Running InChI Anywhere with WebAssembly

At the recent NIH Virtual Workshop on InChI, I gave a talk titled Running InChI Anywhere with WebAssembly. This article expands some of the major points and answers a couple of questions I got.

WebAssembly is a Big Deal

Although it's flown under the radar for years, WebAssembly (aka Wasm) is a big deal. No matter what kind of software you write or run on a regular basis, WebAssembly will likely become an important part of the way you work.

High-performance, compiled languages like C, C++, and FORTRAN have dominated software development in computational chemistry and cheminformatics for decades. This has left a rich foundation of legacy code in its wake. The scale of some of this software makes it effectively irreplaceable. Some may be put off by the use of the term "legacy software." It's a badge of honor to me. Legacy software is software that's proven itself and stood the test of time. It's stuck around because it was good enough in the first place.

InChI is a good example. The first version (1.01) was released in 2006. The source code weighs in at over 160,000 lines, most of it C. Importantly, it just works. Judging from the participation at the NIH InChI workshop, dozens of research groups rely on InChI on a daily basis for some mission-critical aspect of what they do. WebAssembly offers a way to markedly expand the kinds of applications that a tool like InChI can be used to build.

WebAssembly is a portable compile target and fast execution environment. Packages like InChI can be compiled to WebAssembly and run anywhere with a runtime. This may sound like the "Write Once, Run Anywhere" promise from Java's early days. The main difference is that there's no heavy runtime to lug around, nor is WebAssembly tied to any particular language. Bring your language of choice, compile to WebAssembly, and enjoy near-native performance across devices and more importantly, environments.

The most important environment WebAssembly runs on is the web browser. Since 2017, all major Web browsers support WebAssembly 1.0 in its entirety. WebAssembly became a W3C recommendation in 2019. The scale of the efforts around WebAssembly today is very large. The implications can't be overstated. JavaScript and WebAssembly are now the browser's only two software deployment targets. And WebAssembly is likely to assume an ever-expanding role as the target when performance or non-JavaScript language support is key.

But there's more, because WebAssembly support has landed in all major programming languages. That support often takes the form of a runtime that executes WebAssembly binaries. But increasingly it extends to the language itself being compilable to Wasm.

InChI Compiles to WebAssembly

Over the course of several months of part-time effort, I developed a reliable method to compile InChI to WebAssembly. This system is called InChI-Wasm. I've documented some of the work leading to InChI-Wasm in these articles:

- Compiling InChI to WebAssembly Part 2: From Molfile to InChI

- Compiling InChI to WebAssembly Part 1: Hello InChI

- First Steps in WebAssembly: Hello World

- Compiling C to WebAssembly and Running It - without Emscripten

This system was created with maintainability and flexibility in mind. The InChI source files themselves are not changed in any way. This loose coupling means that InChI itself can be treated as just another plugin. Updates to InChI should be easy, as was demonstrated by my recent upgrade from InChI v1.05 to InChI v1.06. Less obviously, maintainability and flexibility are supported by avoiding the reams of glue code and extraneous tools often emitted by tools like Emscripten.

The system consists of four components:

- A C Wrapper. Its purpose is to define an interface through which the InChI Wasm binary can communicate with the outside world.

- InChI Sources. These are used verbatim as received from IUPAC. In practical terms, they're included as a Git submodule.

- A Build Script. This is nothing more than a bunch of flags passed to the compiler.

- The LLVM Compiler. Also known as

clang, this compiler produces a*.wasmfile that can be executed on any WebAssembly runtime.

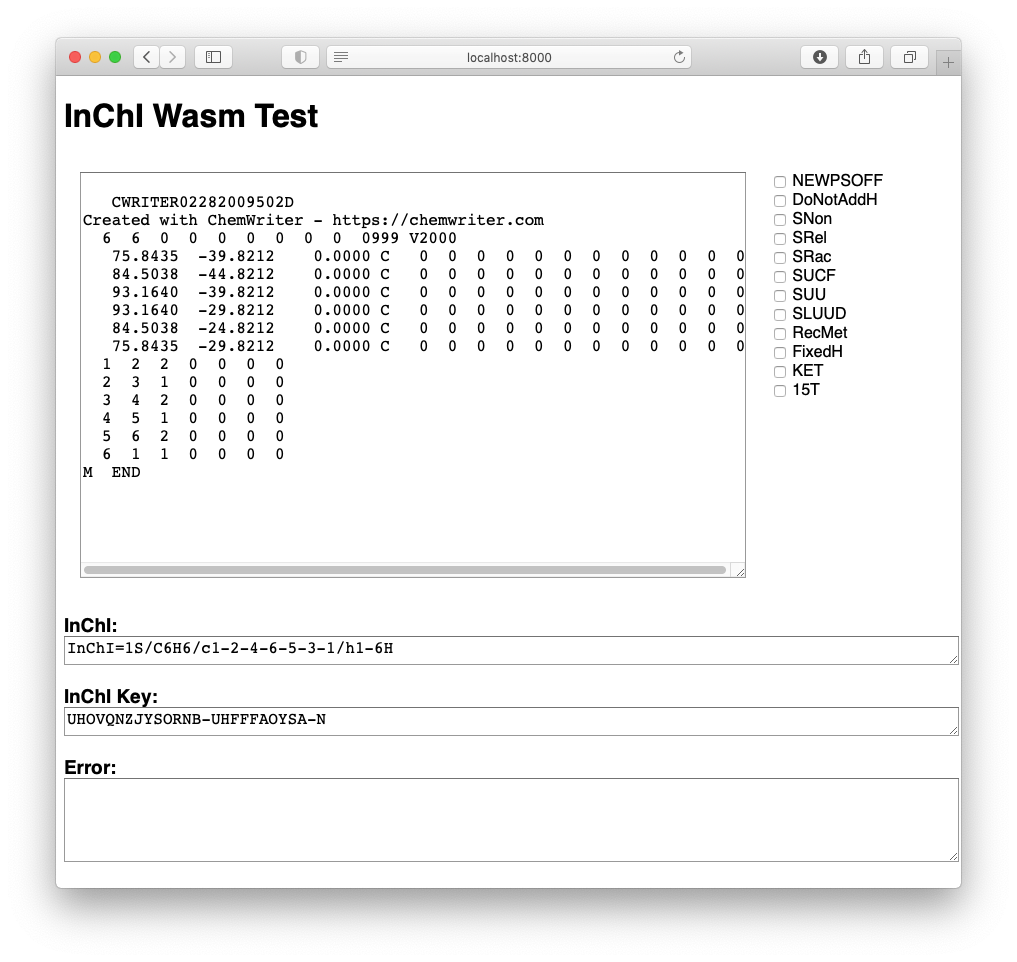

The InChI-Wasm project is hosted on GitHub. Its distribution directory (dist) contains a working HTML demonstration that can be run in any Web browser.

Near-Native Speed

Performance has been a central consideration for WebAssembly from the beginning. There are many claims as the performance once can expect from code compiled to Wasm, including one made by the WebAssembly project homepage itself:

WebAssembly aims to execute at native speed by taking advantage of common hardware capabilities available on a wide range of platforms. [my emphasis]

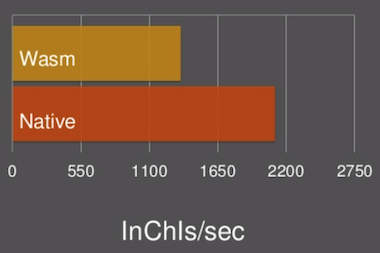

I tested this claim with a benchmark. In an apples-to-apples comparison, the WebAssembly version of InChI yields run times within a factor of two of native speed. That's plenty fast for many applications.

This benchmark was run against the most recent SureCHEMBL update of about 114K records. Each record contains a molfile and an InChI, allowing the performance benchmark to serve double duty as a validation suite.

I should probably have made a disclaimer about benchmarks in my talk. The usual caveats apply. Benchmarks are hard. Benchmarks can be misleading. Benchmarks don't always compare apples-to-apples even when it seems like they do. That said, I tried to the extent that technology allows to make an apples-to-apples comparison. Have a look at the code and judge for yourself.

To create a level playing field, the benchmark was designed to run in Node.js. By swapping the flags passed to the LLVM compiler, two different InChI executables were built: one Wasm and the other native (macOS). Depending on the flag passed to the benchmark, one or the other of these executables is run within Node.js. To run each version, the benchmark uses the appropriate data transfer method. Performance differences reflect differences in the speed of execution of both Wasm vs native InChI, as well as the data transfer method into and out of the InChI binary.

Rethinking the Web Browser

There's a tendency to view the Web browser as a dumb data terminal. It receives data from a server, renders a view of it, and makes some simple requests. Even with all of the things that modern browsers are capable of such as hardware-accelerated 3D graphics, fast software execution, the best UI development platform in existence, broad compatibility across implementations, and near-universal deployment, this perception persists.

My talk highlighted two projects that challenge this view:

- Wikipedia Chemical Data Explorer. Interactively draw structure queries to fetch data from Wikipedia about the corresponding substances.

- Pyodide. Jupyter notebooks within the browser. Compiles an entire Python Notebook system, including dependencies, to Wasm. Eliminates the need for a server, which can be useful in some cases.

Software developers tend to vastly underestimate the difficulty non-techical users have with installing software. A few months back I published an article talking about how to set up a Jupyter environment. Unfortunately, the average chemist will not jump through those kinds of hoops to run your software. It's just not happening.

I could have included half a dozen examples in addition to the two I cited. The point is that that Web browser is the most sophisticated software deployment platform ever created. And it's the one option that requires zero work on the part of your audience. Using the browser as a dumb data terminal throws away a golden opportunity to create something that can improve the way that chemists use software. Not five years in the future, but today.

Permissionless Systems

Steve Heller kicked off the NIH symposium by talking about the origin of the InChI project. Some time ago, his work involved curating a database that used Chemical Abstracts Service (CAS) registry numbers. After initially smooth sailing, disagreement arose around permission to access the service. Eventually, this disagreement became untenable, motivating Steve to start the InChI project.

At its core, InChI serves the role of a molecular key, just like the CAS Registry. What sets InChI apart is its permissionless design. Whether I use InChI or not, I don't need to involve Steve Heller, NIH, NIST, EPA, the American Chemical Society, or any other organization. Now, try saying that about Chemical Abstracts Service and the CAS Registry.

Permissionless systems are revolutionary and they're subversive. They're revolutionary because the give power to individuals. They're subversive because they have little use for gatekeepers.

But permission and granters of permission have a way of sneaking up on you. For example, one workaround for being unable to run native code within a Web browser is to deploy the software to a server. Doing so, however, creates a permission relationship. Without access to the server, users can't run the service. If you maintain such a service, you'll find yourself granting and refusing permission sooner or later.

WebAssembly offers a way out of this anti-pattern. Yes, you'll need a server to distribute the static assets like HTMl, CSS, JavaScript, and Wasm comprising your application. But that's a very low bar compared to hosting a Web server running an InChI service. Running Web services, particularly services accepting untrusted input while invoking code compiled natively from unsafe languages, presents a high barrier from the perspective of entry, maintenance, and security.

Conclusion

For all of its current capabilities, WebAssembly is a young technology. The 1.0 release being used today is considered an MVP (Minimum Viable Product). Efforts are now underway to expand WebAssembly's capabilities still further. The outcome is clear, at least to me. WebAssembly will become an essential technology and could change many current software development practices. It will give rise to new ways of writing and distributing software, and maybe new kinds of applications. The InChI-Wasm project demonstrates one way to expand the reach of legacy cheminformatics/computational chemistry software through WebAssembly. It's not hard to imagine this pattern repeating itself.

Summary image credit: Wikipedia