Writing Aromatic SMILES

SMILES is a de facto standard for chemical structure representation. The core language can be picked up quickly, but just below the surface lie some surprisingly complex concepts. One of the most difficult of these is "aromaticity." A previous article described a comprehensive approach to reading aromatic SMILES. The following article details a method for writing aromatic SMILES.

Aromatic SMILES

SMILES atoms and bonds support a boolean flag designating them as aromatic. This flag is set through syntax that will be described below. Setting the aromatic flag on an atom can change the way that implicit hydrogens are computed in non-obvious ways. There is furthermore much confusion around the exact meaning of a bond whose aromatic flag has been set. Assuming that aromatic flags have been set properly, their use can incur computational costs that scale superlinearly with atom count. It's therefore crucial to understand the semantics and performance tradeoffs involved, whether you're writing SMILES software or merely using SMILES.

Why Aromaticity?

Before considering how to write aromatic SMILES, let's tackle the simpler question of why you might want to do that in the first place. The use of aromaticity incurs non-negligible overhead, both for readers and writers. So it makes sense to ensure that the benefit justifies the cost.

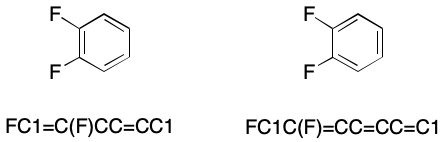

To be clear, aromaticity in SMILES is an optional feature. Any molecule that can be written using aromatic flags can also be written in Kekulé form. Kekulé form expresses the electronic structure of a molecule using bond types having integer formal bond order. Consider 1,2-difluorobenzene. Its Kekulé forms represent the electronic structure of the ring as alternating single and double bonds.

The aromatic form represents exactly the same molecule, but permits bond elision. Bond elision in SMILES is the practice of leaving out bonds without loss of structural information. For example, we can write an aromatic SMILES for 1,2-difluorobenzene in which all bonds are elided. This is possible because the ring atoms have been marked as aromatic with lowercase symbols.

Therefore, one reason to write aromatic SMILES is convenience. Eliding bonds simplifies manual encoding of SMILES, something that you can test for yourself. The idea is that this shortcut leads to faster and less error-prone data entry in interactive environments such as a REPL or notebook.

Although convenience during manual entry might justify the need for software that reads aromatic SMILES, it doesn't justify the need for software that writes aromatic SMILES.

Another reason to write aromatic SMILES is tradition. Many toolkits default to aromatic output and so this form has become familiar. But familiarity is subjective, and as noted before, presenting SMILES to end users can be be considered an anti-pattern.

Some sources mention the ability of aromatic SMILES to carry chemical meaning. However, the SMILES documentation is clear: no chemical meaning can be ascribed to aromatic SMILES. As noted by Dave Weininger, creator of SMILES:

“Aromatic” means “it smells nice”. No kidding, that is the only defensible definition. There is no single rigorous definition of aromaticity in chemistry. To a synthetic chemist, aromaticity implies something about reactivity; to a thermodynamicist, about heat of formation; to a spectroscopist, about NMR ring current; to a molecular modeler, about geometrical planarity; to a cosmetic chemist, it probably means “smells nice”. The SMILES definition of aromaticity has nothing to do with the other definitions, except that we would all agree that benzene is “aromatic”.

Despite the misappropriation of a name dripping with chemical history and controversy, aromaticity in SMILES is purely a language construct, with no physical significance whatsoever. Applications that export aromatic SMILES for the purpose of conveying chemical meaning run the very real risk of being misinterpreted.

This brings us to the original and still best reason for a software implementation to encode aromatic SMILES: to yield a unique molecular identifier for applications such as constant-time lookup (aka "canonicalization," as described in the next section). But as we'll soon see, aromatic SMILES is unnecessary even in this context.

More recently, a secondary motivation for writing aromatic SMILES has come into play: machine learning. Numerous papers report the direct use of SMILES strings in machine learning projects. For leading references, see DeepSMILES and SELFIES. Most studies use aromatic SMILES but to my knowledge the effect, if any, of doing so has never been addressed.

When it comes down to it, the justification for using aromatic SMILES in many situations is rather flimsy. Nevertheless, aromatic SMILES are ubiquitous.

Canonicalization

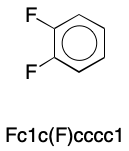

By itself SMILES is not suitable as a unique molecular identifier. A SMILES string encodes a depth-first traversal over a molecular graph. The specific form this string takes reflects both representational details and the relative ordering of atoms. For example, propane can be represented by two different SMILES strings depending on whether the ordering places the secondary carbon before or after the primary carbons.

Given a unique atom ordering, SMILES can be used as a unique molecular identifier. This can be accomplished through canonicalization. In computer science, canonicalization is the process of choosing one representation out of more than one possibility. A molecular graph is canonicalized through the application of a deterministic system for encoding features, and a deterministic ordering of nodes.

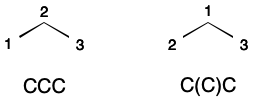

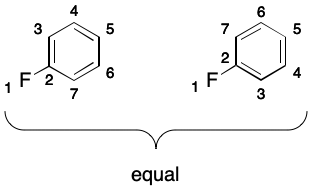

A complicating factor is delocalization-induced molecular equality (DIME). DIME occurs when a molecule can be represented by two or more unequal graphs ("contributing graphs") that must nevertheless be considered equal. For example, it's easy to identify two unequal contributing graphs for 1,2-difluorobenzene. Even if we develop a unique atom ordering for this molecule, there will be two contributing graphs and therefore two SMILES.

As explained by Weininger, the main purpose of aromaticity in SMILES is to enable canonicalization through the elimination of contributing graphs:

The SMILES language was specifically designed to be “canonicalizable”, i.e. not only to provide an unambiguous chemical nomenclature but also be able to express a single, unique SMILES for every structure in the same language. This implies a fundamental requirement to express the symmetry of a molecule correctly. Consider the problem of generating a unique SMILES for OclccccclF ortho-fluorophenol, but without aromatic bonds. There are two ways to write it, OCl=CC=CC=ClF (with the substituted carbons joined by a single bond) and OCl=C(F)C=CC=Cl (with the substituted carbons joined by a double bond). These are two different molecular graphs: the SMILES for these will always differ. For purposes of unique nomenclature, it is not acceptable to have two different “unique SMILES” for the same molecule. SMILES language provides an “aromatic” concept to avoid this conundrum.

One option, not considered by Weininger, is to refine the canonicalization procedure to set the position of double bonds capable of delocalization. In other words, we can pick one contributing graph over the other. This approach doesn't require the aromaticity flag at all.

Another approach is to use the aromaticity features of SMILES to elide bonds, as Weininger notes. Because double bonds are no longer being written, they can no longer give rise to multiple contributing graphs.

Notice, however, that regardless of the approach (using the aromatic flag or picking a contributing graph), exactly the same work must be done to identify contributing graphs. Aromatic SMILES does not absolve a canonicalizer of the responsibility to detect DIME. It merely eliminates the problem of picking a canonical form.

Nor is aromatic SMILES a complete solution to DIME. For example, your application may or may not consider cyclobutadiene contributing graphs to be equal. For its part, the experimental evidence suggests that cyclobutadiene contributing graphs should not be considered equal. Aromatic SMILES can only offer a tool to express contributing graph equality if desired. It does not absolve you of the need to decide whether doing so is appropriate. Moreover, many forms of DIME, such as tautomerism, can't be addressed through aromatic notation. Your application will need to discriminate contributing graphs anyway.

Delocalization Subgraph

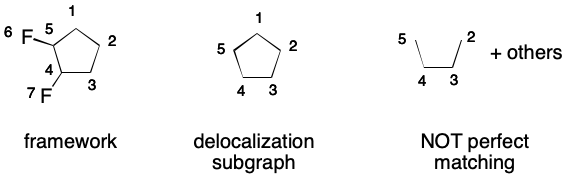

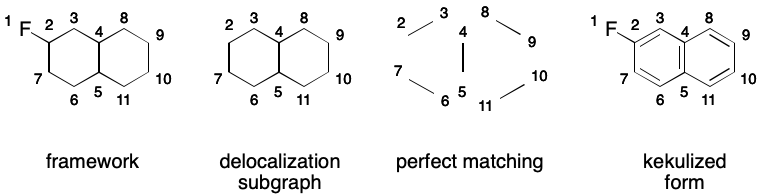

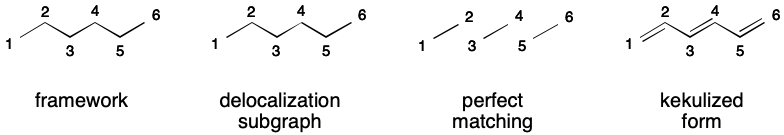

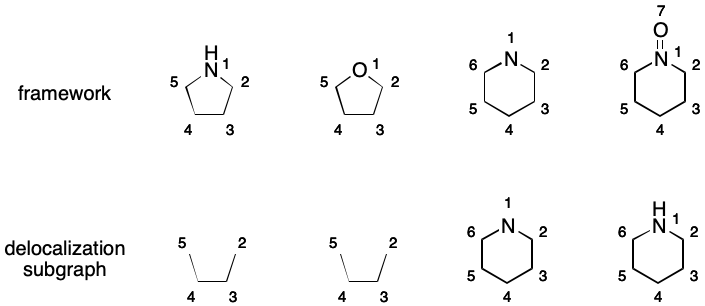

SMILES aromaticity revolves around an implicit construct I call the delocalization subgraph (DS). The DS is a possibly empty set of atoms and bonds (i.e., a "subgraph") that represent a delocalized electron system. Every SMILES is associated with a single DS, which may contain disconnected components. Any bond contained within the DS can be elided. This yields representations that eliminates certain forms of DME.

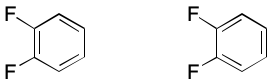

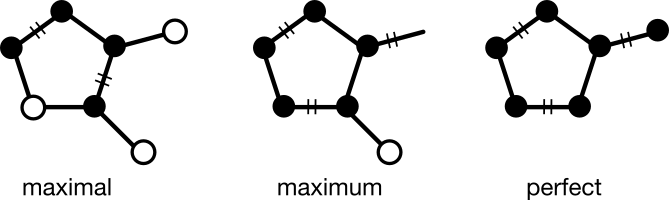

Consider 1,2-difluorobenzene. Its DS includes all of the atoms and all of the bonds in the six-membered ring.

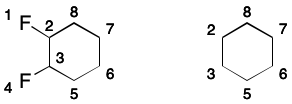

A SMILES containing a DS makes a very specific promise to readers: the DS will have a perfect matching. As explained previously, a matching is a subgraph in which no two edges share a common node. A perfect matching covers all nodes of the parent graph. Put another way, a SMILES will only be valid if a perfect matching over its DS exists. For monocyclic systems, two equivalent perfect matchings will exist, and each will correspond to a contributing graph.

For example, the following DS for 1,2-difluorobenzene is valid because a perfect matching over its DS exists.

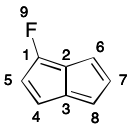

An invalid SMILES results when a DS without a perfect matching is created. Consider, the cyclopentadienyl radical. Adding every atom and every bond to the DS results in a graph without a perfect matching. Therefore, the corresponding SMILES is invalid.

A DS must have a perfect matching because this is the way that an aromatic representation is Kekulized. Kekulization is the transformation of a SMILES representation that uses aromatic notation into one that does not. The first step of kekulization is to obtain a perfect matching over the DS. Then, elided bonds are replaced by with double bonds for each edge in the matching.

Although a perfect matching must exist for a DS to be valid, there are many ways to satisfy this requirement. Consider hexatriene, which can be represented using aromatic notation by adding all carbons and the bonds between them to the DS. A perfect matching over the DS exists (exactly one!). The SMILES is therefore valid.

Of course, representing hexatriene in this way is unnecessary because there is only one contributing graph. However, it turns out that many uses of SMILES aromatic flags are unnecessary, even in cases purportedly trying to eliminate DIME.

Gratuitous Aromaticity and Pruning

If a writer fails to identify DIME before generating a SMILES, the result can be gratuitous aromaticity. Gratuitous aromaticity occurs when aromatic flags are set on features that don't induce contributing graphs. Gratuitous aromaticity, like gratuitous sex in the media, is not illegal, may appeal for reasons that are hard to put into words, and is rather widespread.

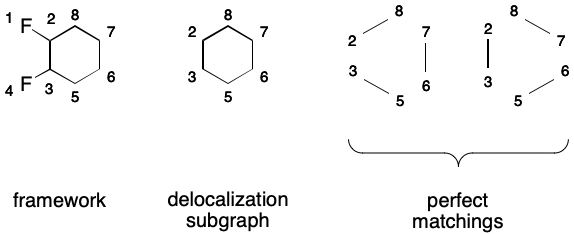

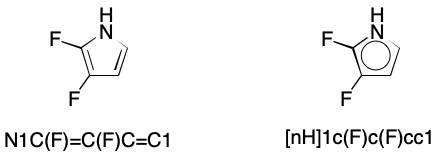

Consider 2,3-difluoropyrrole. Only one contributing graph exists, but the corresponding SMILES can be written without regard for this fact. Adding all cyclic atoms and the bonds between them to the DS yields a subgraph without a perfect matching.

To resolve this issue, SMILES readers supporting kekulization must be capable of a procedure I'll call pruning. As noted previously, pruning removes those atoms from a DS that are incapable of forming a double bond without introducing a radical or charge. The defining characteristic of atoms that will be pruned is a valence that equals a normal valence. This rule applies to both bracketed and unbracketed atoms. Pruning ensures that kekulization will generate no radicals or charges.

Although pruning offers a simple solution to a tricky problem for readers, it does nothing to address the root problem: 2,3-difluoropyrrole and many similar molecules don't require aromatic flags because their Kekulé forms do not lead to DIME.

This perspective simplifies a number of otherwise awkward issues. For example, some SMILES users advocate increasing the set of elements whose atoms can be marked as aromatic. Tellurium is a sometimes-cited example. But unless the goal is to support the canonicalization of tellurium analogs of pyridine, there's no need. Mere tellurophenes can't lead to DIME any more than furans can. So the need for aromatic tellurium can hardly be justified on the grounds of canonicalization.

Finally, it should be noted that gratuitous aromaticity can arise through symmetry. Consider fluorobenzene. The corresponding molecular graph does not exhibit DIME due to symmetry. Marking the ring atoms in this molecule as aromatic leads to gratuitous aromaticity.

Syntax

An atom's aromatic flag can be set by replacing the first letter of its element symbol with its lower case counterpart. For example, aromatic carbon is encoded by the element symbol "C" (c), nitrogen uses lowercase "N" (n), and so on. However, not every atom is eligible for this treatment.

Only those atoms associated with certain atomic symbols can accept the aromatic designation. Membership of the set is driven by the need to later kekulize without introducing charges or radicals. This allows us to place some requirements on the symbols of atoms that can be aromatized:

- The star, or wildcard symbol (

*). Regardless of its current valence, another double bond can always be made to a star atom without changing its other properties. - One or more "normal valences" are defined for the element. A normal valence is the number of hydrogens that can be attached to an isolated atom. Multiple normal valences are possible for some elements due to their support for an expanded octet. Normal valence is required information because only atoms with an unused valence can form a double bond during kekulization without introducing a charge or radical.

In practice, the halogens are excluded even though all are assigned normal valences. The reason seems to be that these elements rarely display valences beyond one, whereas a double bond requires at least divalence.

A bond is marked aromatic by using the colon symbol (:). The restrictions on its use are simple to state: there are none. The aromatic flag can be set on any bond because it will be ignored wherever it appears. In other words, the aromatic bond symbol is synonymous with bond elision. To maintain backward compatibility, readers must be able to read the the colon bond symbol. But writers should consider it deprecated in favor of bond elision.

Electron Cycles

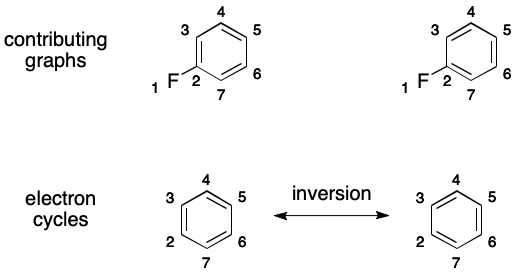

Atoms and bonds are added to a DS by detecting a molecular feature I call an electron cycle. An electron cycle is a cycle whose bond overlay contains an uninterrupted, alternating pattern of single and double bonds. When present, an electron cycle can induce multiple contributing graphs and therefore DIME.

The key to this phenomenon is inversion. Inversion toggles the order of the bonds in an electron cycle. More concretely, single bonds are replaced by double bonds and double bonds are replaced by single bonds. An inverted electron cycle is indistinguishable from the original except through the placement of double bonds. Neither atom connectivity nor hydrogen counts are affected.

For example, 1,2-difluorobenzene contains one electron cycle. Its inversion partitions the space of molecular graphs, leading to DIME.

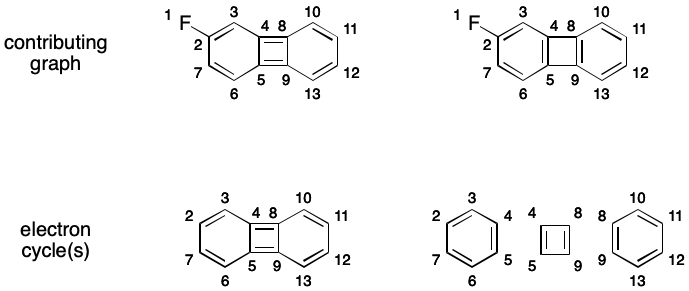

A given molecule's electron cycles can vary depending on the contributing graph being used. For example, one contributing graph for 2-fluorobiphenylene has a single electron cycle of size 12. Another contributing graph has two electron cycles of size six and one of size four.

Intermission: Huckel, Huckel, Toil and Trouble

The definition of electron cycle presented in the previous section is the narrowest one required for canonicalized output. However, some applications may require aromatic SMILES output for cosmetic reasons, to promote manual convenience, or aesthetics. Such uses can be accommodated by relaxing the definition of electron cycle, but at a price.

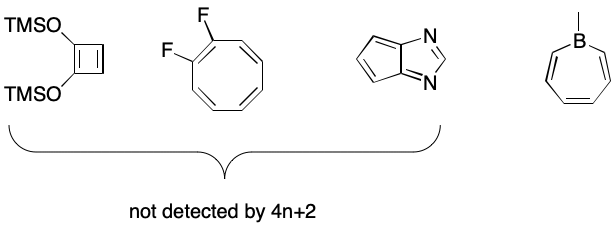

We can redefine the term "electron cycle" to mean a cycle whose bond overlay contains an alternating pattern of single and double bonds optionally interrupted by uncharged, isolated atoms possessing a nonbonding electron pair or electron hole. Under this definition, the concept of inversion disappears. In its place we might substitute a required electron count of 4n + 2, where n is a positive integer. A hole contributes zero electrons, a nonbonding pair contributes two. A double bond would contribute two electrons. This is similar to Hückel's often stated but poorly understood rule.

The main problem with this approach is that it excludes 4n systems such as cyclobutadienes, cyclooctatetraenes, pentalenes, and the like. This may or may not be desired or expected. On the positive, side, electron cycles such as the one in borepin would be detected.

A secondary problem is that SMILES has no concept of nonbonding electron pairs or electron holes, although some documentation may misleadingly imply its existence. Normal valences have no role to play here because they say nothing about electron holes or nonbonding pairs.

We could correct this situation by tabulating every aromatizable atom type in every possible valence state together with a contributing electron count. When iterating electron cycle candidates, we perform a test. If an atom is not bound to another atom in the cycle through a double bond, we ask two questions:

- Is the atom adjacent to another atom within the cycle lacking an internal double bond?

- Is the atom's environment missing from the table?

If the answer to either question is "yes," then the candidate electron cycle is rejected.

The table itself might contain entries like the following:

| Symbol | Valence | Electron Count |

|---|---|---|

| B | 2 | 1 |

| B | 3 | 0 |

| C | 2 | 2 |

| C | 3 | 1 |

| C | 4 | 0 |

| N | 2 | 3 |

| N | 3 | 2 |

| N | 4 | 1 |

| O | 2 | 2 |

| P | 2 | 1 |

| P | 3 | 2 |

| S | 2 | 2 |

| S | 4 | 1 |

Finding Electron Cycles

Electron cycles lead to the only form of DIME that aromatic SMILES was designed to address. Therefore, a SMILES writer capable of setting the aromatic flag on a kekulized molecular graph requires a reliable method for the exhaustive detection of electron cycles.

The following is such a method based on a directed depth-first traversal of a molecular graph (molecule).

- Create the empty sets

cyclesandatoms. - Pick an atom (

root) frommoleculenot inatoms. If none exists, returncycles. - Perform a directed DFS starting at

root. Follow an alternating single-double path. - On encountering a bond to

root, create a cycle (cycle) from the current path. Add the atoms ofcycletoatoms. Addcycletocycles. Continue traversal. - If traversal ends without the detection of an electron cycle, add

roottoatoms. - GOTO 2.

As an example, consider one of the 2-fluoropentalene contributing graphs. If atom 1 is chosen as root, directed traversal can proceed in the order 1-2-6-7-8-3-4-5-(1). This cycle is then added to cycles, and all of its atoms are added to atoms. Then the only atom not in atoms is 13. However, the only depth-first traversal open to it does not lead to a cycle. Atom 13 is then added to atoms. All of the molecule's atoms are now contained in atoms, so cycles is returned.

Notice however that depth-first traversal can just as easily uncover the nonproductive path 1-2-3-8-7-6. Therefore, the traversal must recognize such a situation and ensure the 2-6 branch is traversed regardless. Depending on the graph, this check can add considerable computational cost.

Alternatively, the set of all cycles can be generated using an algorithm like the one developed by Hanser. Each member of this set is then tested for the presence of an alternating overlay of single and double bonds. To accommodate uses beyond canonicalization, a less restrictive electron cycle definition could be used.

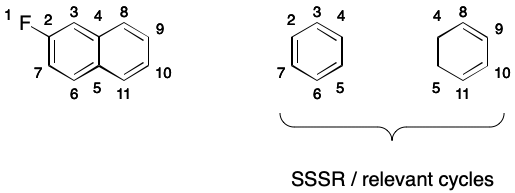

It's important to realize that we can't use a smallest set of smallest rings (SSSR) or the set of relevant cycles it find electron cycles. To see why, consider 2-fluoronapthalene. SSSR and the set of relevant cycles contain the smaller six- and four-membered rings but exclude the enveloping twelve-membered ring defining the electron cycle.

Regardless of whether or not aromaticity is encoded, a canonical SMILES writer must compute the set of electron cycles. Aromatic SMILES writers will use electron cycles to build a DS. Writers not using aromaticity will invert the electron cycles to find a canonical representation.

Building and Using a Delocalization Subgraph

It's now possible to formalize the requirements for the atoms and bonds in a DS. The DS contains all of the atoms found in at least one electron cycle. The DS also contains all of the bonds joining two DS member atoms. In other words, a DS is an edge-induced subgraph over those atoms belonging to one or more electron cycles.

The steps to build a DS from a molecule (molecule) for canonicalization purposes can be summarized as follows:

- Create an empty delocalization subgraph

ds. - Find all electron cycles (

cycles). - Add an atom to DS if it belongs to at least one cycle in

cycles. - For each bond (

bond) inmolecule, addbondtodsif both of its terminals are inds.

Unless steps are taken to address it, the set in Step (2) may contain cycles capable of inducing gratuitous aromaticity through symmetry. These can be eliminated prior to the use of cycles by finding the set of all automorphisms for molecule. A cycle in which at least one atom maps to another atom within the cycle can be pruned. Automorphism is a potentially expensive operation. However, canonicalization algorithms generally require this step (or one like it) anyway so its use in writing aromatic SMILES may not incur additional cost.

Conclusion

Aromaticity offers an optional way to encode bonding relationships in SMILES. Every aromatic SMILES can be transformed into a fully-equivalent kekulized counterpart. This property leads to several important constraints on SMILES writers. A complete treatment of writing aromatic SMILES, suitable for both canonicalization and other applications, is presented. The procedure is based on two implicit concepts that are discussed explicitly here: "delocalization subgraph" and "electron cycle." Both may have utility outside of SMILES.