Molecular Graph Canonicalization

Many kinds of molecular encoding are used in cheminformatics, but all are based on the concept of a molecular graph. A molecular graph is a graph whose nodes and edges are augmented to capture information relevant to molecular structure. Generally speaking, atoms map to nodes and bonds map to edges.

Comparing two graphs for equivalence turns out to be challenging compared to other kinds of comparisons. Data structures like lists (e.g, strings and arrays) offer a simple, linear time approach: iterate the elements of both lists in parallel, returning false at the first mismatch or true if no mismatch is found. This linear approach is not directly applicable to graph comparisons, but with some work the problem can be recast as a linear search. This article describes the idea at a high level, offering a simple conceptual framework for a rather large body of literature.

Applications

Before diving into solutions, it's worth noting some situations in which graph equivalence crops up. Most applications of graph equivalence arise in the context of creating and using molecular sets. A set contains no duplicates, so a molecular set requires a method for comparing two molecular graphs for equivalence. Such comparisons must occur whenever a member is added, removed, edited, or queried. Molecular sets are widely used in cheminformatics.

One of the most import kinds of molecular set is the registration system. A registration system is a molecular set used by an organization to enforce not just graph equivalence, but more restrictive business rules as well. These often involve the perception of tautomerism, stereoisomerism, salt forms, and other higher forms of equivalence. Registration systems are typically complex, with layers of protocol for read and write access. An example is the Chemical Abstracts Service Registry. This registration system contains over 188 million substances, many of which are represented as graphs. Pharmaceutical companies typically maintain their own registration systems, each with a slightly different set of business rules.

But molecular sets that act like registries can follow much simpler rules as well. Here are but a few examples:

- Molecular Assembly Index, a topic recently covered here, uses the presence of a newly-generated molecule in a collection as the basis for a metric of molecular complexity relevant to the origins of life.

- Mapping chemical structure to properties requires a suitable method to identify and prevent duplicates. This topic lies in the vast area known as molecular standardization.

- The enumeration of the members of any chemical space, regardless of size, requires a method to identify and eliminate duplicates. GDB is one example.

The need to check for molecular equivalence is pervasive in cheminformatics because molecular sets tend to show up wherever molecular graphs do.

Automorphism

Up to this point I've been using the term "equivalent" rather loosely. What I mean is automorphic. Automorphism occurs when a graph is found to be isomorphic with itself. Like isomorphism, automorphism is associated with a mapping (or "permutation") of atoms from query to target graph. Because each represents the same graph, an automorphism maps each node to either itself or another member node.

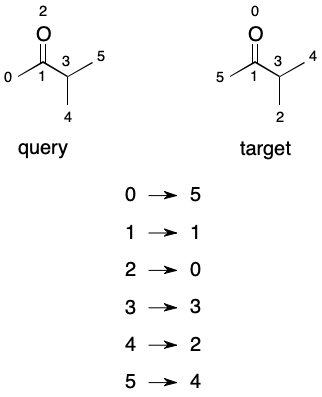

A permutation can be thought of as an ordering the nodes of a graph. Imagine that we find an automorphism between two graphs of six nodes: (0→5); (1→1); (2→0); (3→3); (4→2); (5→4). An equivalent form would be the array [5, 1, 0, 3, 2, 4]. The array form reveals that under the mapping node 5 comes first, followed by nodes 1, 0, 3, 2, and 4, in that order.

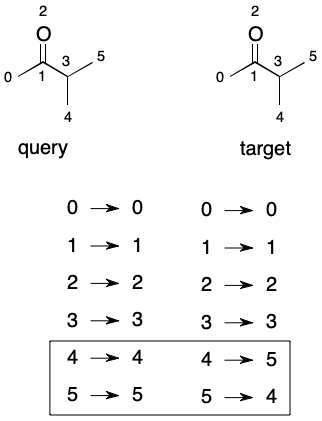

Something interesting happens when the mappings for two automorphic graphs with identical node orderings are exhaustively enumerated. The result is an automorphism group. An automorphism group partitions the nodes of a graph into equivalent sets (aka "orbits"). The number of orbits and their occupancy describes the symmetry properties of a graph. As we'll see, the automorphism group also plays important role in graph equivalence problem.

Brute-Forcing Automorphism

Brute force is an effective method for determining whether two graphs of equal size and order, A and B, are automorphic. Pick a random node from A and call it a. Pick a random node from B and call it b. Do all relevant local properties of a and b match (e.g., degree, atomic number, charge, isotope, stereochemical configuration)? If a and b don't match, pick another node from B and try again. If a and b do match, pick a random neighbor of a, pick a random neighbor of b, and try to match them. Continue this process, backing out and retrying again as needed, until either all nodes have been matched or no matching node b can be found.

A procedure very much like this one underpins the VF2 and Ullmann algorithms. These algorithms are designed for the more general problem of isomorphism. Brute force is the only option when query and target graphs have unequal sizes (edge count), orders (node counts), or both. However, when node and edge counts are identical across query and target, as they are in the case of automorphism, we can do better.

Canonicalization

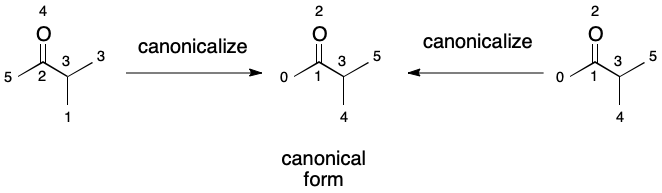

The efficiency of detecting an automorphism condition can be increased through canonicalization. In the context of graphs, canonicalization is the process of selecting one representation out of all possible representations. This is usually accomplished through the identification of an ordering of nodes that leads to the canonical form. For example, methanol has two possible representations: one in which the atom ordering places carbon ahead of oxygen, and one which places oxygen ahead of carbon. Each ordering leads to a different representation.

It turns out that this problem can be transformed into one that looks more like list comparison through canonicalization. Canonicalize both graphs, A and B, then compare each list of atoms. At the first mismatch, report no automorphism, otherwise report that an automorphism exists.

At first glance, this operation may not appear to have achieved much. We must still canonicalize both the query and target graphs. That doesn't come cheap. Recall, however, the context in which most automorphism comparisons occur: molecular sets. The canonical form of all members can be computed and cached. Querying the set boils down to canonicalizing the query graph and performing a list-like comparison operation over the set. This approach really shines when seeking the intersection of two molecular sets as when two registry systems are merged or joined. In this sense, a canonicalized graph serves as a kind of foreign key. Not only that, but we can take advantage of hashing to perform extremely efficient molecular lookups. This offers primary key functionality.

All it takes to get these benefits is a canonicalization algorithm.

Brute Forcing Canonicalization

Many canonicalization algorithms have been developed. Like isomorphism algorithms, each canonicalization algorithm has at its core a simple kernel that can be expressed as a brute force procedure. For canonicalization, that kernel is the generation of a code.

As defined by Ivanciuc, a code is a string (character sequence) obtained through algorithmic transformation of a graph. A code has the useful property of being transformable into the graph that generated it. For example, SMILES fits the definition of a molecular code. Molecular graphs can be transformed to and from SMILES representation algorithmically. InChI, on the other hand, does not qualify as a code because an InChI string can't be transformed, generally speaking, into a molecular graph. An InChI with "auxiliary information," however, does qualify as a code, a feature that was successfully used to generate canonical SMILES using InChI.

The availability of a molecular coding scheme like SMILES makes it possible to define a brute force canonicalization algorithm for a molecular graph G:

- Generate the set of all possible SMILES,

S, fromG. - Select the lexicographically smallest SMILES,

s, fromS. The order of characters can be derived from ASCII. - The canonical form of

Gis the molecular graph that results from readings.

Imagine using this procedure to canonicalize isopropanol. We begin by generating all possible SMILES:

- OC(C)C

- CC(C)O

- CC(O)C

- C(C)(C)O

- C(O)(C)C

The ASCII character set associates each character with a unique number. The parentheses symbols precede the letters, with the left parentheses symbol (() preceding the right ()). The SMILES for isopropanol can therefore be sorted in ascending lexicographical order as follows:

- C(C)(C)O

- C(O)(C)C

- CC(C)O

- CC(O)C

- OC(C)C

From this ranking we conclude that the canonical form of isopropanol is the one produced from reading the SMILES C(C)(C)O.

Using this procedure requires some attention to detail. For example, it's important to ensure that the rules explicitly state when and how hydrogen suppression may be used. Likewise, we'd want to ensure that ring closure digits followed a set of consistent rules to avoid useless diversity.

The main problem with the brute force approach as stated is inefficiency. A given molecular graph with n nodes will have up to n! different node orderings. For example, isopropanol with four heavy atoms has 24 (4!) possible orderings. This factorial scaling of the number of atom orderings bodes poorly for the brute force method.

Notice, however, that only five unique SMILES for isopropanol are enumerated by brute force. What's going on here? The answer is twofold: syntax and symmetry.

SMILES encoding yields atom indexes that follow a depth-first traversal pattern. This pattern eliminates many otherwise valid atom orderings. For example, it would be impossible to express a SMILES for isopropanol in which a primary carbon immediately preceded the oxygen atom because these two atoms are not bound to each other.

A second factor is symmetry. Take the canonical SMILES, C(C)(C)O, for example. This form actually represents two equivalent numberings due to the topological equivalence of the methyl groups. Each of the five candidates in fact represents two different atom numbering systems due to symmetry. Symmetry reduced ten possible SMILES candidates to five.

Optimization Strategies

SMILES syntax and molecular topological equivalence act to reduce the number of candidate SMILES. What other rules could be applied to further reduce the search space? What would it take to reduce the search space to one candidate? These are questions related to optimization.

As mentioned previously, SMILES offers a powerful type of optimization essentially for free, by virtue of its its syntax. That optimization eliminates atom orderings that can't follow from a depth-first traversal.

We can view the enumeration of all possible SMILES as a set of search trees, each one rooted at a starting atom. Each tree is terminated by a different candidate SMILES. What we'd like is a set of procedures that terminate the exploration of a search tree at the earliest possible point.

The question then becomes, what other optimizations can be applied to terminate the exploration of unproductive search trees?

Invariants

The process of optimizing molecular canonicalization often begins with graph invariants. An invariant is a property of a graph that does not change with node ordering.

Take the number of nodes of a graph (aka "order"), for example. Regardless of how nodes are ordered, the total number of nodes never changes. The same applies to edge count. But even though they are invariant, node and edge counts won't help us create more efficient canonicalization schemes.

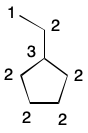

What will help are invariants that can partition atoms. For example, degree is the number of neighbors attached to a node. Regardless of what index it carries, the degree of a node remains constant. Atomic number is another graph invariant. Regardless of how a molecular graph is encoded, the atomic number of its atoms will never change. Other atom invariants include isotope and charge.

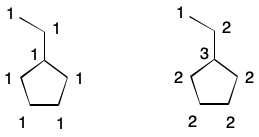

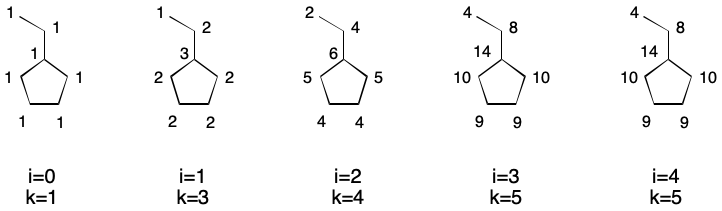

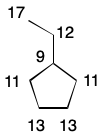

A large number of graph invariants have been described over the last few decades, many in the context of molecular graphs. For example, the idea of degree can be generalized to extended connectivity. Whereas degree only takes into account the connectivity of a given atom, extended connectivity accounts for the connectivity of neighbors, their neighbors and so on.

To illustrate, consider an alternative definition of degree. Begin by labeling each atom with the index 1. Now compute the degree of a given atom as the sum of each neighbor's index. The tertiary carbon in isopropanol, for example, has three neighbors, each having an index of one. The degree of the tertiary carbon is therefore three (3*1).

Extended connectivity takes this idea one step further by introducing iterations. After the first iteration, update the index of each atom with the result of the previous calculation. For the second iteration (i=1), this is the degree of each atom. Continue iterating until the number of unique indexes does not increase. This is the basis for the well-known Morgan Algorithm.

Another node invariant is distance sum. The distance sum for a node is the sum of all shortest path lengths to every other node. Computing this invariant requires n - 1 breadth-first traversals for every node and so scales quadratically with the number of nodes.

Some molecules possess features that cause many atoms to resist symmetry partitioning. Consider cubane, whose eight carbon atoms are topologically equivalent. None of the invariants so far described can differentiate these atoms. Nor is cubane the only example. Fullerenes such as C60 are composed of large numbers of topologically equivalent atoms. Fortunately, the selection of the first atom can impose asymmetry which, when coupled with iterative comparison, leads to efficient pruning of the search tree.

Degree, extended connectivity, and distance sum are but some examples of the invariants that can be applied to optimize a canonicalization algorithm.

Choosing a Node

Given that SMILES strings derive from a depth-first traversal of a molecular graph, the selection of the starting node would seem to offer a good place to look for optimizations. In fact, the careful selection of the starting node can prune entire branches of the search space.

Recall that the candidate SMILES strings for isopropanol, ranked in ascending lexicographical order, are:

- C(C)(C)O

- C(O)(C)C

- CC(C)O

- CC(O)C

- OC(C)C

Some of the simple invariants that might be considered when choosing the first atom include:

- Degree. Starting with the atom of highest degree reduces the number of candidates to two: 1 and 2.

- Atomic number. Starting with the atom of highest atomic number reduces the candidates to just one: 5.

- Extended connectivity. Starting with the atom of highest extended connectivity reduces the number of candidates to two: 1 and 2.

- Distance sum. Starting with the atom of lowest distance sum reduces the number of candidates to two: 1 and 2.

These invariants can be (and often are) combined in various ways. For example, Weininger uses the invariants: degree; virtual hydrogen count; graph hydrogen count; atomic number; sign of charge; absolute charge; and total hydrogen count.

Depending on the desired level of optimization, still more invariants can be brought into play, mixed, and matched. Unfortunately, reports of such optimizations often don't reveal performance benchmarks, which complicates evaluation.

When selecting subsequent atoms, either the same invariant set or a different one can be used. Additional heuristics can also be brought into play. For example, we might prefer to traverse nodes connected to previously-traversed nodes.

Note that a valid canonicalization will result even from invariants of low discriminatory ability. Clearly, a brute force procedure without invariants works just fine. The selection of invariants isn't about obtaining a valid result, but rather obtaining it more efficiently.

Conclusion

Molecular canonicalization is a complex topic, but fortunately the underlying principles are easy to understand. This article presents a mental model for canonicalization that uses a brute force approach as the base case. From that base, the various optimizations that have been developed over the last few decades can be explored.