A Dedicated Library for Reading and Writing V3000 CTfiles

The CTfile specification defines a suite of popular cheminformatics serialization formats including SDfile, Molfile, and RGfile. CTfile currently comes in two varieties: V2000 and its successor, V3000 (aka "V3K"). V3K may not be as widely-used as its older sibling, but many of its features are unique. Even so, V3K is at least as complex as what came before. Chalk this up to pairing those new features with partial backward compatibility.

The task of reducing the CTfile specification to software typically falls to a monolithic cheminformatics toolkit such as RDKit, CDK, Open Babel, or various commercial alternatives. But this isn't the only way. This article outlines an alternative approach being used for a work in progress.

Goals

For the time being I call the project "Vek." It has four main goals:

- Fidelity. Vek should read and write all representations permitted by the V3K specification. Conversely, Vek should reject any representation disallowed by the V3K specification.

- Portability. Vek should run on any operating system and on any meta-platform such as a Web browser.

- Speed. Vek should be fast enough that it is not a performance bottleneck for downstream uses.

- Flexibility. The data structures and functions exposed by Vek should be readily usable in a variety of contexts.

Language

After considering several alternatives, Rust was chosen as the implementation language. A previous article explained some of what Rust has to offer specifically for cheminformatics. Rust's features dovetail well with the four goals outlined above. Speed and memory efficiency are two things Rust is known for (Goal 3). Less known is the broad range of platforms Rust can be compiled to, or the many ways in which Rust can be integrated with software written in other languages (Goals 2 and 4). Previous articles here have noted how Rust can be compiled to WebAssembly and called from Python, for example.

Some of Rust's best features only become clear through extended use. Rust's type system in particular will play an important role in enabling Goal 1.

Implementation

Vek's initial development focused on data types. Two principles guided their design:

- It should be impossible to construct an invalid representation using safe Rust.

- Any value held in memory can be assumed to be valid.

To the greatest practical extent, Vek replaces runtime validity checks with compile time checks. Rather than a "defensive programming" approach in which all data are suspect until proven otherwise, Vek makes it possible to use values safely without performing these checks. To be more specific, these checks are performed at compile time, not run time. This approach has been elegantly described by Alexis King in his essay Parse, don't validate.

Consider Vek's central abstraction, ConnectionTable. This type represents the concept of a "connection table" found in the specification.

pub struct ConnectionTable {

pub atoms: Vec<Atom>,

pub bonds: Vec<Bond>,

// Used by "enhanced stereochemistry" and extensions.

pub collections: Vec<Collection>,

// Shortcuts such as "Ph", "Et", etc.

pub substructures: Vec<Substructure>,

}

ConnectionTable holds collections of other values. The first one listed, atoms, represents an ordered list of zero or more atoms. The Atom type is defined as follows.

pub struct Atom {

pub index: Index,

pub kind: AtomKind,

pub charge: Charge,

pub coordinate: Coordinate,

pub atom_atom_mapping: Option<Index>,

pub valence: Option<usize>,

pub mass: Option<usize>,

pub attachment_point: Option<AttachmentPoint>,

}

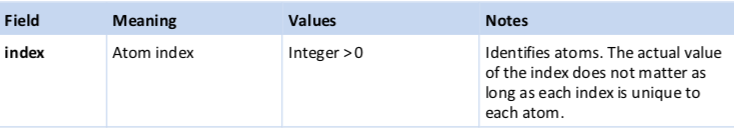

Atom is itself composed of multiple values. The topmost attribute is index, which is a unique numerical identifier. The V3K specification has the following to say about atomic identifiers:

Here it's helpful to distinguish semantic from syntactic validity. The syntactic part of the description of index is "Integer > 0." The semantic part is "unique to each atom." Data structures can guarantee syntactic, but not necessarily semantic validity. Similar considerations apply to the implicit semantic guarantee that bonds reference atomic indexes actually associated with atoms.

pub struct Index(String);

To improve type safety Index uses Rust's newtype idiom, wrapping a private Rust String value. The use of a String makes it possible to support arbitrarily large values for Index as required by the specification.

The String value associated with Index is private, meaning that Index can't be constructed using literal notation. Instead, associated functions transform other types into Index. Each function checks the values its given, reject those that can't be transformed into a valid Index. For example, a constructor transforms a usize argument, checking that its value is not zero. The return type is Option<Index>, forcing the caller to handle the possibility that a zero value was passed and the None variant was received. At no point is it possible to construct an Index representing the integer 0.

impl Index {

pub fn new(value: usize) -> Option<Index> {

match value {

0 => None,

_ => Some(Index(value.to_string()))

}

}

}

A better illustration of the "parse, don't validate" approach is the AtomKind type, a member of Atom.

pub enum AtomKind {

Element(Element), // C, N, O, P, S, Pd, etc.

Rgroup(IndexList), // References an Rgroup in an RGfile

ElementList(ElementList), // possibly negated list of elements

PolymerBead, // usually depicted as shaded sphere

Any, // no information available

}

AtomKind is an enumeration. Although many languages have enumerations, Rust lavishes syntax and tooling on them that few languages can match. The variants of AtomKind can be divided into two categories: those with their own associated types (Element, Rgroup, and ElementList), and those without (PolymerBead and Any). The former group supports variants having unique, mutually exclusive data and behaviors. This idea goes by the general term algebraic data types.

Algebraic types make it easy to model mutually-exclusive data types. For example, the AtomKind::Element and AtomKind::Rgroup variants have little in common. The former is an enumeration of the chemical elements, whereas the latter is an ordered list of Rgroup indexes. Both cases are supported without cross-contamination of data.

pub enum Element {

H,

He,

Li,

// etc.

}

pub struct IndexList(Vec<Index>);

Consider how difficult it would be to model this kind of relationship without algebraic data types. Every field supported by Atom would need to be present on Atom itself. An Atom would need to define both element and index_list, without any way to ensure their mutual exclusivity. The behavior of a function receiving an Atom in which both fields were set (or neither was) would need to be defined outside the scope of executable code. Rust solves this problem by providing the tools needed to make invalid states uncompilable in the first place.

Data First

There aren't many examples of dedicated serialization libraries in cheminformatics. Most read/write functionality is instead tightly coupled to a specific toolkit. In fact, I only know of two standalone projects in this area that are under active development:

- Beam. SMILES reader and writer.

- Dialect reference implementation. Reader and writer for a subset of SMILES called Dialect.

Writing software that distills industry-standard specifications such as V3K down to practice can extremely challenging. The specifications themselves can be ambiguous or self-contradictory. Their features may not mesh well with the limitations of a given programming language. It's the kind of thing you might want to do once and reuse often. This isn't always possible when serialization is tightly-coupled to a general-purpose cheminformatics toolkit.

There's also something more subtle. Serialization and deserialization require a backing store, or in-memory representation. Perfect alignment with a given serialization format can rarely be achieved due to the common requirement to support two or more of them. Mismatch between representations can cause data to be lost or corrupted. For example, aromaticity is a nuanced property that no two representations handle the same way. Expanding the toolkit's API surface to accomodate these difference can lead to bloat and performance bottlenecks. Lightweight abstractions, such as a minimal molecule API, become much less practical. Loose coupling allows toolkit and serialization format to evolve independently.

Finally, there are times when a cheminformatics toolkit is overkill or too restrictive for the task at hand. For example, maybe the goal is to simply validate a large input file, or rewrite it to meet organizational conventions. These are the kinds of lightweight task at which Vek would excel.

Should the need arise, Vek can be integrated into a cheminformatics toolkit through Rust's Cargo package manager. All the toolkit would require is a lightweight bridge between its backing store and Vek's data structures.

Conclusions

Vek is a standalone implementation of the V3000 CTfile specification. When complete, it will expose data structures and functions capable of high-fidelity reads and writes. Rust was chosen as the implementation language to provide the best possible combination of fidelity, portability, speed, and flexibility. Work on V3K is currently underway as part of a commercial ChemDraw CDXML/V3000 translation utility. In the near future I plan to release the first iteration of V3K under an open source license.