First Steps in WebAssembly: Hello World

WebAssembly (aka Wasm) is a new W3C recommendation and the second target language to be supported by all browsers. WebAssembly is also fast becoming a full-blown runtime environment outside the browser. Unlike JavaScript, WebAssembly was designed with fast execution in mind. A previous article described how to compile C directly to WebAssembly. That's great if Wasm only matters to you as a compile target, but if your aim is to understand WebAssembly itself and how it interacts with JavaScript, a more fundamental approach works better.

One way to begin learning a new language is to write a Hello World. Although such programs exist for WebAssembly (for example, see this one), in most cases, they don't actually print the text "Hello, World!". This article takes a different approach that not only prints the text, but also illustrates the powerful technique of invoking JavaScript functions from WebAssembly. For more detail, see the article on MDN.

Prerequisites

You can complete this tutorial with as little as two non-ubiquitous pieces of software: Visual Studio Code (aka VS Code) and its WebAssembly Plugin.

Alternatively, you can dispense with even these modest requirements and run the example code directly from Node.js as described near the end of this article.

Components

The most common scenario today has WebAssembly running in a browser. This may change in the future, but for now this tutorial assumes your goal is browser deployment. Three files are required, which you should create and place into the same directory:

index.htmlA boilerplate html file with a singlescripttag.hello.jsA JavaScript file that sets up the environment in which WebAssembly will run.hello.watA file containing a human-readable form of WebAssembly.

A fourth file, hello.wasm will be translated from hello.wat by VS Code.

index.html

Save the following html as index.html:

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html lang="en">

<head>

<meta charset="UTF-8">

<title>Hello, World! in WebAssembly</title>

</head>

<body>

<script src="hello.js" type="module"></script>

</body>

</html>

Using the type module for the script tag ensures that values in hello.js won't pollute the global namespace.

hello.js

Running WebAssembly in browsers requires the creation of an environment. Currently, this can only be done through JavaScript. Save the following Wasm configuration code as hello.js:

const memory = new WebAssembly.Memory({ initial: 1 });

const log = (offset, length) => {

const bytes = new Uint8Array(memory.buffer, offset, length);

const string = new TextDecoder('utf8').decode(bytes);

console.log(string);

};

(async () => {

const response = await fetch('./hello.wasm');

const bytes = await response.arrayBuffer();

const { instance } = await WebAssembly.instantiate(bytes, {

env: { log, memory }

});

instance.exports.hello();

})();

The most application-specific part of this file is the log function, which will be called from WebAssembly to print text to your browser's console. Using the the memory object, which will be shared between the JavaScript and WebAssembly code, log extracts bytes indicated by the parameters offset and length.

The JavaScript log function may seem like cheating, but there is currently no other way to print to the browser console. Wasm modules aren't allowed to directly interact with the browser console or DOM. These services can only be accessed indirectly through a JavaScript function call.

The async block at the end of hello.js supplies the infrastructure needed to configure WebAssembly and use its exported functions. The memory object and log function are injected into the WebAssembly environment via the object literal passed to WebAssembly.instantiate. Although many tutorials use promises to load and process Wasm, I find an anonymous async function to be clearer. The trailing empty parentheses are required to complete the IIFE pattern.

hello.wat

Finally, we arrive at the main course. WebAssembly Text Format (WAT) is a human-readable 1:1 transformation of WebAssembly. As such it can be used to generate executable .wasm files. Add the following text to hello.wat:

(module

(import "env" "memory" (memory 1))

(import "env" "log" (func $log (param i32 i32)))

(data (i32.const 0) "Hello, World!")

(func (export "hello")

i32.const 0

i32.const 13

call $log

)

)

Before diving into this example, it may be useful to take a few steps back to discuss WebAssembly in a more general sense.

The parentheses give WAT a very Lisp-y feel. The reason is that both Lisp and WAT represent syntax trees with a versatile notation called s-expressions. Parentheses wrap a whitespace-delimited list of child nodes, and nesting is supported.

For example, the simplest Wasm module, containing a single node is:

(module)

This module could be made more useful by adding a callable function that answers the ultimate question, like so:

(module ;; start of module

(func (export "answer") (result i32) ;; begin function

i32.const 42 ;; push the answer (42) onto the stack

) ;; end of function

) ;; end of module

The central abstraction in WebAssembly is the "stack," a ubiquitous construct in low-level programming. Operators push values onto and pop values off of the top of the stack. Values appearing on the stack when a function exits will be returned to the caller. Any returned values must be declared by a WebAssembly function. The above example does this with the result expression.

Getting back to hello.wat, the first two lines import the dependencies created on the JavaScript side. WebAssembly uses a two-level hierarchy for the import namespace. The names for each level can be arbitrary, but both must be present. The memory object and the log function are both imported as children of the env object. An import can optionally be named for later reference (as with log), but a type declaration is mandatory.

Recapping the interaction between WebAssembly and JavaScript, the JavaScript object literal that created the import was:

{

env: { memory, log }

}

And the WebAssembly import looks like this:

(import "env" "memory" (memory 1))

(import "env" "log" (func $log (param i32 i32)))

The last expression in hello.wat exports a function called hello. Once exported, the function can be called by another WebAssembly function, or from JavaScript. Within the function, two values are pushed sequentially (0, and 13). The first is an offset to the shared memory defined on the JavaScript side (0). The second is the length of the "Hello, World!" string (13). The call operator pops the two values from the stack and invokes the named function log with them. Nothing is left on the stack, so the function returns no values.

(func (export "hello")

i32.const 0

i32.const 13

call $log

)

Between the import and export section is a single line of code that writes the text "Hello, World!" starting at memory index 0 using the data operator. A similar data service exists for most executable binary formats.

(data (i32.const 0) "Hello, World!")

To summarize, three things happen when the Wasm module is loaded:

- Imports expose the

memoryandlogobjects created in JavaScript. - The bytes representing the text "Hello, World!" are written to shared memory starting at index 0.

- A function called

hellois exported. This function invokeslog, passing theoffsetandlengthparameters.

Program flow takes place in three steps after initialization:

- JavaScript calls the exported Wasm

hellofunction. - Wasm invokes the JavaScript

logfunction, passingoffsetandlengthparameters. - JavaScript reads shared memory to construct a string, which is then printed to the console.

hello.wasm

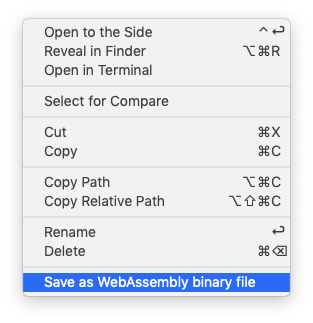

You can translate hello.wat to hello.wasm with a number of tools. A convenient option is VSCode's WebAssembly Plugin. Right-click on hello.wasm and select the option "Save as WebAssembly binary file." Use hello.wasm as the file name.

Execution

If you try to open index.html directly from your file system you're likely to receive an error involving "Access-Control-Allow-Origin." It can be eliminated by loading the file from a local server. A convenient option is Python's SimpleHTTPServer. Start it with:

python -m SimpleHTTPServer

The default port is 8000, so loading localhost:8000 with an open browser console should produce the text "Hello, World!".

Bonus: Execute from Node.js

WebAssembly can also be run directly from Node.js with the inline-webassembly module. The code below mirrors the HTML tutorial, but dispenses with the need for additional files or a local Web server.

const iw = require('inline-webassembly');

const memory = new WebAssembly.Memory({ initial: 1 });

const log = (offset, length) => {

const bytes = new Uint8Array(memory.buffer, offset, length);

const string = new TextDecoder('utf8').decode(bytes);

console.log(string);

};

(async () => {

const wasm = await iw(`

(module

(import "env" "memory" (memory 1))

(import "env" "log" (func $log (param i32 i32)))

(data (i32.const 0) "Hello, World!")

(func (export "hello")

i32.const 0

i32.const 13

call $log

)

)`, {

env: { log, memory }

});

wasm.hello();

})();

Conclusion

WebAssembly is a promising and versatile technology that's still in its proof-of-concept phase, but nevertheless deployed widely. The simple Hello, World program presented here offers a good starting point for a variety of WebAssembly explorations.