Molecular Identification with TUCAN

It's hard to overstate the importance of molecular identifiers to chemistry. Also called "chemical names," molecular identifiers enable individuals, laboratories, organizations, and countries to efficiently exchange information about molecules. Given this foundational role, you might expect to find a well-organized and lavishly-funded effort to develop and improve molecular identifiers. This is, of course, not the case. So when a paper comes along that proposes a fundamentally new way of approaching the problem it's worth taking a look.

TUCAN

A recent preprint describes a new molecular identifier called TUCAN ("tuple canonicalization"). Like InChI, systematic nomenclature, and canonical SMILES, TUCAN identifiers (or "strings") can be generated without a centralized service. I call this approach "algorithmic identification." Algorithmic identifiers offer an attractive alternative to CAS Numbers, which bear the costs of a centralized service and the counterproductive business practices it engages in. InChI, canonical SMILES, and systematic nomenclature work well when restricted to the kind of molecules covered in a sophomore organic chemistry class. But extending these identifiers to inorganic and organometallic molecules yields mixed results at best. The InChI project, for example, has hosted a working group on organometallics since 2009 that has to date produced no recommendation.

TUCAN aims to solve this problem with a unique identifier that can be applied uniformly well to organic, inorganic, and organometallic molecules. Unlike InChI (but like systematic nomenclature and SMILES), TUCAN strings are designed to be both read and written.

Molecular Graph

Like all algorithmic identifiers, TUCAN is based on an underlying molecular graph. A molecular graph is a graph-like data structure whose nodes and edges are labeled with chemically-relevant metadata. The molecular graph used by TUCAN is extremely simple in that it associates just one piece of chemical metadata at each node: the atomic number.

TUCAN's graph notation omits several features that will prevent its immediate adoption. For one, constitution is incompletely defined. A neutral molecule and its ion can not be distinguished, for example, due to the lack of electron counting. Also missing is support for isotopic composition, conformation, and configuration. The authors note that these missing features will be "the topic of a separate follow-up publication." These might be retrofitted using a layered approach like the one found in InChI.

Another point of departure with TUCAN is the rejection of hydrogen suppression. Each hydrogen atom, without exception, exists as a full node. Hydrogen suppression is is common in other molecular representation systems as a data compression technique. Its omission from TUCAN does not limit the range of accessible molecules, but will lead to reduced information density.

Serialization

Algorithmic molecular identifiers such as TUCAN require a method for serialization. Serialization transforms a molecular graph into a form that can be conveyed using commodity technologies. Strings are ideal for this purpose and this is what TUCAN uses as well. However, the manner in which TUCAN strings are encoded is somewhat unusual.

A TUCAN string is encoded through the concatenation of two encodings: an empirical formula and an edge list. The result allows the unambiguous association of every node with an elemental symbol.

The empirical formula is encoded using Hill Notation. Carbon (if present) and its count if greater than one appears first. This is followed by hydrogen (if present) and its count if greater than one. The remaining element symbols and their counts (if greater than one) are then concatenated in lexicographical order. For example, the Hill formula for titanocene dichloride is "C10H10Cl2Ti".

The edge list in a TUCAN string does double-duty by providing indexes into the Hill formula to reveal the corresponding element and by revealing node connectivity. This dual purpose requires some preparation. Each node is assigned a one-based integer index in order of increasing atomic number. In other words, hydrogen-bearing nodes receive the first set of indexes, followed by helium-bearing nodes, followed by lithium-bearing nodes, and so on.

Given a valid node indexing, an edge list is compiled. This list is comprised of member tuples, representing edges, which are comprised of the indexes of the terminal nodes. Edge tuples are themselves sorted lexicographically with the lower index appearing first. For example, an edge between nodes 10 and 5 would be represented by the tuple (5,10), not (10,5). Edge tuples are then added to the list in increasing lexicographical order. For example, the set of edge tuples {(2,3),(1,3),(1,4)} would be listed as [(1,3),(1,4),(2,3)].

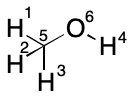

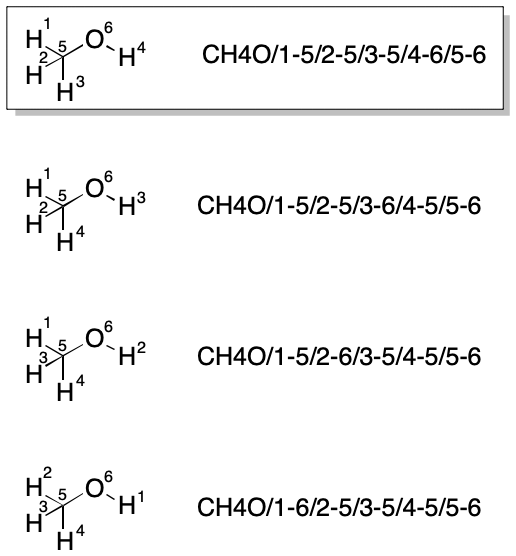

A TUCAN string is encoded by appending the edge list encoding to the Hill formula. The edge list is written by prefixing each entry with a forward slash character (/) followed by the first tuple index, a dash character (-) and finally the second tuple index. For example, a string representation for methanol is "CH4O/1-5/2-5/3-5/4-6/5-6".

TUCAN's string encoding has the interesting property of restricting the number of possible strings. For example, the carbon atom in methanol must always be indexed as 5. Likewise, the oxygen atom must always be given the index 6. Within these restrictions, a given hydrogen can assume the indexes 1-4. In particular, the hydroxyl hydrogen can assume any of the indexes 1, 2, 3, or 4. Each of these assignments leads to a different string. Nevertheless, the number of possible strings is less than it would be without the constraint.

TUCAN explicitly supports deserialization, or the transformation of a string into the graph that produced it. The edge list enables reconstruction of the graph's connectivity. The Hill formula allows atomic numbers to be assigned to the graph. These assignments occur in blocks of increasing atomic number. The Hill formula for methanol ("CH4O"), reveals that indexes 1-4 will be hydrogen atoms, index 5 will be carbon, and index 6 will be oxygen.

Canonicalization

Unique molecular identifiers require a canonicalization algorithm to choose one string representation among two or more possibilities. An earlier article discussed molecular graph canonicalization at a high level. TUCAN follows the pattern described there rather closely.

Canonicalization algorithms represent a tradeoff between computational simplicity and speed. Generally, the simpler the procedure, the slower it will be. For example, the simplest possible canonicalization for TUCAN would be to select the lexicographically smallest valid string. This brute force approach requires the combinatorial enumeration of each string, a simple procedure. Choosing the lexicographically smallest string is even simpler. The problem with the brute force approach is that some molecular graphs will yield large numbers of valid strings and would therefore demand a lot of time and computational cycles for iteration.

This problem is usually addressed through the use of graph invariants, a method used by TUCAN as well. A graph invariant is a property that does not change as nodes are renumbered. For example, the degree (or neighbor count) of a node is an invariant in that it does not change when nodes are reindexed. Likewise, the sum of neighbor degrees is also an invariant.

Invariants are useful because they allow for partitioning. Partitioning is the process of distinguishing previously-indistinguishable nodes based on an invariant. For example, we might partition the nodes in a molecular graph by degree, placing some nodes into a group designated for singly-connected nodes, others into a group designated for doubly-connected nodes, and so on. We can then assign indexing priority to each group. As noted in the previous section, TUCAN's serialization method already partitions and ranks nodes by element. Further partitioning is possible through invariants such as degree and cycle membership. TUCAN uses both.

Partitioning ideally leads to groups whose membership is just one. In such cases, a canonical string can be generated without resorting to brute force enumeration. Despite much effort in this area, no graph partitioning algorithm has perfect discriminatory power. But before resorting to brute force, TUCAN uses one more trick: the one-dimensional Weisfeiler-Lehman algorithm ("1-D WL"). This algorithm resembles the procedure used for generating Penny Codes. In a nutshell, 1-D WL sums connectivity at progressively higher distances from a central node until a stable partitioning is obtained. Presumably, this algorithm has been modified to preserve the atomic number ordering. The paper does not discuss the importance of applying the cycle membership invariant, nor whether 1-D WL by itself would suffice.

Conclusion

Molecular identifiers are a crucial yet largely invisible enabling technology in chemistry. All molecular identifiers developed to date suffer from important limitations, posing a clear challenge. Although TUCAN's restricted feature set might not make it a candidate for immediate adoption, it presents several ideas worthy of consideration in future efforts.