A Brief Introduction to Graph Convolutional Networks

The extensive use of graphs in chemistry to model both reactions and molecules creates challenges for machine learning. Most of the previous and ongoing research in the field solves the problem by translating molecular graphs into forms that fit cleanly within existing paradigms and tools: images; text; and binary fingerprints. Graph representations themselves seem out-of-place at first.

However, it's possible to work with graph representations more directly using Graph Convolutional Networks (GCNs). This article gives a quick introduction to the idea.

Circular Fingerprints

If you're familiar with extended connectivity fingerprints (aka ECFP or "circular fingerprints") or Morgan's algorithm on which circular fingerprints are based, then graph convolutional networks will seem familiar. A circular fingerprint is a set of feature vectors in which each member represents an atom in a molecule.

An ECFP is characterized by its diameter of perception, or double the length of the shortest path between the focal atom and the atoms augmenting the feature vector. The simplest form, ECFP_0, disregards neighboring atoms. Its feature vectors would include individual atomic properties only such as: atomic number; isotope; degree; charge; and unsaturation. The next level, ECFP_2, sums the feature vectors of immediate neighbors with that of the central atom. ECFP_4 does the same, but for two layers of neighbors, and so on.

With each increase in the radius of perception, the atomic feature vectors of a circular fingerprint include more information about the rest of the molecule.

Message Passing

Graph neural networks work on a similar principle called message passing. The procedure can be thought of as working through matrix operations. Given a graph with N nodes, the inputs to a GCN are:

- An NxF0 feature matrix X, where F0 is the number of initial node features; and

- An NxN adjacency matrix.

Each layer of the GCN defines a propagation rule, also in the form of a matrix. The propagation rule determines how inputs will be transformed before being sent to the next layer. Propagation rules can take many forms. The simplest does little more than multiply the incoming feature matrix by the adjacency matrix.

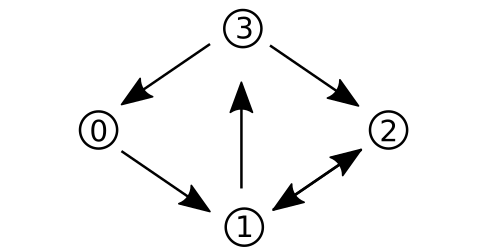

For example, consider the following directed graph G:

It can be represented by the adjacency matrix A:

0 1 0 0

0 0 1 1

0 1 0 0

1 0 1 0

A simple feature matrix might be composed of an ordered pair consisting of the node's index and a label equal to the additive inverse of this index. We could represent this as the following feature matrix X:

0 0

1 -1

2 -2

3 -3

Imagine our propagation rule is to simply multiply A by X. Doing so yields:

1 -1

5 -5

1 -1

2 -2

Notice how the resulting matix is the same one we'd construct if asked to report the sum of indices for neighboring nodes in the first column and the sum of weights for neighboring nodes in the second column. Multiplying the resulting matrix again by A would give a result that included information about features one node more distant. And so on.

Although this approach is too simple by itself to yield anything useful computationally, it does illuatrate how the message passing idea can be reduced to practice through matrix arithmetic. For more, see the excellent introduction How to do Deep Learning on Graphs with Graph Convolutional Networks.

A related presentation from Microsoft is also worth watching.

Conclusion

Message passing bears a striking similarity to Morgan's algorithm and the construction of circular fingerprints. The process forms the basis of Graph Convolutional Networks, a powerful method for using graphs in machine learning.