Round Two

In March 2023 I was diagnosed with glioblastoma, a form of brain cancer. According to the National Brain Tumor Society, about 15,000 Americans get the same diagnosis every year. Despite decades of research, untold millions spent, and hundreds of thousands of dead patients, the prognosis, measured in months to live, has barely budged. Public figures tend to keep their brain tumor diagnoses under wraps, but glioblastoma is thought to have killed Senators Ted Kennedy and John McCain, President Joe Biden's son Beau, billionaire Ted Forstmann, and six former members of the Philadelphia Phillies baseball team, among others. It doesn't matter how well-connected you are. It doesn't matter how much money you have. It doesn't matter how hard you pray to your God or gods. It doesn't matter how strongly you vow to "fight" it. From the moment that glioblastoma sinks its tendrils into your brain, you are marked for death. And that death is a gruesome affair, mutilating the brains of its victims while leaving distraught friends and families with little to do but watch while the person they once knew slides into a mental and/or physical abyss.

In the first article of this series, I quoted boxer Mike Tyson's famous line "Everyone has a plan until they get punched in the mouth." I still think this is a useful comparison. I led a comfortable life and I had plans. Then glioblastoma walked up and laid me flat on the pavement.

Now, according to my most recent MRI the tumor is back — with a vengeance. Round Two has begun.

The word "cancer" often conjures an image of a lump. If you must get cancer, a lump isn't such a bad thing relatively speaking. A surgeon can carefully carve around the lump, sparing healthy tissue while discarding the cancer. A surgeon who has performed a successful cancer surgery might summarize using the term "clear margins," meaning no cancer was detected around the boundary of the lump that was removed. A patient with a lump-like tumor removed with clear margins enjoys an excellent prognosis because there's nothing left to regrow. In some cases, more radical surgeries are feasible in which most or all of the affected organ is removed. Large volumes of healthy tissue can be sacrificed in the name of clear margins.

Glioblastoma isn't that kind of cancer. It's not a lump and so clear margins don't exist. To get a handle on why this is, consider a thought experiment in which you prepare a jello mold. As the mixture (a brain) is cooling in the refrigerator, pour a half cup of sand (glioblastoma) into the mold. Don't stir or mix. The next morning, turn the mold over onto a plate. Your job is to extract as much sand as you can while removing as little jello as possible. You can use only a spoon and a knife.

If you try to remove all of the sand, you'll take a lot of the jello with it. You've destroyed your patient's brain and they are dead on the operating table. But if any sand is left, the remnants will spawn more sand sooner or later. Your patient will be dead in a matter of months. If you try to compromise, your patient might recover, but with varying degrees of brain damage. And of course, the patient will die in a few months anyway as glioblastoma regrows from what was left behind.

The impossibility of pulling all the sand from the jello partly explains why every glioblastoma surgery fails. It's impossible to remove all of the tumor without destroying the brain that hosts it. Change the experiment by using dust instead of sand, and the full scope of the problem begins to show itself. Not only are cancerous residues everywhere, but they can't even be seen. It's a hopeless situation, at least with today's technology.

When Dr. Assistant Surgeon of my own surgical team told my wife that they had "got it all," she was overjoyed. Little did she or I know that there is no getting it all in glioblastoma. The tumor always grows back, typically sooner and only in rare cases later. And yet my surgery was considered a great success by the standards of modern medicine, having extracted more than all of the tumor visible by Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI). This was accomplished with the aid of a fluorescent dye, 5-aminolevulinic acid (Gliolan), that selectively stained tumor tissue, allowing even more of it to be removed than usual. The term for this kind of unusual procedure is "supermaximal resection." Dr. Staff surgeon put it this way in their report:

… I had achieved a gross total resection of the enhancing portions of the tumor as well as any fluorescent portions of the tumor.

The concept of "enhancement" is pivotal to understanding glioblastoma, brain MRIs, and disease progression. Unfortunately, I've never found a concise explanation for the term. I'll do my best to give one here.

Patients diagnosed with or suspected of having a brain tumor receive a special MRI procedure. In addition to normal series of scans, additional scans are performed after the injection of "contrast agent."

A contrast agent is a substance administered by intravenous (IV) injection at some time during an MRI study. In the old days, the study would be halted, then the patient would be removed from the machine and contrast agent would be injected by syringe. Modern facilities use an updated procedure in which the patient is fitted with an IV. Rather than interrupting the study to inject contrast agent, the injection is made through the IV catheter as scans are collected.

This special procedure yields two sets of scans: those acquired before the injection of contrast agent ("pre-contrast"); and those acquired after the injection of contrast agent ("post-contrast").

You might wonder what all this hassle buys. The short answer is information. Tumors vary in severity. The purpose of contrast agent is to pinpoint the most severe kinds of tumors.

Less severe tumors show up as T2-hyperintensity (or brightness) only. This kind of MRI feature suggests swelling. This is not good, but still better than what's seen in more severe tumors. There, swelling is compounded by damage to the brain itself. And that damage can be detected by comparing pre- and post-contrast MRI images. Regions that show brighter post-contrast indicate ongoing damage.

The human brain is protected from infection and poisoning by something called the "blood-brain barrier (BBB). Wikipedia describes the BBB this way:

The blood–brain barrier (BBB) is a highly selective semipermeable border of endothelial cells that regulates the transfer of solutes and chemicals between the circulatory system and the central nervous system, thus protecting the brain from harmful or unwanted substances in the blood.

Contrast agent injected into the bloodstream is normally invisible on brain MRI images because it's contained within blood vessels and therefore doesn't cross the BBB. For this reason, pre-contrast and post-contrast scans in cancer-free brains tend to look similar.

However, many kinds of brain damage disrupt the BBB. In essence, the BBB leaks. This leakage shows up as brightness in post-contrast images that's absent in pre-contrast images.

Last September I described progression, or tumor growth. For months leading up to this, Dr. Neuro-Oncologist had ascribed the bright spots ("T2-hyperintensity") on my MRI studies to treatment effects. The problem goes something like this. T2-hyperintensity indicates swelling. But swelling can be caused either by tumor growth or response to chemoradiotherapy. The latter optimistic interpretation turned out to be incorrect when the bright spots on my MRI studies persisted long after treatment effects were plausible.

But the regions of T2-hyperintensity in my MRI studies lacked something that the most aggressive tumors have: enhancement.

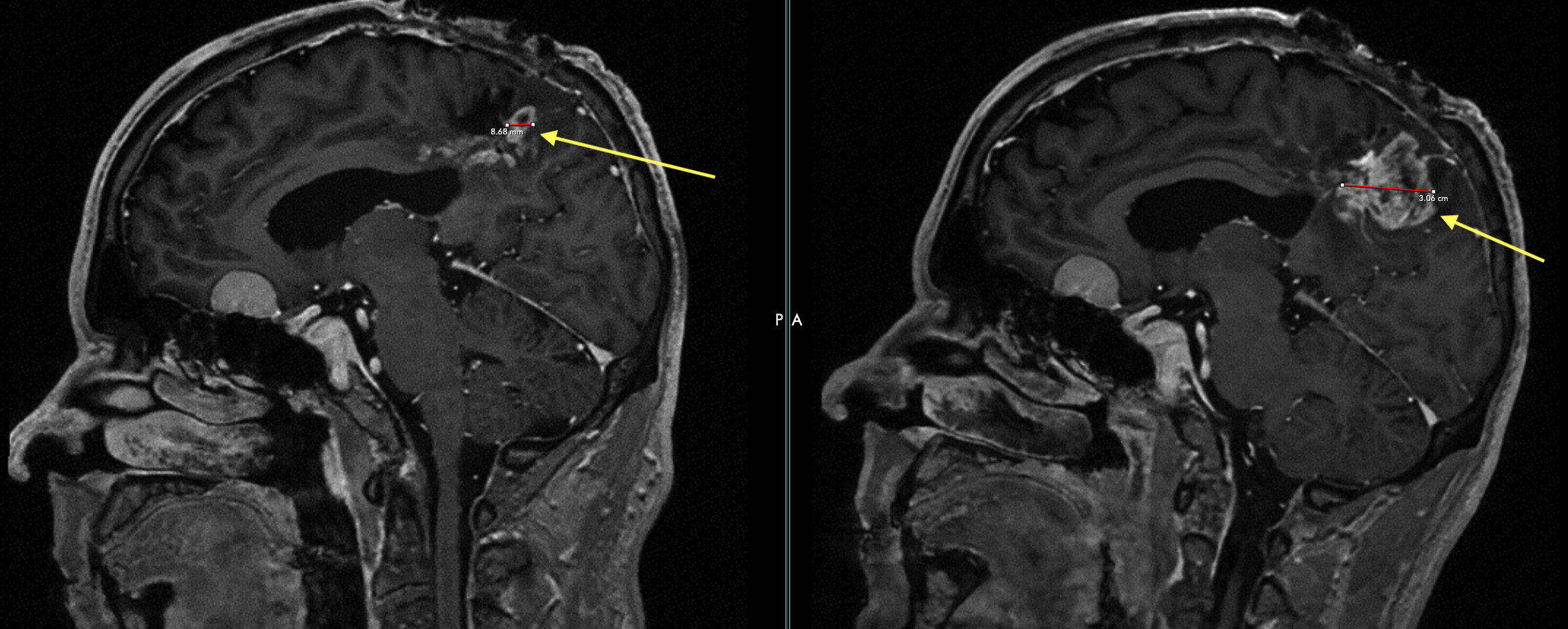

This changed on April 5, when the MRI collected on that day showed areas of enhancement. The radiologist impression summarized it this way:

Findings overall suggestive of progressive disease with interval increase in nodular enhancement along the right paramedian parietal lobe measuring 33 x 23 mm with associated hyper perfusion and associated interval increase in bulky T2/FLAIR hyperintensity within the right parietal region with greater confluence in the right periatrial [sic] white matter and right splenium of the corpus callosum …

The phrase "interval increase" signals that the current study is being compared to a previous one. Here, the basis for comparison was the study of February 2, 2024. In that earlier study the nodular enhancement consisted of two foci near each other measuring 15 and 12 mm, respectively. In other words, this regrown enhancing tumor had approximately doubled in size within the span of just two months.

Keep in mind that diameters change with the depth and angle of the slice being examined.

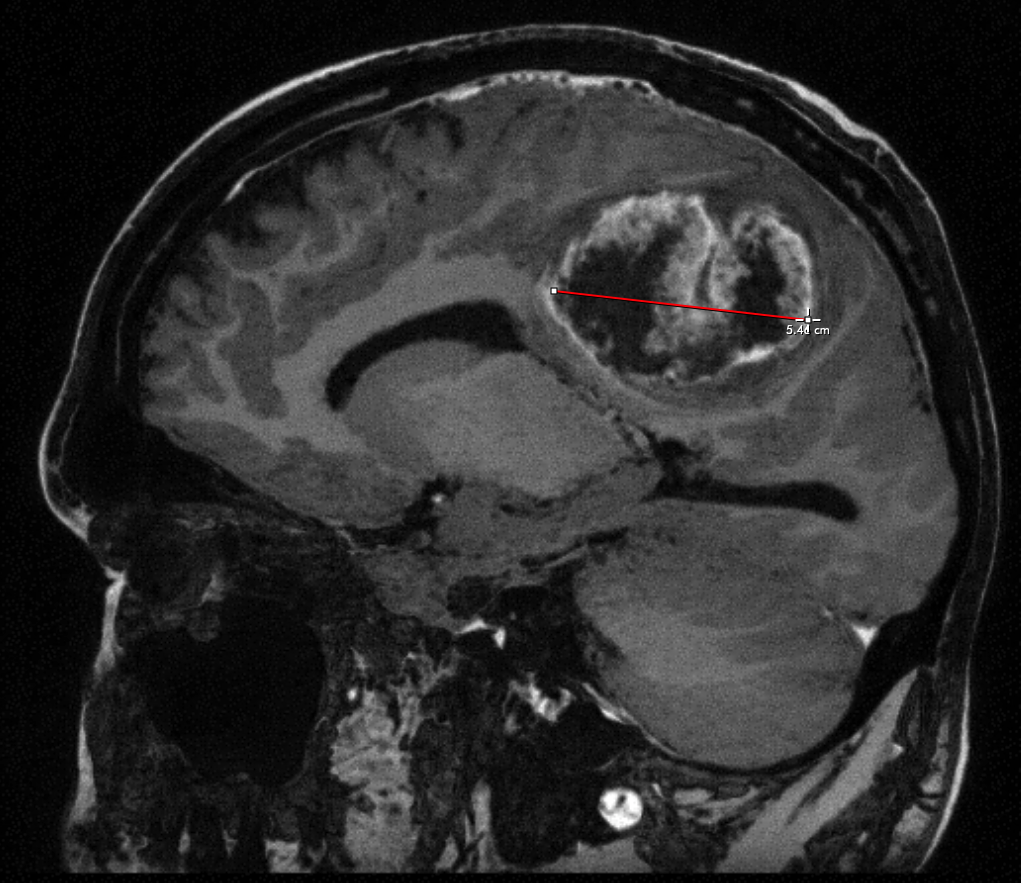

The location of this enhancing tumor lies within the same general area of the first — the right parietal lobe. On top of this, the size of the regrown tumor was found to be half of the size of the original tumor removed in March 2023 (3 cm vs 5.5 cm).

For comparison, an MRI of the original tumor with the same view (sagital) appears below.

The most misleading phrase a glioblastoma patient can hear is "got it all." There is no getting it all in the colloquial sense for glioblastoma surgery because the tumor isn't a lump. As a result, the tumor can grow back close to where the original was removed. This is not uncommon, and has happened in my case. Glioblastoma tumors grow quickly. My recent MRI studies suggest a doubling time of roughly two months.