Of Zero-Order Bonds and Bonding Systems

Cheminformatics and chemistry don't always move in tandem. A case in point is multi-atom bonding. Organometallic species, which have been made, characterized, and used for decades serve as the most obvious example. But there are more subtle cases as well, such as tautomers and mesomers. These species all highlight the problems of building cheminformatics on the shaky ground of valence bond theory.

Useful thought it may be for certain molecules, the two-atom valence bond is too restrictive for general use. What's needed is a more generalized concept for bonding. Many articles on this blog have documented the problem and possible solutions. See, for example Multi-Atom Bonding in Cheminformatics. A deep-rooted overhaul like this is bound to be disruptive, which in part explains the relative lack of progress.

Instead of a giant leap, is it possible to take baby steps? If so, what form might those steps take? This article describes one possibility.

The Zero-Order Bond

In 2010, Alex Clark proposed an approach to the problem of multi-atom bonding. Its purpose was to accomplish three goals:

- Capture all meaningful pairwise atomic interactions.

- Ensure the accuracy of implicit hydrogen counts.

- Enable maximum backward-compatibility with existing tools and practices.

To accomplish these goals, the proposal updates the molecular data structure in the following two ways:

- Each bond has a

bond_orderproperty that can assume one value chosen from the set { 0, 1, 2, 3 }. - Each atom has a

hydrogensproperty that can assume one value chosen from the set {automatic, 0, 1, 2, … }.

The assignment of the bond_order property is restricted in the sense that a value of zero must be used if either of the following is true:

- The bond is dative, without atomic charge correction. In other words, it is a single bond in which both electrons come from the same atom, and atomic charges don't reflect that fact.

- The bond order is any value other than 1, 2, or 3.

Only the elements C, N, P, O, and S are eligible for automatic hydrogen counting. Atoms containing any other element must use a numerical value. The following formulas are used to compute an automatic hydrogen count:

- carbon: 4 - |

charge| -unused_electrons-valence; - nitrogen and phosphorous: 3 - |

charge| -unused_electrons-valence; - oxygen and sulfur: 2 + |

charge| -unused_electrons-valence;

where:

unused_electronsis the number of unused bonding electrons, which will be non-zero for radicals and carbenes;valenceis the sum of bond orders.

Readers of this blog will recognize the hydrogens property as a form of hydrogen suppression. The automatic setting corresponds to implicit hydrogen, whereas a numerical value corresponds to virtual hydrogens.

In this article, I'll use the abbreviation ZOB ("zero-order bond") when referring to this proposal, but the part about counting hydrogens is crucial. Having laid out the rules for the ZOB proposal, let's have a look at how to use it in practice.

Examples

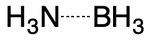

The coordinate covalent bond (i.e., "dative bonding") is a type of single bond in which one atom contributes both electrons. A simple example is the ammonia-borane adduct. The B-N bond can be thought of as containing two electrons drawn from nitrogen and zero electrons drawn from boron.

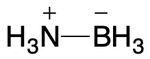

Applying a zero-order bond representation to this case is straightforward. We start with hydrogen count, noting that nitrogen can use automatic counting but boron can not. The B-N bond is dative, so its order is set to 0. The implicit hydrogen count on nitrogen is computed to be 3 (3 - 0 - 0 - 0). This representation succeeds in capturing the important B-N dative bond while also yielding an accurate hydrogen count for all atoms.

Alternatively, the bond between nitrogen and boron could be single, with atomic charges modified to ensure correct implicit hydrogen counts. This is the most likely representation today.

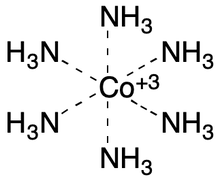

Zero-order bonds can be generalized to many other kinds of metal complexes. For example, the ZOB paper notes the advantages of using zero-order bonds with complexes such as [Co(NH3)6]3+: human-readability; the charge on the metal is unsurprising; implicit (automatic) hydrogen counting on nitrogen just works; and the important interaction between the metal and the nitrogen atoms is captured. Other representations using charge separation, a plain single bond, or even double bonds don't work as well.

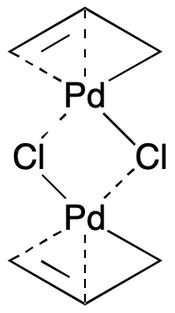

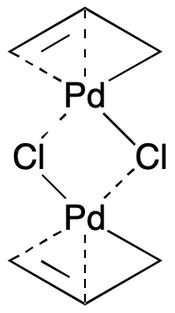

Multi-centered bonding like the kind found in organometallics poses especially tough challenges in cheminformatics. The very nature of the phenomenon is precluded by the two-atom valence bond model ubiquitous in file formats, drawing tools, and toolkits. Zero-order bonds can be used here as well, as illustrated by the allylpalladium chloride dimer.

Notice the mixed use of single and zero-order bonds between Pd-C and Pd-Cl pairs. This allows all meaningful interactions between atom pairs to be recorded, without distorting implicit hydrogen counts. Similar considerations apply with more complex examples, including metallocenes and cage compounds. However, the approach does introduce artificially asymmetrical bonding relationships. We'll return to this point later.

Implementation

Backward-compatibility is an important design goal with the ZOB proposal. To illustrate, the paper explains how to retrofit the properties block of the V2000 molfile format to support zero-order bonding. Three new properties are added:

M ZCH. Overrides the built-in charge property (M CHG).M HYD. Thehydrogensatomic property as defined above. If this property is not set for an atom, then it defaults toautomatic.M ZBO. Overrides bond order given in the bond block.

The example of the borane-ammonia complex discussed above would be represented in a ZBO-aware V2000 molfile as follows:

Molecule Name

File Descriptor

Comments

2 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0999 V2000

0.0000 0.0000 0.0000 B 0 5 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

1.5000 0.0000 0.0000 N 0 3 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

1 2 1 0 0 0 0

M CHG 2 1 -1 2 1

M ZCH 2 1 0 2 0

M HYD 1 1 3

M ZBO 1 1 0

M END

Backward-compatibility with non-ZBO implementations is possible because the V2000 specification states that unrecognized properties are ignored. This means that a reader that doesn't understand ZBO will interpret the file as a charge-separated, single bond representation.

But ZBO-aware implementations will behave differently. Noting the M ZCH property, the charges on each atom will be set to zero. The M HYD property will set the hydrogen count on boron (Atom 1) to 3. Finally, the M ZBO property will set the order of the B-N bond to zero.

What this treatment ignores is the somewhat obscure fact that V2000 defines its own rules for hydrogen counting. Both implicit and virtual hydrogens are supported. The way this works is neither intuitive nor easy to explain. For details, see the linked article. The system is arcane enough that I suspect it would be non-trivial to implement and test an extension that correctly handled every possible way in which native and ZBO hydrogen suppression could interact.

Applications

Although first described ten years ago, the ZBO proposal has gained renewed current relevance as a possible way to extend InChI for use with organometallics. The idea is covered in at least five public documents:

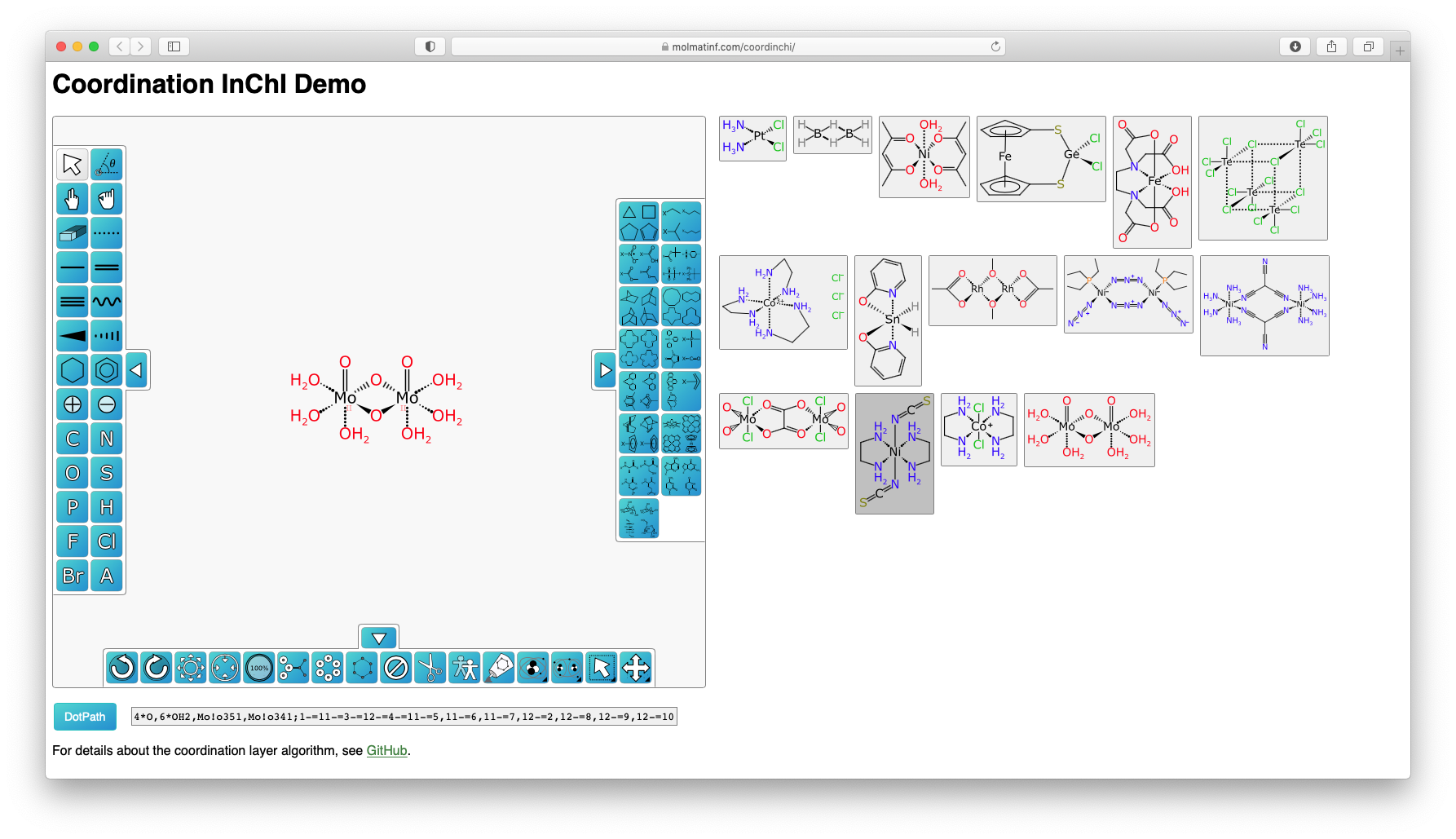

- Coordination Complexes for InChI: preliminary study. A validation set and an interactive tool with a proof-of-concept for organometallic InChI. The README explains the theory behind the implementation.

- Coordination Complexes for InChI: phase 2 study. Addresses comments and issues raised in response to Phase 1, in particular ways to address stereochemistry.

- Coordination InChI for inorganics: now with stereochemistry. Discusses non-traditional stereochemistry and InChI in the context of inorganics and organometallics.

- InChI for inorganics. Explains the method used to obtain real-world examples of organometallics from the CCCD.

- Coordination InChI: Preliminary survey of organic compounds. A slide deck from 2019 that sets the stage for adapting InChI for organometallics.

The ZBO proposal factors prominently in each of these documents, if not explicitly.

Tradeoffs

There are reasons that cheminformatics lags chemistry when it comes to the representation of bonding in organometallics: the problem is very hard and current solutions are entrenched. Every new solution brings with it tradeoffs of one kind or another. Finding a representational system is only one part of the problem because any new system has the potential to break what currently works. The ZBO proposal is no different.

An obvious tradeoff of using ZBO is that in some cases, formal charge and bond order become meaningless. Sometimes this won't matter, but sometimes it will. Knowing the difference can be extraordinarily difficult without in-depth knowledge of exactly how bonds are being used.

Take molecular descriptors, for example. Many of them rely on bond orders. What should happen when a descriptor calculation encounters a zero-order bond? Should it be ignored? Should it be flagged and/or logged? Should an attempt be made to compute a fractional bond order? What changes if the computation only uses atomic degree (number of attached atoms) rather than valence? These are not easy questions.

Similarly, zero-order bonds can complicate certain kinds of database queries. For example, a query requesting all cases of nitrogen bound to boron may fail if zero-order bonds are disregarded by the algorithm prior to search.

Another tradeoff is asymmetry. Specifically, zero-order bonds introduce artificial asymmetry. Consider once again the representation of allylpalladium chloride dimer. Organometallic chemists would be quick to point out that the symmetry of the two terminal carbon atoms is artificially broken when implementing the ZOB proposal. Sometimes distinctions like this will not matter, but sometimes they'll matter a lot.

Notice, however, that these tradeoffs are beyond the scope of the ZOB proposal's goals, which to re-iterate are capturing all meaningful pairwise atomic interactions; ensuring correct hydrogen counts; and backward-compatibility.

The Bigger Picture

In some ways, the tradeoffs of the ZOB proposal merely reflect the problems of the status quo reliance on the two-atom valence bond model.

To understand the underlying problem and its solutions, it's helpful to define two terms in the context of molecular representations:

- attribute: An assignable value. The term is derived from the French for "to assign".

- computation: A mathematical operation over one or more molecular attributes.

Both ZOB and the status quo view bonder order and formal charge as attributes. This means that both values are assignable values within a molecular graph. Finding the order of a bond means looking up the value assigned to that property. Likewise, to get an atom's formal charge, read the charge value.

In an earlier article, Formal Charge and Bond Order are Side Effects, I explained some of the problems with this model. I also described a system that eliminates these problems. Rather than viewing bond order as an assignable property, it is better viewed as computation. Likewise, formal charge results from a computation. In other words, formal charge and bond order are computed from molecular attributes.

It may not be obvious, but this alternative view places particle counts at the center of focus. If a value does not represent a particle count, it's likely to be a computation. Viewed from this perspective it's clear why both formal charge and bond order would be considered computations, not attributes. It's also clear why proton count, neutron count, electron count, and virtual hydrogen count would all be considered attributes.

Although the ZOB proposal does not share this particle-centric perspective, it does offer qualities that could be complementary.

Welcome to Electron Delocalization Island

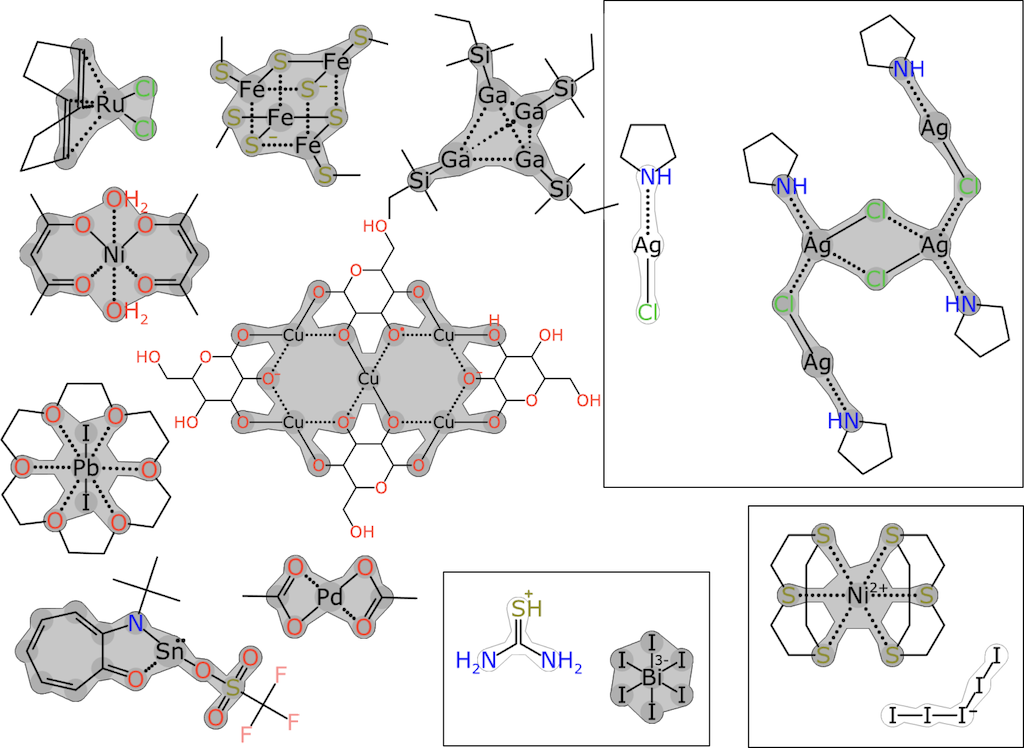

One of the topics covered in Coordination Complexes for InChI: preliminary study is how to translate ZOB representations into something that can be processed by InChI software. In doing so, the concept of electron delocalization island is introduced:

The concept of an electron delocalisation island is that each of these marks a subgraph whereby electrons can freely equilibrate. Making use of this idea is best done by enumerating the exceptions: for simple cheminformatics purposes, it is a reasonable working rule that electrons do not jump between connected components; and, heavily saturated main group atoms with no pi-bonds, or charges, or Lewis acid/base characteristics, generally do not allow electrons to pass. The most common example is sp3 carbon, but there are other judgment calls that can also be made about when an atom is considered "blocking".

The document then offers some graphical examples with electron delocalization islands in gray:

Confusingly, the same concept also appears to go by other names, including "dot paths" and "islands of resonance:"

The first stage of creating the coordination layer involves processing the molecule by distilling the atom and bond properties into a limited form. When valence counting rules are applied to a hydrogen-suppressed organic structure, having bond orders, charges, radicals and hydrogen counts is an overspecification: one or two of these properties can be removed with most information still intact. The standard InChI algorihm [sic] emits a graph that lacks bond order and radical status, but includes charges and hydrogens. The "DotPath" algorithm takes a similar approach, except that it takes into account the fact that the realm of inorganic chemistry does not provide for any reasonable set of rules to localise charges on specific atoms. It is, however, possible to identify "islands of resonance" within graph components, sum up the formal charges within each of these islands, and treat the charge as being delocalised within that scope.

Although the document doesn't describe the algorithm for finding electron delocalization islands in detail, the texts hint at how this might be accomplished. An implementation can be found within a separate source code repository. A working demonstration of the dot path algorithm is available online.

Electron delocalization islands may bring to mind a related concept: Kekulé structures and aromaticity. An aromatic bond is a multi-atom arrangement that can only be represented as a superposition of valence bonds. To address this problem, the aromatic bond is "Kekulized" to yield a single arbitrary Kekulé form consisting of only two-centered bonds. The Kekulé form makes it possible to deal with aromatic bonding at the expense of introducing artificial asymmetry. In a similar way, zero-order bonds could allow file formats and toolkits to work with organometallics, but at the cost of introducing artificial asymmetry, and possibly rendering the concepts of bond order and formal charge meaningless.

Bonding System

Electron delocalization islands bear a striking similarity to a concept known as bonding system first described by Andreas Dietz in his paper Yet Another Representation of Molecular Structure.

In a nutshell, a bonding system is a connected molecular subgraph of degree two or higher with an associated electron count attribute. In other words, a bond is merely a special case of a bonding system, but restricted to a single edge. Bonding systems generalize the traditional two-atom bond to multiple atoms. Fractional bond orders and formal charges fall out naturally from a suitably configured molecular graph. Organometallics, inorganics, mesomers, and tautomers can all be handled by a single, uniform abstraction, with no need to identify or separately treat special cases.

Given a molecular graph with atomic attributes and all bonding systems, the exact formal charge for any atom and the exact formal bond order across any edge can be computed. The computation is described in detail in both Dietz's paper and my writeup.

The main tradeoff when using bonding systems is complexity. Representation is more complex because bonding systems have many edges rather than just one. Analysis is more complex because calculations of formal charge, valence, and bond order need to account for the possibility of multi-atom bonding systems.

In practice, I've developed an optimization that eliminates a lot of the complexity. A molecular API can be crafted that simplifies implementation for traditional bonds while hiding the fact that this optimization has taken place.

Outlook

Perhaps the biggest headwind facing any attempt to upgrade molecular representation is inertia. Chemists must be made aware of the problem and how it affects them. Toolkit vendors must recognize the problem and move to address it. Algorithms previously written for two-centered non-dative bonds need to be upgraded. End user tools must change the ways that user interfaces work. Change is never easy, and the status quo has served chemistry well over the years.

Even so, a growing number of chemists understand the problem and are starting to take steps to address it. The work on zero-order bonds speaks to this, as do the 20+ chemists in attendance at the last InChI working group on organometallics in April.

Conclusion

The Zero-Order Bond (ZOB) proposal offer a pragmatic solution to the problem of accurately encoding extended bonding arrangements. To the extent that the idea can be retrofitted onto current tools and practices, ZOB may eventually gain widespread adoption, at least incrementally. Zero-order bonds could also serve as a bridge between today's molecular representations and more generalized representations, such as those based on bonding systems that offer greater expressiveness.