Chemical Line Notations for Deep Learning: DeepSMILES and Beyond

Last year marked the 30th anniversary of David Weininger's SMILES paper. Although the computing landscape has changed beyond recognition since 1988, the SMILES language has barely changed at all. Sure, there's the alternative line notation InChI and the OpenSMILES specification. But the former hasn't changed SMILES itself, and the latter has mainly narrowed the range of SMILES formulations seen in the wild. New SMILES language features that break backward compatibility, although they do exist, remain mostly a niche.

This article takes a look at DeepSMILES, a line notation based on SMILES. Intended to fill a gap in deep learning tools, DeepSMILES' streamlined syntax could find other applications as well. More than this, DeepSMILES raises the question of what an ideal molecular language for deep learning might look like.

DeepSMILES in a Nutshell

DeepSMILES distinguishes itself from SMILES in two respects:

- ring closures use only one set of ring-closure numbers (rnums); and

- the left parentheses character (

() is not used.

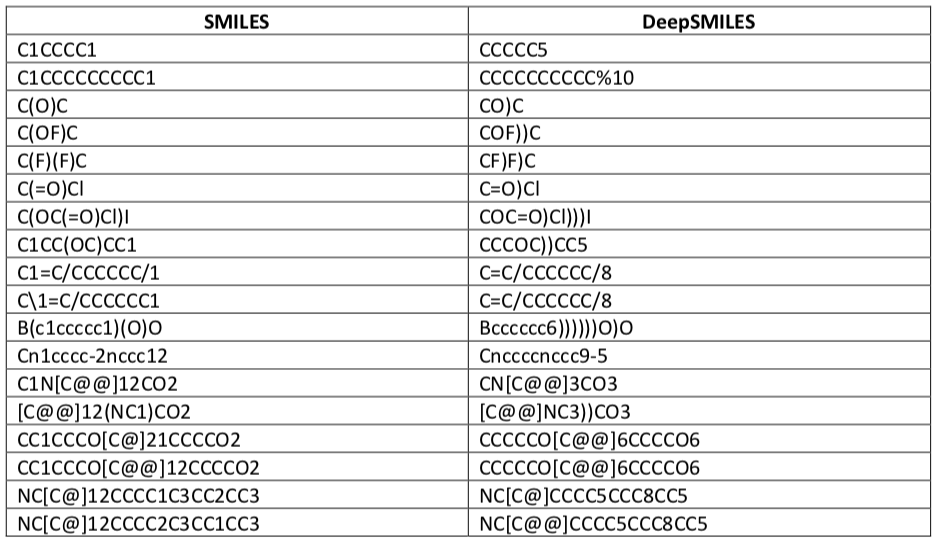

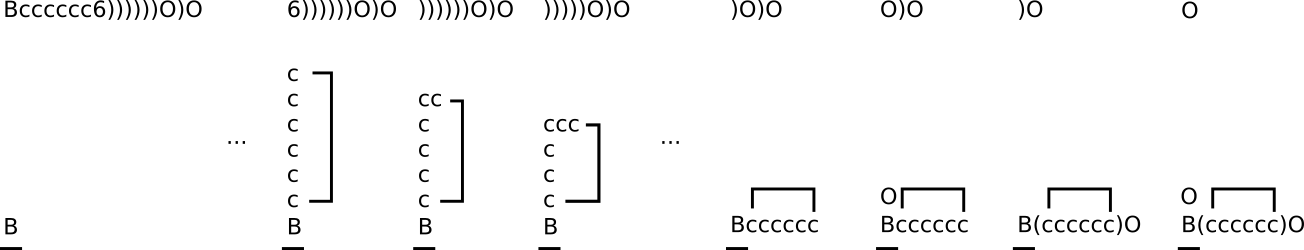

These syntax changes require some semantic adjustments. Other than that, DeepSMILES and SMILES are identical. The following chart, taken from the DeepSMILES paper, gives some examples.

The goal is simplification by eliminating balanced tokens. Whereas SMILES encodes rings as a balanced pair of ring opening and ring closing symbols, DeepSMILES uses a single postfix rnum denoting the size of the ring being closed. Ring sizes larger than nine members are supported with %XX notation. As a simple example, consider the respective SMILES and DeepSMILES for benzene:

c1ccccc1(SMILES)cccccc6(DeepSMILES)

Not only does this difference simplify DeepSMILES, but DeepSMILES automatically reveals the size of any ring.

A more wide-ranging change can be seen in DeepSMILES' approach to branching. SMILES uses balanced parentheses to denote a branch. Everything within the parentheses is part of a branch, and nesting is allowed. Without a left parentheses character, DeepSMILES needs a different way.

The solution comes by way of a stack. Fortunately, a DeepSMILES reader only needs to follow two branching rules when using the stack:

- each new atom token encountered in the left-to-right processing of a SMILES string causes the corresponding atom to be bonded to the top stack element (if available) and then pushed; and

- on encountering a right parentheses character (

)), the stack is popped.

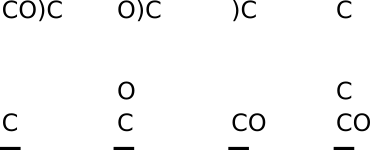

Consider the DeepSMILES string CO)C, which corresponds to the SMILES C(O)C. Reading the first atom symbol, "C", causes a carbon atom to be pushed to the stack. Reading the second atom symbol, "O", causes an oxygen atom, connected to the preceding carbon by a single bond, to be pushed to the stack. Reading the closing parentheses symbol ) causes the top atom (oxygen) to be popped from the stack. Reading the last atom symbol "C" causes a second carbon atom to be pushed to the stack, connected to the next carbon atom down by a single bond.

A more complicated example can be seen with the DeepSMILES Bcccccc6))))))O)O (below). Six sequential right parentheses are used to pop the stack back to the original boron atom. Ring closures, like all other bonding arrangements, survive stack popping operations.

A command-line utility for the interconversion of SMILES and DeepSMILES is available from GitHub.

Additional points to consider include:

- An invalid DeepSMILES will be generated if too few atoms precede the ring size. For example, the string

CC9would not be a valid DeepSMILES. - The ring closure digit refers to the size, in atoms, of the ring — not a location within the DeepSMILES string. The matching ring closure atom must be found by walking the graph under construction.

- Because only one ring token is available, the atom and bond preceding it must carry conformational, configurational, and bond order information.

- If two ring sizes appear adjacent to each other, either the second must use an explicit bond order (even if single) as a separator, or it must use percent ("%") rnum notation.

- Some SMILES->DeepSMILES conversions aren't possible (e.g.,

CC(C1)CCCC1), however this style is not common. - Brackets must still be balanced. Bracket atoms can be found in numerous compounds such as secondary pyrroles and indoles, as well as stereocenters. However, brackets never nest, which should make their encoding simpler.

SMILES in Deep Learning

DeepSMILES will likely benefit only those studies in which line notations directly interact with a neural network. For example, converting line notations to another representation (such as a circular fingerprint or image) prior to processing by a classifier cancels most of the potential benefit.

During training, a neural network constructs a model for its input data. That model must capture everything about the training set, including its encoding method. It seems reasonable that a network can perform better given the simplest possible encoding method for input data. Therefore, a better use for DeepSMILES would be in classifiers that accept SMILES directly as input.

An even more intriguing application would bea generative neural network that writes line notations directly. Generative machine learning tools are capable of not just classifying or scoring examples, but in producing new examples. A flurry of activity around this approach has appeared in the last four years.

The idea that a neural network could be trained to generate SMILES strings appears to trace its roots to a 2015 study by Google. In it, a neural network was described that was capable of generating valid English sentences from a training corpus.

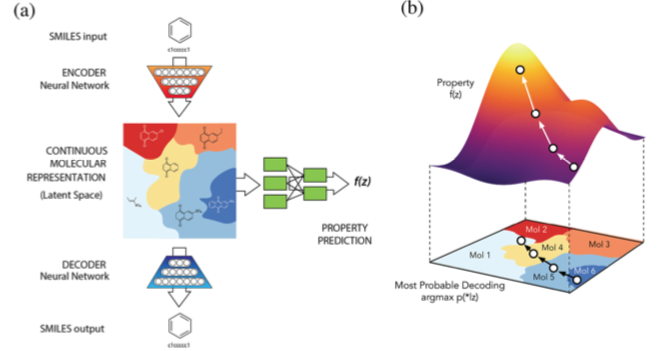

The centerpiece of this work was a kind of neural network known as a variational autoencoder (VAE). A previous post discussed the structure of neural networks at a high level. To recap, a neural network can be thought of as a directed graph consisting of at least two layers of nodes: input and output. One or more optional "hidden" layers may sit between these two layers.

A variational autoencoder (VAE) is a specialized neural network containing a hidden layer known as a "bottleneck." Whereas input and output layers contain the same number of nodes, the bottleneck layer contains fewer nodes. This constriction limits the dimensionality with which a model can be represented, leading to a form of compression. In this way the network is challenged to produce an efficient model of the training set.

A VAE capable of surmounting the resource constraints imposed by the bottleneck can be applied to problems such as compression and noise reduction. However, these problems already have good solutions. A much more interesting direction applies a VAE to the problem of generating output data that mimics its training data.

SMILES Autoencoders

In 2017 a team led by Alań Aspuru-Guzik described an adaptation of the Google work to SMILES strings. In a thought-provoking twist, the team augmented the VAE with layers to be trained on calculated chemical properties: logP; Synthetic Accessibility Score (SAS); and Quantitative Estimation of Drug-Likeness (QED). The authors found that the network not only generated valid SMILES, but also tended to made good property predictions.

The authors say surprisingly little about invalid SMILES generated by the network, but do note:

The character-by-character nature of the SMILES representation and the fragility of its internal syntax (opening and closing cycles and branches, allowed valences, etc.) can still result in the output of invalid molecules from the decoder, even with the variational constraint. When converting a molecule from a latent representation to a molecule, the decoder model samples a string from the probability distribution over characters in each position generated by its final layer. As such, multiple SMILES strings are possible from a single latent space representation. We employed the open source cheminformatics suite RDKit to validate the chemical structures of output molecules and discard invalid ones. While it would be more efficient to limit the autoencoder to generate only valid strings, this postprocessing step is lightweight and allows for greater flexibility in the autoencoder to learn the architecture of the SMILES.

In other words, invalid SMILES were generated, but they were filtered after the event. It seems reasonable to suspect that a molecular encoding designed specifically with generative machine learning in mind might allow better resource allocation and therefore better performance. The authors hint that this might indeed be the case:

We also tested InChI as an alternative string representation, but found it to perform substantially worse than SMILES, presumably due to a more complex syntax that includes counting and arithmetic.

Since the publication of the work by Aspuru-Guzik and coworkers, at least 20 studies using the basic idea have been published. In addition to VAEs, deep recurrent networks (RNNs) have also been used to generate SMILES for molecules having desired properties, as exemplified by Ertl and coworkers.

To date, one study has used DeepSMILES. Unfortunately, this doesn't provide the kind of apples-to-apples comparison with previous work I'd like to see, but rather uses DeepSMILES to encode protein targets while indirectly using SMILES to encode ligands.

Alternative Line Notations for Machine Learning

The DeepSMILES paper ends with some thought-provoking questions:

… it is worth considering whether if one were to design from scratch a linear notation for molecules for use in Deep Neural Networks, that syntax would be SMILES, DeepSMILES, or indeed a variant of one of the other chemical line notations. What are the features of these strings that aid learning the underlying chemical structure, and what are those that hinder? Perhaps the perfect notation would be one where (1) every string represents a valid molecular structure, (2) there are few duplicate representations, (3) small changes in the string tend to result in small changes to the structure (and vice versa) and (4) string size is related to pharmaceutical usefulness or synthetic accessibility.

What are the qualities of a good machine learning line notation? Do any of the currently available line notations fit the bill? Two possibilities not specifically mentioned in the paper are:

- IUPAC nomenclature

- Wisswesser Line Notation (WLN)

Whereas SMILES builds molecules atom-by-atom, IUPAC nomenclature and WLN build molecules from fragments. These fragments have been specifically selected for their widespread distribution in compound collections. It's not hard to imagine that a neural network could be efficiently trained to recognize and compose these kinds of line notations. Depending on how they're chosen, multi-atom fragments bear a much closer relationship to the "words" of a chemical language than bare atoms. WLN has the added advantage of generally requiring none of the balancing constructs or locants used in IUPAC nomenclature.

There is, however, one critical problem with both options: software support. In contrast to SMILES, which enjoys nearly universal support among cheminformatics toolkits, IUPAC nomenclature is much less widely-supported. Readers and writers tend to be restricted to commercial packages. One notable exception is OPSIN, which can read IUPAC nomenclature. WLN, on the other hand, is not supported by any currently-used cheminformatics toolkit that I know of. And as these things tend to happen, WLN might be the more interesting possibility given its extremely simple syntax.

Still another option might be dispose of line notations altogether. Within the last year a handful of machine learning approaches have been described in which molecular graphs are used directly. Such approaches do away with string molecular representations altogether, although at the cost of requiring custom tooling. For an example, see MolGAN.

Conclusion

The method used to represent molecular structure can have far-reaching effects on the utility and flexibility of machine learning models developed from them. DeepSMILES offers a fascinating first step in the direction of molecular encoding schemes optimized for consumption and generation by neural networks. The field is wide open.