TUCAN Canonicalization Revisited

Molecular identifiers, also known as "chemical names," underpin modern chemistry. A recent paper introduced TUCAN, a new molecular identifier. As noted in my overview, TUCAN could one day play a similar role in molecular identification as canonical SMILES and IUPAC nomenclature. An important point along the way is canonicalization, or the selection of one representation out of many possible for a given molecule. This article approaches the topic of TUCAN canonicalization from first principles, distinguishing required from optional steps.

TUCAN Syntax

It might seem odd to start a discussion of canonicalization with syntax. After all, isn't canonicalization just the reproducible assignment of indexes to the nodes of a graph? Yes and no. As we'll see, the syntax used by string representations can be exploited during canonicalization as an integral component of algorithm development. If nothing else syntax can constrain index assignment and so must be considered prior to canonicalization.

A TUCAN string consists of two components, a formula and an ordered bond list. The syntax can be generalized as the template {formula}{bonds}. The formula component is expressed using Hill Notation. This notation lists an atom's elements starting with first carbon then hydrogen. The remaining elements are listed in alphabetical order. A numerical count follows each element if it exceeds one. If an element is not present, it is omitted from the the formula. An element symbol only appears once. For example, the Hill Formula for glucose is "C6H12O6." The bond list is a concatenation of individual bond representations. A bond is represented by the template /{source}-{target}, where {source} is the bond's source index and {target} is the bond's target index.

TUCAN imposes three additional constraints on syntax:

- Atoms must be indexed in order of ascending atomic number.

- A bond's target index must succeed its source index. In other words, a bond between atoms 5 and 3 must be written as "/3-5" and must not be written as "/5-3".

- The bond list must be sorted in increasing numerical order. That order is determined by the value of the source index followed by the value of the target index. For example, the correct order for two bonds, one between atoms 7 and 3 and the other between atoms 4 and 3 is "/3-4/3-7".

A bond list can more generally be represented with tuple notation. This method represents bonds by their numerical indexes wrapped in parentheses and separated by a comma. For example, the bond list representations "/3-4/3-7" and (3,4)(3,7) are equivalent.

The Simplest Canonicalization Algorithm

The simplest canonicalization algorithm consists of generating all possible representations and choosing the lexically minimal (or maximal) one. This procedure can be performed on a string, but also many other kinds representation. In TUCAN, the formula component does not change with atom indexing, so it can be disregarded for the purpose of canonicalization. This leaves just the bond list as a point of variation.

Identifying the lexically minimal representation requires an order over them. Given two members of a set, an order makes it possible to determine which is greater or lesser. This information can be encapsulated by an operation called compare that accepts two set members and returns one of three values depending on whether the first input is greater than, less than, or equal to the second. The compare operation lays the foundation for algorithms that can sort the members of a collection, and determine its minimal and maximal values.

TUCAN's syntax provides a ready-made definition for the compare operation. If the source index of the first bond precedes the source index of the second bond, the first bond precedes the second. If both source indexes are equal, the first bond precedes the second bond if its target index precedes that of the second. Otherwise the two bonds are equal to each other. This simple compare procedure sorts the bonds within a single molecule from minimal to maximal. It can also be used to compare bond lists.

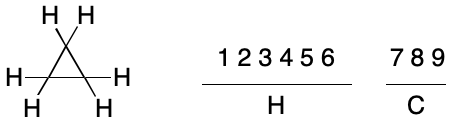

Given a method to compare TUCAN representations, how many need to be considered? A molecular graph of n atoms can be indexed in n! different ways. TUCAN does not support hydrogen suppression, so every hydrogen atom must be represented as a node, which can drastically increase the value of n. For example, cyclopropane contains 9 atoms (3 carbons and 6 hydrogens). In general, there are 9! (362,880) different ways to index the atoms, ignoring symmetry. In practice, both symmetry and the syntax of an identifier limit the number of unique indexing permutations.

TUCAN's syntax constrains the number of representations that need to be considered in two ways: (1) by limiting the indexes assignable to an atom; and (2) by sorting the bond list in ascending order. The next section explores the consequences of (1) in detail. Near the conclusion, we'll return to (2).

Invariants and Automorphism

TUCAN's requirement for atoms to be indexed by increasing atomic number is an example of an atomic invariant. An atomic invariant is a value computed on an atom that doesn't change when indexing changes. Numerous atomic invariants have been developed, and some are described in the TUCAN paper. For example, degree (neighbor count) is an atomic invariant, as is distance sum (the sum of shortest path lengths from a given atom to every other atom).

The application of an invariant to the atoms of a molecular graph results in one or more atom invariant classes ("invariant classes", aka "partitions"). Partitioning atoms among two or more invariant classes is useful because it reduces the number of possible indexings. For example, a single invariant class for the atoms of cyclopropane leads to 9! (362,880) possible indexings in the general case. However, partitioning atoms by atomic number leads to two invariant classes: one containing six atoms and the other three. The number of possible indexings is reduced to 6!*3!, or 4,320.

This set reduction traces its origins to the concept of automorphism. Automorphism is an isomorphism applied not between two different graphs, but between the same graph with two different indexings. The concept is closely related to molecular symmetry. When a symmetry operation can interconvert two nodes, they are automorphic. For example, the hydrogen atoms in cyclopropane are automorphic with each other, as are the carbon atoms. The atoms within each invariant class happen to be related by symmetry operations in this example and are therefore automorphic. By comparison, no atom will ever be automorphic with any atom outside of its invariant class. Carbon and hydrogen atoms can't map to each other under any symmetry operation.

In practical terms, the atomic number invariant drastically reduces the number of unique indexings for cyclopropane from 9! (362,880) to 6!*3! (4,320). This nearly 100-fold reduction raises the question how to achieve further reductions. It's tempting at this point to generalize from specific examples, but that would be a mistake.

No Free Lunch

Atoms drawn from different partitions will never be automorphic. However, atoms drawn from the same partition may or may not be automorphic. Whether or not they are depends not only on the invariant but the graph itself.

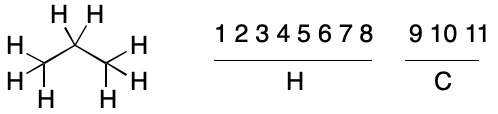

Consider propane. Application of the atomic number invariant leads to two invariant classes, one with eight hydrogens and the other with three carbons. Recall that we saw something similar with cyclopropane. As before, the hydrogens can never be automorphic with the carbons. However, some hydrogens are automorphic with certain hydrogens, but not others. The same applies to the carbons.

Without proof, no atomic invariant can be assumed to have perfect discriminatory power. In other words, no atom within a partition can be assumed to be automorphic with any other member of the same partition. For the purpose of assigning a canonical string, the atoms within a partition must be treated as if they were not related by symmetry.

This point bears repeating. No atom within a partition, regardless of how elaborate or compelling the invariant that gave rise to it may appear, can be assumed to be automorphic with its cohorts. The atoms within a partition must be assumed to be non-automorphic until proven otherwise.

Every canonicalization algorithm, no matter how revolutionary its atomic invariant is portrayed, must include a step in which the atoms within a partition are exhaustively permuted. That step can be made less expensive by, for example, devising more sensitive invariants thereby minimizing the size of each partition. But the permutation step can not be eliminated. Nor should the efficiency of any canonicalization algorithm be judged without accounting for the cost of permutation.

In his review of molecular canonicalization, Ivanciuc calls this step canonical code generation by automorphism permutation (CCAP). For an illustrated introduction to this review, see my summary of it from last year. Many of the terms and concepts developed by Ivanciuc have been adapted for use here. For convenience the terms "CCAP" and "permutation" will be used interchangeably.

Unfortunately, several published canonicalization schemes fail to account for this point. As noted in a paper by Kroto:

Since both published by Weininger et al. and by Schneider, Sayle, and Landrum algorithms for canonicalizing of SMILES do not contain CCAP (canonical code generation by automorphism permutation) step, they are incomplete, i.e. for some molecular graphs they could give different canonical SMILES for the label permutations of one molecular graph. …

For its part the paper in question by Schneider and coworkers admits the lack of a CCAP step while attempting to justify it:

To rigorously prove that the atoms within one equivalence class [i.e., partition] obtained after the refinement phase are symmetry equivalent, which would make it valid to use our tie breaking procedure, a systematic test by renumbering using all permutations within the equivalence class would be required. More sophisticated approaches to this rather time-consuming brute-force process have been proposed in the literature. These include the use of generating sets — allowing many of the permutations to be skipped — and a combination of backtracking and comparison of candidate adjacency matrices to prune the backtracking tree. Since the use of appropriate atom invariants removes the need for this elaborate step in the canonicalization of almost all kinds of chemical graphs, we decided to not include it in our novel approach. [my emphasis] We believe that the successful results from the extensive renumbering and round-tripping tests on a large set of diverse molecules as well as on very symmetrical graphs demonstrate the robustness of our new method.

From my reading, the Schneider paper offers no proof of perfect discriminatory power for the atomic invariant it presents. Nevertheless the algorithm explicitly excludes a permutation step. As such, the claim of a broadly-applicable canonicalization scheme, and the benchmarks presented for it, should be viewed with skepticism.

Example Permutation

A valid canonicalization of TUCAN strings requires a permutation (CCAP) step, regardless of the partitioning performed prior to it. What this means in the worst case is that the atoms in each partition are exhaustively reindexed and permuted with the others.

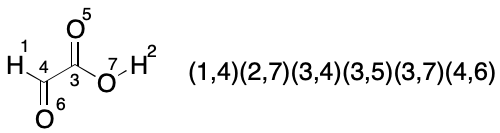

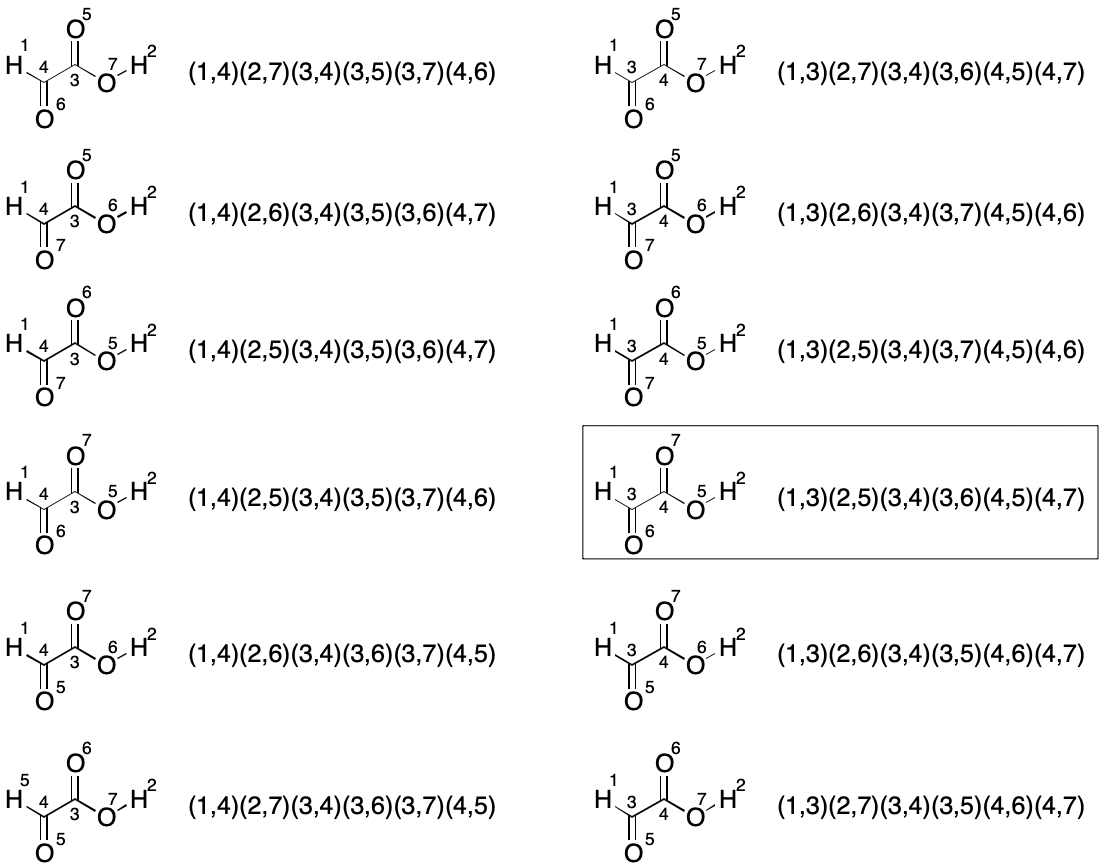

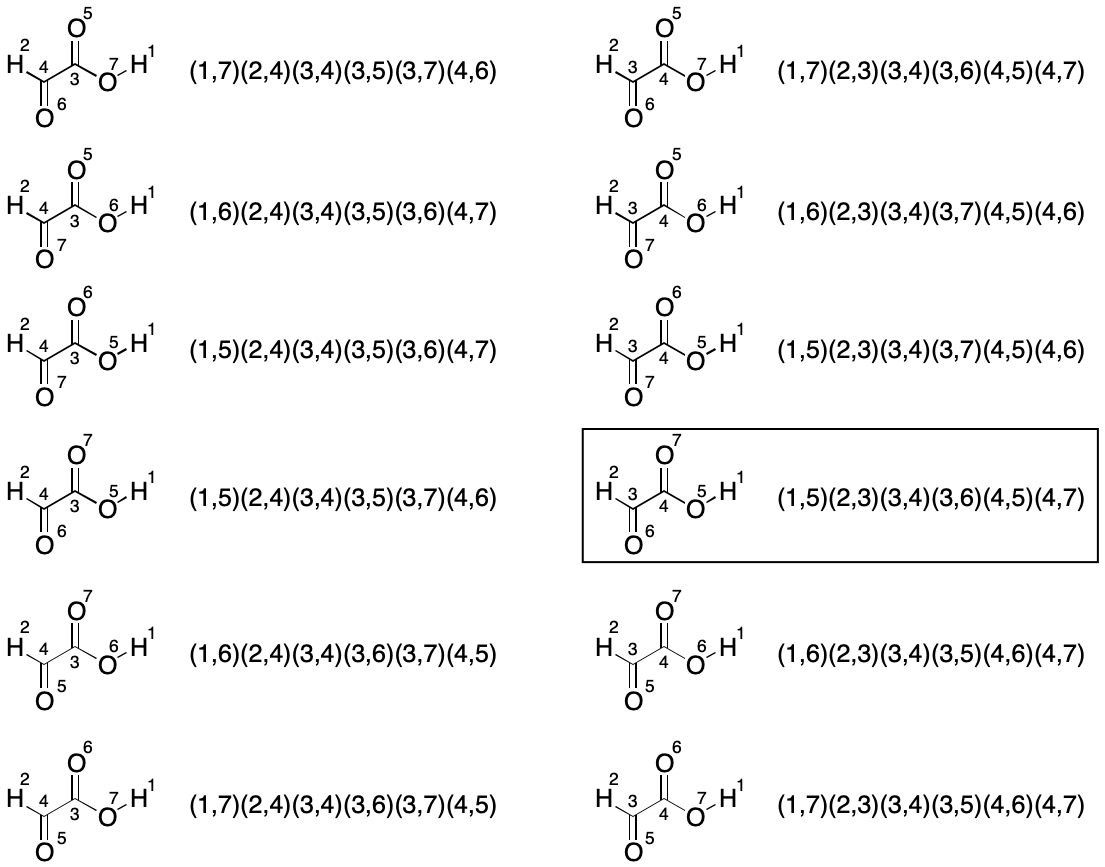

Consider glyoxylic acid. Its seven atoms are split into three partitions by TUCAN's atomic number invariant. The count of atoms in each partition is hydrogen (2), carbon (2) and oxygen (3). Assuming no further partitioning (the worst case), which indexings must be considered? We know there will be 2!*2!*3!, or 24 of them, but what are they and how can they be enumerated?

We start with a random indexing consistent with TUCAN syntax. The goal is to enumerate the 23 remaining indexings for a full set. One approach is to fix the indexes of one partition, then exhaustively permute the indexes of the remaining two partitions until all indexings have been enumerated.

The first set of twelve permutations is obtained by fixing the members of the hydrogen partition and permuting the members of the remaining two partitions, yielding a total of 2!*3! (12) indexings.

The next set of twelve permutations is obtained by swapping the hydrogen atom indexes (1 and 2) and permuting the remaining two partitions again for a total for 12 new indexings.

This brute-force analysis reveals the lexically minimal string to be "C2H2O3/1-3/2-5/3-4/3-6/4-5/4-7".

Algorithm

Given small numbers of partitions with few atoms in each one, it's a simple matter to generate all permutations. But doing the same thing in the general sense with larger molecules is a different matter. What's needed for this step is an efficient method for generating permutations. This is, perhaps surprisingly, a non-trivial problem. What we're after is an algorithm that works with O(n!) time complexity. In other words, the algorithm should not enumerate anything it doesn't have to. Such algorithms have been reported, perhaps the best-known of which is Heap's Algorithm.

Based on Heap's Algorithm or something similar, the full set of TUCAN indexings for any molecule can be enumerated. There would be a clear recursive element to such an algorithm in that permutations within one partition would themselves be permuted with permutations within the remaining partitions.

But such an algorithm, although rigorously correct, would be hopelessly impractical given its factorial complexity. What tools might be deployed to increase efficiency?

We Can Do Better

Two powerful approaches are available when devising canonicalization algorithms: (1) minimizing the size of partitions; and (2) exploiting the syntax of strings. Each offers its own palette of tools.

Simple math and the glyoxylic acid example reveal that the size of the largest partition governs efficiency. A plethora of methods are available for expelling heteromorphic atoms from a partition. For example, atoms can be further partitioned based on their degree. Taking just this one step with glyoxylic acid reduces the number of permutations from 24 to 8 (2!*2!*2!\1!).

TUCAN's syntax can also be exploited. Recall that the bond list is sorted. One consequence is that a permutation can only be minimal if its first bond is minimal. Looking back at the glyoxylic acid example, the minimal bond is (1,3). Rather than the random permutation in the example, a directed permutation could be used. We'd start by forming the first minimal bond (1,3), then forming the next available minimal bond, and so on. In this manner search space can be organized into a tree.

In some cases, it wouldn't be clear what the next bond should be. If so, we'd try one branch and see where it led. Then we'd backtrack to try the next branch, and so on. If a branch clearly could not result in a minimal permutation, it could be dropped, saving the time it would have taken to fully traverse the branch. In this way, the search space could be pruned without decreasing the rigor of the approach.

Given that permutation (CCAP) is an unavoidable and potentially expensive step, time spent in optimization here would be well-rewarded.

Conclusion

Although often described in very complex terms, canonicalization is not a conceptually complex process. Given some order of atomic indexings for a given molecule, we select the minimal (or maximal) one as the canonical form. The search space is factorial in size. Atomic invariant partitioning offers a powerful method for reducing search space. But because no invariant is perfectly discriminating, a second exhaustive permutation step will always be required. Fortunately, this step too can be made more efficient through careful consideration of the constraints imposed by syntax.

Note

This article supersedes the one published earlier. That previous attempt to explain TUCAN canonicalization failed on several levels. It is nevertheless being preserved to highlight some of the pitfalls faced when developing canonicalization procedures.