can be stated in terms of graph theory as follows:

DIME can result when a molecular graph contains a single cycle or a system of fused cycles whose pattern of double bonds defines a perfect matching.

The simplest example is benzene. The molecular graph contains one cycle, whose double bonds define a perfect matching over the cycle. Therefore, the benzene ring allows resonance-induced asymmetry and should be represented using aromatic notation.

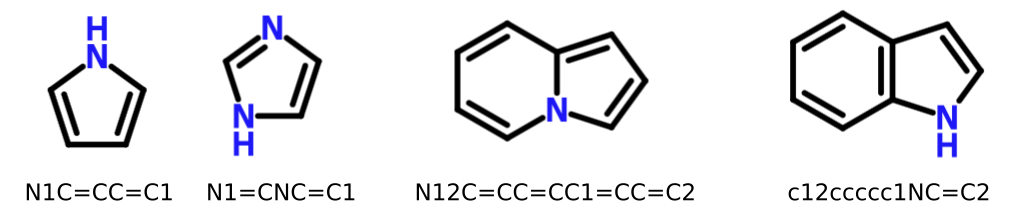

What about pyrrole? Weininger's paper includes it as an example of a molecular graph that can or even should be represented using aromatic SMILES. However, it's plain to see that pyrrole is incapable of producing DIME. No matter how delicately we push electrons, a radical or charge separation must result.

In other words, we can safely represent pyrrole and many other heterocycles in Kekulé form without introducing DIME.

This raises the question of why such heterocycles are so commonly seen in their aromatic SMILES form. One factor is likely convenience. Aromatic notation allows bond elision, which results in fewer characters in the SMILES string. However, it's crucial to recognize that the driving force behind aromatic SMILES is canonicalization. And in that light, many traditional aromatic representations in common use today are superfluous. As Weininger himself notes:

Given effective aromaticity-detection algorithms, it is not necessary to enter any structure as aromatic if the user prefers to enter an aliphatic (Kekulé-like) structure. Entering structures as aromatic provides a shortcut to accurate chemical specification and is closer to the mental molecular model that most chemists use. One advantage of a rigorous algorithmic redefinition is that any valid structure which suits the user can be automatically converted to a standard form.

Fortunately, a reader following the guidelines presented here will be able to kekulize pyrrole and any other heterocycle regardless of whether aromatization was performed out of necessity or convenience.

What about cycle systems? A cycle system is a subgraph created by the fusion smaller cycles. For example, naphthalene contains a cycle system created from the fusion of two benzene rings. Indole contains a cycle system created from the fusion of a benzene ring with a pyrrole ring. Acepentalene contains a cycle system created from the the fusion of three five-membered rings, and so on.

The rule proposed here specifically allows for cycle systems, unlike Hückel's rule. All that's required is that the cycle system contains a pattern of double bonds consistent with a perfect matching over the cycle system. The goal of an aromatization algorithm should be to find such cycle systems.

Aromatization Algorithm

It should be clear by now that aromatic SMILES notation is an optional feature not strictly required in any situation. Canonicalization is difficult, but not impossible without it. Any bond or atom, aromatic or not, can be added to the DS provided that a perfect matching can be found for the pruned result. It will likely be a design error to rely on externally-generated aromatic SMILES notation to accelerate any chemical computation. Even then, the purpose for writing aromatic SMILES should be to avoid DIME. Convenience might be another goal.

Given a writer capable of canonicalization using aromatic SMILES, our goal is to find cyclic molecular features whose pattern of double bonds supports a perfect matching. For example, a benzene ring qualifies. So do naphthalene and acepentalene. Pyrrole, imidazole, and any cycle system without a perfect matching don't qualify. More broadly, we also consider cycle systems, a group of simpler cycles fused together.

The first version of this article described a procedure for populating the DS based on the set of relevant cycles, the union of all minimum cycle bases. This cycle set is, however, unsuitable for the task. For a procedure that can work, see the follow-up article Writing Aromatic SMILES.

Related Work & Acknowledgements

For many years, Weininger's papers and Daylight's online articles were the only written documentation for the SMILES language. Useful though they were, several limitations prevented these materials from serving as the basis for standardization.

Starting in 2007, a group of scientists including myself met online through a mailing list to discuss ways to improve SMILES documentation. The result was the OpenSMILES specification. As noted on the home page, the goal of our effort was to fill in some of the missing pieces, not create something new.

At this point in the history of SMILES, it is appropriate for the chemistry community to develop a new, non-proprietary specification for the SMILES language. Daylight’s SMILES Theory Manual has long been the "gold standard" for the SMILES language, but as a proprietary specification, it limits the universal adoption of SMILES, and has no mechanism for contributions from the chemistry community. We salute Daylight for their past contributions, and the excellent SMILES documentation they provided free of charge for the past two decades.

Aromaticity was one of the most-discussed topics among the OpenSMILES group. Motivated by these discussions, I posted an article here. Shortly after that, Andrew Dalke, also part of the OpenSMILES group, posted a detailed response.

John May's 2015 dissertation addressed many of the topics covered here in Chapter 5.

In 2016, the topic of aromaticity in SMILES resurfaced on the OpenSMILES mailing list. An important outcome of that discussion was to update Section 3.5.3 of the OpenSMILES specification with the π-electron contribution table that now appears there.

In 2017 Noel O'Boyle picked up the topic again with an ACS talk, an article, and some online discussion. In 2018 he again returned to the topic of aromaticity in SMILES, this time in the context of a benchmarking initiative.

In 2019 IUPAC announced the creation of SMILES+, an effort with the goal of formalizing a community-developed, living SMILES specification. To date, the SMILES+ working draft consists of an almost verbatim copy of the OpenSMILES specification. A recent ACS presentation lists resolution of the aromaticity question as an important topic.

More recently, the topic of aromaticity in SMILES resurfaced again as an RDKit issue. The molecule in question was acepentalene.

I've drawn from all of these documents and discussion to develop the proposal here.

Implementation

The ideas presented here are being incorporated into the ChemWriter, my company's structure editor and rendering package. A test page is available, and will be updated as progress is made.

Conclusion

Aromaticity has consistently proven be one of the most difficult SMILES features to understand and standardize. The original intent of aromaticity was to avoid artificial asymmetry induced by resonance, and thereby allow SMILES to be used as a canonical molecular representation. From this perspective, Hückel's rule is provably unsuited to the task. An alternative approach based on graph theory — specifically perfect matching — is proposed. Detailed guidelines for both readers and writers should make this approach available to all cheminformatics toolkits.