TUCAN Canonicalization

Note: This article requires revisions on one or more important points. In particular, the algorithm does not in its current form enumerate every candidate indexing as claimed. See the revised article for details.

Molecular identifiers (or "chemical names") are everywhere in chemistry. A recent post discussed a new kind of molecular identifier called TUCAN. Serialization was discussed there in some detail, but canonicalization was only outlined. This post picks up where the previous one left off. But rather than discuss the published canonicalization algorithm, this post starts from first principals with a simple, if naive, approach that should work for any molecular graph.

Canonicalization Overview

Graph canonicalization has been covered at length in a review by Ivanciuc. More recently, I summarized this review. The following description contains elements of both works.

The serialization rules for TUCAN covered in the previous post enable every TUCAN graph to be represented as a string (aka "code"). Without any other constraints, however, a TUCAN string generally varies depending on atom indexing. This conflicts with the goal of molecular naming, which requires a string that's invariant with respect to indexing. Such a string is the "canonical" form.

Using TUCAN as a molecular identifier requires both a definition of the canonical form, and the specification of an algorithm to obtain it. A simple approach is to define the lexicographically smallest (or largest) TUCAN string as the canonical form. To obtain it, we simply iterate over all possible strings for a given molecular graph.

Ivanciuc refers to this brute force enumeration step as canonical code generation by automorphism permutation (CCAP). Generally speaking, if a molecular graph has n atoms there are n! possible permutations, each producing its own string candidate. This extremely poor scalability has led to many innovative shortcuts over the last several decades.

All of the approaches to this problem involve graph invariant atom partitioning (GIAP). This step occurs prior to CCAP with the goal reducing the number of string permutations to consider. As hinted previously, an invariant is a property that's constant with respect to re-indexing. Examples include node degree (neighbor count) and atomic number. If successful, the GIAP step partitions a graph's nodes into two or more groups. This partitioning can improve the otherwise factorial scaling of the CCAP step. However, there are two kinds of limits to what GIAP can do. First, no partitioning scheme is perfect. Some constitutionally-distinguishable nodes will nevertheless fail to be partitioned. Second, symmetry imposes a theoretical limit on partitioning. Some groups will have multiple members regardless of the quality of the GIAP protocol.

To recap, canonicalization is a two-step process:

- GIAP, which partitions nodes according to graph invariant heuristics.

- CCAP, which uses the partitions found by GIAP to reduces then number of enumerations that need to be considered. This ultimately leads to the canonical form.

Ivanciuc notes several literature examples in which the subsequent CCAP enumeration step was erroneously thought to be unnecessary. Although molecular canonicalization is possible without GIAP, it is not reliable without a robust CCAP procedure.

The algorithm described here uses only the partitioning enforced by the TUCAN serialization rules. Its goal is to arrive a new atom indexing that can be written as the canonical TUCAN string. The overall approach is to consider the exhaustive, ordered, pairwise exchange of indexes.

Default Partitioning

TUCAN uses an unusual serialization format in which atoms have already been subjected to a limited form of GIAP. To recap, atoms are partitioned by increasing atomic number. Hydrogen comes first, followed by helium, lithium, beryllium, and so on. A TUCAN string consists of a Hill formula followed by a sorted edge enumeration. Each edge within the enumeration is configured with the lowest index appearing first. The result is a string that's already undergone a lot of useful processing. TUCAN strings can be read to re-generate the corresponding molecular graph.

This is the starting point for the algorithm outline that follows. Although it should in principle be possible to apply additional GIAP partitioning heuristics, these will not be considered at this time. This should enable baseline performance metrics to be obtained which could then be used to develop better partitioning methods. Nevertheless, the CCAP enumeration described below will be necessary either way.

The swap Operation

The core of the algorithm is a procedure called swap. swap exchanges an atomic index with another found in the same atomic number group. Source and target indexes of all edges are simultaneously updated to reflect the change. swap is invariant in the sense that the corresponding graphs before and after swap are constitutionally identical.

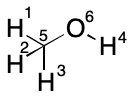

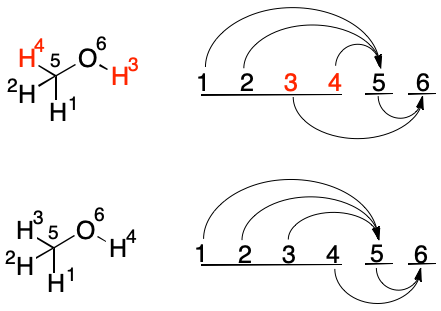

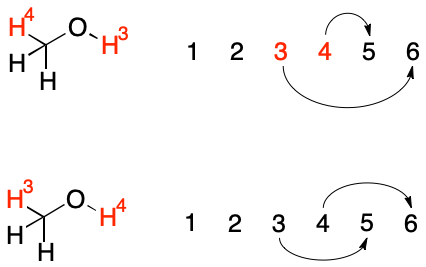

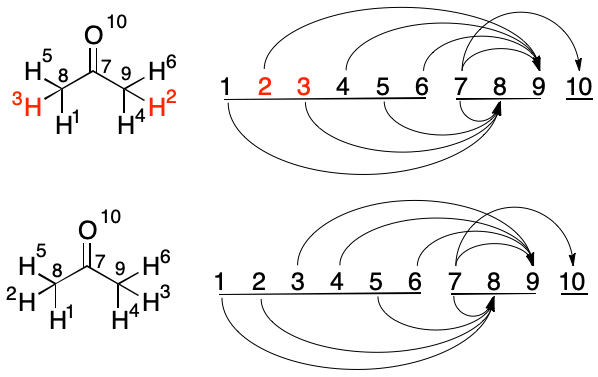

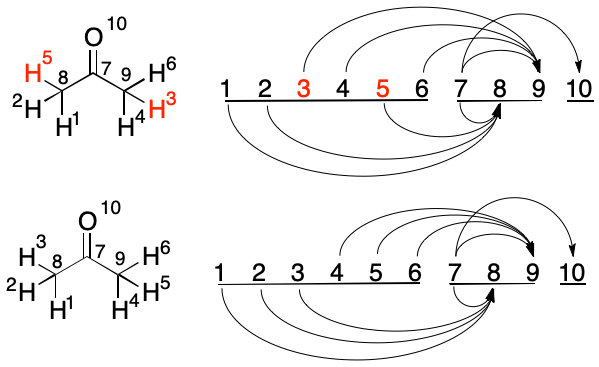

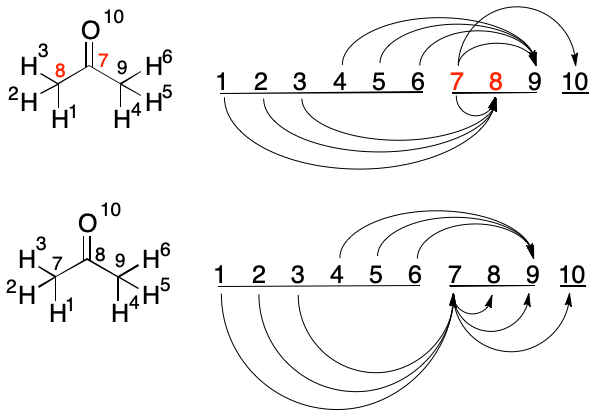

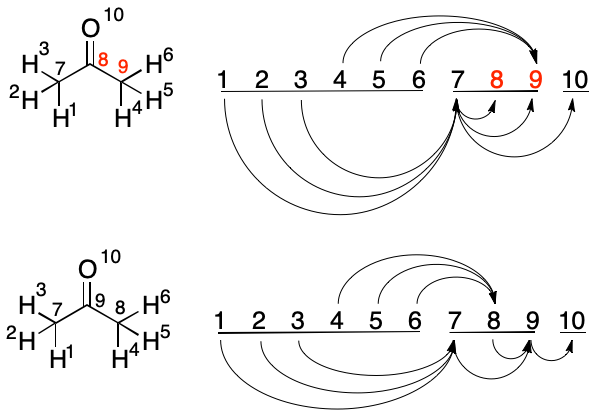

To visualize swap operations, I've developed a graphical representation. Atomic indexes are arranged horizontally with one appearing on the left and the maximum index appearing on the right. Bonds, represented as curved arrows, are then directed from source to target. Although a TUCAN molecular graph is undirected, edges are written as if they were directed from low index to high. The diagram captures this property.

Consider performing swap between two hydrogens in the methanol graph depicted above. Swapping constitutionally equivalent hydrogen atoms (e.g., 1 and 2) results in the same diagram and graph. However, swapping constitutionally distinct atoms (e.g., 3 and 4) leads to a change in the diagram and graph.

In a sense, swap doesn't re-index atoms, which always appear in the same sorted order, so much as it rewrites bonds.

Approach

Using swap as a building block, we can construct an algorithm for canonicalizing TUCAN representations:

- Consider each pair of atoms (

aandb) within a group individually and in order of atomic index. - If the criteria described below are met for the pair, swap

aandb. - Otherwise, continue to the next pair of atoms.

- If no pairs are available, proceed to the next group having higher atomic number.

- If no groups are available, exit.

The criteria in Step (2) are:

- For all inbound edges of

aandb, find the one with the greatest length. Doesswapdecrease the target index of the edge? - If no suitable edges of

aorbare available, find the outbound edge ofawith the greatest length. Doesswapdecrease the target index of the edge?

A "yes" to either question, asked in sequence, causes the condition to pass, leading to subsequent execution of swap.

Example

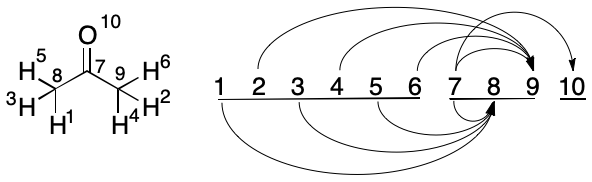

Consider the problem of finding the canonical TUCAN string for acetone. Starting with Step (1), we consider Atoms 1 and 2 as a candidate pair. Atom 1 has one outbound edge, but after swap its target index does not decrease. The same holds for every pairing of Atom 1, so we continue to Atom 2.

Atoms 2 and 3 are considered. Atom 2 has one outbound edge, (2, 9). Its target index would decrease after a swap (2, 8). The swap takes place and the new Atom 3 is considered.

The swaps available to Atom 3 are considered, starting with Atom 4. Each atom has one outbound edge, but with the same target. Swapping can not change the target index, so the pair is rejected. A swap between Atoms 3 and 5 is then considered. Both have one outbound edge. The new Atom 3 would have a target of 8 rather than its current target of 9, so the swap is performed. The algorithm proceeds to the next index.

Swapping Atoms 4 and 5 would lead to no change because both have a single edge pointing to the same target. The same applies to Atoms 4 and 6. Atom 5 is now considered.

As before, swapping Atoms 5 and 6 would lead to no change because both have a single outbound edge pointing to the same target. This concludes the examination of the hydrogen block. As per Step (4) of the algorithm, we continue to the next block containing carbon atoms. The first atom has index 7.

The possible swap between Atoms 7 and 8 is the first time that inbound edges must be considered. The inbound edge (1, 8) is the longest. Swapping atoms 7 and 8 would reduce the target index from 8 to 7. Therefore, the swap is performed. All of the edges involving either atom are reconstructed. Atom 8 is now examined.

A swap between Atoms 8 and 9 is considered. The target index of the longest inbound edge (4, 9) would be reduced from 9 to 8. The swap is therefore performed. This concludes the swap candidates in the carbon block.

The oxygen block contains a single member, Atom 10. We therefore continue to Step 5. Given that there are no further blocks to consider, the algorithm exists. The resulting indexes will now yield the canonical string for acetone, "C3H6O/1-7/2-7/3-7/4-8/5-8/6-8/7-9/8-9/9-10".

Conclusion

Molecular canonicalization can be thought of as proceeding in two phases: an initial partitioning step followed by a brute-force iteration. The TUCAN identifier is unique in that its serialization imposes an initial partitioning. This article outlined an iteration procedure with diagrams for visualizing the computation of a canonical TUCAN string starting from an uncanonicalized representation. Several opportunities exist for refining this procedure through better initial partitioning.