Clock Yourself

Fear of falling (FOF) is a major concern among the elderly. Depending on the source, between 21% and 85% of those living in care communities experience FOF. The condition is insidious due to its reinforcing mental and physical aspects. Fear of falling leads to reduced physical activity, which leads to weaker muscles and joints, and degraded coordination. These follow-on effects increase fall risk, setting up a feedback loop. Once FOF sets in, it can become very hard to break free of the resulting downward spiral.

I don't consider myself elderly, but I know more than others my age about FOF because I've lived it. This article discusses my personal experience with FOF and one tool I've found especially effective against it.

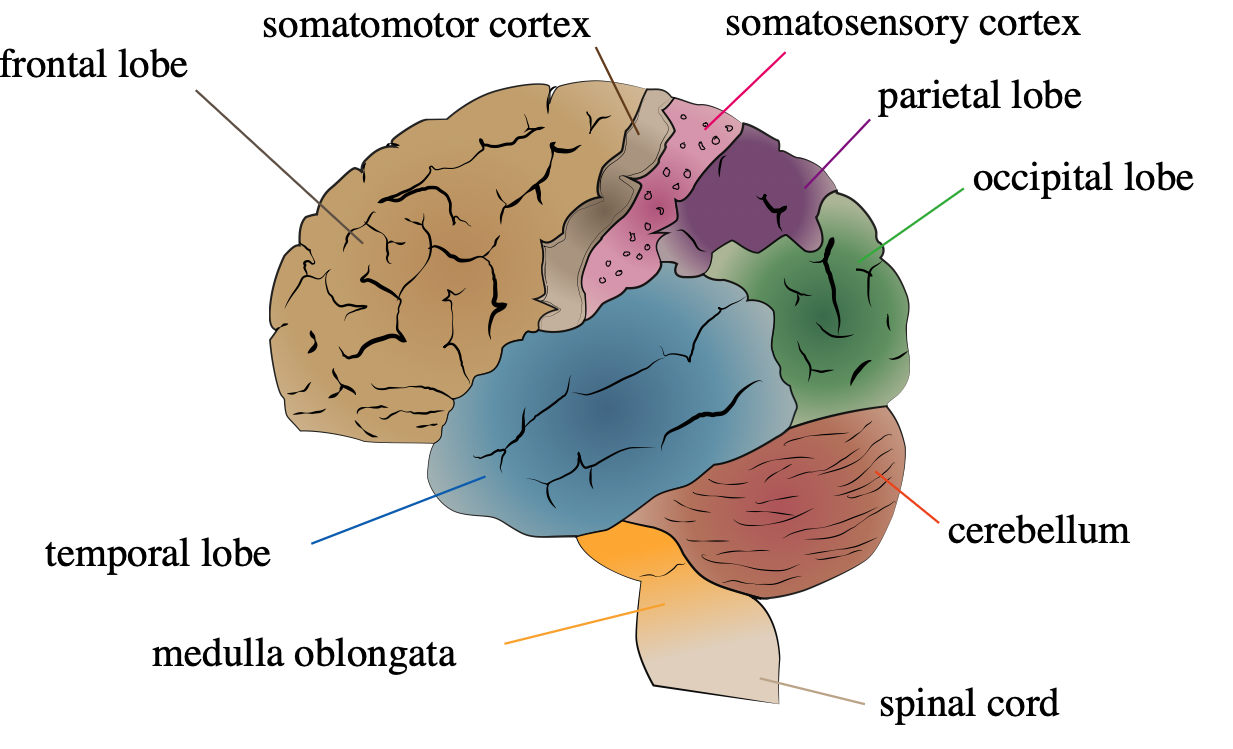

In March 2023 I was diagnosed with glioblastoma, a terminal form of brain cancer. Symptoms of this disease are linked to where the tumor occurs. Mine was centered in my right parietal lobe. This part of the brain integrates signals from other parts of the brain and plays a role in executive function. But the tumor was also just behind the right motor cortex, which controls left-side movement.

Surgery to remove the tumor went well, but my recovery was plagued by cognitive and physical impairments. This is a bad combination under any circumstances in that the patient may not recognize the loss of physical ability. But the combination is especially bad when it appears suddenly as it did with me. I was blindsided by what had happened, so I continued to act like I did before the operation.

The inevitable result of my sudden mental and physical decline was a fall, with my head hitting the floor of my hospital room — hard. This may not sound like a big deal given that I'm not elderly, but it was a terrible experience. It was scarier than anything I'd experienced to that point, including brain surgery. My body had refused the most elementary command and something I'd done thousands of times before. After I started falling, there was nothing I could do other than brace for impact. My immediate if aborted transport by gurney to the hospital's CT scanner confirmed that I wasn't the only one thinking that the fall may have done serious damage.

My medical report described the episode this way:

Patient found to be down in room after monitor alarming for sinus tachycardia. Per patient he was ambulating in room with walker after getting up from chair unassisted and his walker then got caught and he tripped and fell to his left side, striking his head on the floor. Abrasion and contusion noted to left head, no other sxs of trauma noted. Neuro exam unchanged and vitals stable, see flowsheets. Patient assisted back into bed for further assessment and treatment. Dr. [redacted] paged to bedside and assessed patient. Patient taken to CT scan however CT scan canceled after Dr. [redacted] discussed case with Dr. [redacted]. Patient returned to room and educated on need to call for help before getting out of bed, patient verbalizes understanding. All fall precautions in place and call light in reach.

Beyond infection and pain, if there's one thing hospitals try to avoid it's falling patients. A patient who has fallen once is at risk for falling again. For this reason I was given the special treatment reserved for patients who have fallen. A large yellow sign hung in my room's window. It read "FALL RISK." I was fitted with a yellow bracelet that marked me as a patient prone to falls. The sign and bracelet caused concern on the part of staff whenever I tried to stand. Wherever I went, I was required to wear a "gait belt" held firmly by a staff member. This didn't matter much because it instantly became difficult to get staff to walk with me. When staff did help me get up or walk, I could see the apprehension in their eyes. Fear of falling doesn't just affect patients — it spills over into those who care for them and the institutions that coordinate their care.

My acute disabilities continued for months after surgery. During part of that time I lived at a rehabilitation center. My mobility was so bad and concern over fall risk so high that I'd been driven from the hospital to the rehab center by ambulance.

My reputation and the yellow wrist band preceded me to the new facility. The staff at the rehab wired my bed and chair with alarms that rang the nurse's station whenever I so much as shifted weight. My rapid descent from fully independent adult to something closer to toddler still haunts me.

Laying in bed or sitting most of the day wreaks havoc on the body through a process called deconditioning. Not only does the affected side become weaker, but so does the unaffected side. Even parts of the body with no connection to the injury can be affected. If left to continue the result is incapacitation of large muscle groups on both sides and in the core. Worse, reduced mobility can affect digestion and other bodily functions. From there it's just a matter of time before immobility and dependency snowball out of control.

Rehab had given me a lot of time to think. My biggest concern was to avoid another fall at home after my eventual discharge. I weighed around 190 lbs. My house had many internal stairs. Obstacles and tripping hazards were everywhere. Staff eyebrows rose whenever I described my living space. How was I going to avoid a repeat of my performance at the hospital?

The answer came from an unexpected source. I had started outpatient "speech therapy." From my time in rehab, I'd learned that speech therapy was code for cognitive evaluation and therapy. There were a lot of puzzles, few of which I could solve. One day the therapist I was working with introduced me to an app called Clock Yourself.

Clock Yourself consists a few dozen or so activities aimed at building physical and mental strength and agility. My speech therapist wanted me to use the app to build mental skill. But as I explored the app, it was one of its physical activities that grabbed my attention.

The activity, called just "Simple Clock," requires no equipment other than a phone. You start by standing on the floor with both feet together. You imagine yourself at the center of a clock laid flat on the floor with your feet at the center of the dial. One at a time, the app calls out a number from one to twelve, inclusive. You interpret the number as an hour. After the number is called you move either your right or left foot to that position on the clock while keeping the other foot planted on the dial's center. For example, if the number "one" is called, you bring your right foot to the one o'clock position. Then you return to a standing position with both feet together at the center of the dial. This continues until all numbers have been called in random order.

Simple Clock allows for a variety of speeds, durations, and progressions. I've been able to set just the right amount of stress over the time I've used the app.

Having performed this activity most days for the last year, I've learned some lessons. The first is that Clock Yourself was a powerful mental and physical workout disguised as a toy. My lower body strength and coordination had atrophied so badly that at first I could barely complete one minute at the lowest difficulty setting. The mental exhaustion I felt made sense, but still came as a surprise. My cognitive assessment had made it clear that I had a problem with clock faces. I couldn't read them. I couldn't draw them. And I couldn't reason about them. Clock Yourself allowed me to exercise this mental skill while building lower body strength and coordination. It was a workout for the mind and the body.

I took the mental and physical difficulty as a sign that Simple Clock was forcing me to practice skills that brain surgery had damaged.

The second lesson Simple Clock taught me was that if my center of mass suddenly shifted, I was capable of catching myself before falling. The Simple Clock workout builds the reflexes, strength, and flexibility needed to recover from surprises like this. I've seen this skill engage numerous times while walking outside or dodging obstacles around the house. I've even caught myself thinking "three" as I stepped to the the right to avoid a tripping hazard, or "twelve" as one foot snagged on a crack in the pavement, or "six" as I backed away from someone who suddenly stopped walking in the supermarket. I don't mentally register these numbers now because so much of the mobility I've regained has become automatic.

It's hard to overstate the positive effect this realization has had on my health. I'm under no illusions that I will never lose balance and fall. Rather, I've developed the skills to recover balance quickly before a fall occurs.

I also have a much better understanding of my limits than I did before starting Clock Yourself. If you're not walking because you're scared of a fall, there's no way to judge what you can and can't do. If every step has a surprising outcome, a fall is inevitable.

The greater comfort in difficult environments has led me to slowly build stamina walking up to several miles a day, some of it on uneven or even slippery surfaces. These activities have kept me out of bed during the day at the very least. More importantly, they've built strength and endurance that's allowed extended outdoor hikes and the improvement in quality of life that comes with that.

The most surprising lesson from using Clock Yourself/Simple Clock is that it can play a diagnostic role. I've noticed worse performance on this program as my condition has progressed. Past a point, no workout routine can overcome the damage caused by glioblastoma. Here, the utility lies in understanding what's happening, and what kinds of movements are likely to cause surprises. I think of it as one way to avoid trouble as my unpredictable condition runs its unstoppable course.