CTfile Character Encoding

The CTfile family includes the widely-used serialization formats Molfile and SDfile. Users rarely need to consider the many details of these formats because they're handled by software. But data corruption can result when one utility misreads the output of another. The problem is especially hard to diagnose when the root cause lies close to the base layer. This article considers one especially vexing kind of data corruption that can occur across the entire CTfile family.

Source Documentation

Most of the information presented in this article is based on three documents published by CTfile's previous and current sponsors:

- CTFile Formats: BIOVIA Databases 2020 ("the specification"). This document describes CTfile syntax.

- Chemical Representation 2020 ("the guide"). This document describes CTfile semantics.

- Description of Several Chemical Structure File Formats Used by Computer Programs Developed at Molecular Design Limited ("the paper"). This is the first published description of the CTfile family of formats.

I refer to these documents collectively as "the documentation." The first iterations were published by Molecular Design, Limited, which later was renamed to MDL Information Systems. After a series of ownership changes, the documentation is now maintained by BIOVIA, a subsidiary of Dassault Systèmes.

Character Encoding

At the very bottom of the CTfile stack sits a character encoding. Wikipedia defines the term as follows.

Character encoding is the process of assigning numbers to graphical characters, especially the written characters of human language, allowing them to be stored, transmitted, and transformed using digital computers. The numerical values that make up a character encoding are known as "code points" and collectively comprise a "code space", a "code page", or a "character map".

As a technical aside, some language systems bidirectionally map a single character to a single code point. For example, the code point 65 is often mapped to the latin character "A". However, this is a special case. More generally, a character can be constructed from more than one code point. Latin scripts with diacritics (e.g., the German "ü") offer some examples, but there are many others. Fortunately, this detail can be ignored for the purposes of this article.

What can't be ignored are two key concepts about character encodings. First, the fundamental unit of character encoding is the code point. A code point is an integer index pointing to an entry in a code space. Second, a character encoding is what enables a byte sequence to be transformed into text, and vice versa.

And therein lies the catch. Transforming a byte sequence into a character sequence requires a character encoding. Without that, a reader has two choices: (1) refuse to process the sequence; or (2) guess the character encoding. If decades of computer science research had only ever produced a single character encoding, then guessing would work all of the time. Of course things turned out very differently. Numerous character encodings have been invented, many of them mutually incompatible with each other. So guessing may or may not work.

Therefore, the most important question to ask when receiving a byte sequence purporting to represent text is: "What's the character encoding?" In his widely-cited article on unicode, Joel Spolsky framed the issue this way:

Almost every stupid "my website looks like gibberish" or "she can’t read my emails when I use accents" problem comes down to one naive programmer who didn’t understand the simple fact that if you don’t tell me whether a particular string is encoded using UTF-8 or ASCII or ISO 8859-1 (Latin 1) or Windows 1252 (Western European), you simply cannot display it correctly or even figure out where it ends. There are over a hundred encodings and above code point 127, all bets are off.

Before we can even hope to turn a byte sequence into a string, let alone meaningful cheminformatics data structures, we need to know the character encoding.

What the Documentation Says

Despite its importance for error-free interpretation of CTfile content, the documentation says very little about character encoding. The paper and the early versions of the specification and guide say nothing at all. Later versions of the specification briefly mention character encoding, but only in the limited context of XDfile, an XML-based replacement for SDfile.

Either CTfile's maintainers aren't aware of the problems Spolsky and others have pointed out, or they don't want to do anything about it. Whatever the case may be, those attempting to implement error-free CTfile readers and writers have but one option: guess a character encoding.

Fortunately, we can simplify the problem drastically by noting two historical facts: (1) at the time that CTfile was created, there was only one widely-used format for the exchange of text between computer systems; and (2) today there is only one as well. CTfile was created before the character encoding dust was kicked up, and today that dust has settled. As a result, only two encodings need to be considered: ASCII and UTF-8.

ASCII

CTfile's inception in 1979 coincided with the dominance of the the American Standard Code for Information Interchange ("ASCII" and more formally "US-ASCII"). ASCII is a character encoding with a code space of 128 code points. These code points map to the Arabic numerals, upper and lower case English letters, printable symbols, and some control characters. Only seven bits are required. Systems based on 8-bit octets (most of them from the 1980s onward) leave the high order bit unset when encoding ASCII. This nuance will come into play shortly.

ASCII's rise to prominence was fueled by the leadership role played by the United States in theoretical and applied computer science. The US had "naming rights." ASCII contained most of the characters already present on US typewriters. The deal was sealed by president Lyndon Johnson's famous memorandum designating ASCII as the de facto standard for equipment bought by the Federal Government:

All computers and related equipment configurations brought into the Federal Government inventory on and after July 1, 1969, must have the capability to use the Standard Code for Information Interchange and the formats prescribed by the magnetic tape and paper tape standards when these media are used.

From 1970 onward, any computer hardware or software manufacturer hoping to sell to the US government needed to ensure that their products used ASCII encoding.

One other bit of context, drawn from the paper, is worth mentioning. The term "FORTRAN format" is used. FORTRAN format specifiers are character sequences that cause output from FORTRAN programs to be printed in well-defined and useful ways. FORTRAN 77 was the most widely-used version of the FORTRAN programming language at this time, and it encouraged the use of ASCII.

From this perspective, it's not surprising that the paper doesn't mention character encoding. Molecular Design Limited, the US-based company built around CTfile, would have been aware of Federal Government policy. It would have also known about the fragmented, often vendor-specific support for encodings other than ASCII. Had another encoding been used by CTfile, this would have been noteworthy enough to include in the paper. Character encoding was not mentioned because ASCII was the only practical option.

UTF-8

ASCII's limitations eventually led to the creation of UTF-8, a superset of ASCII that is used widely today. UTF-8 defines a code space of 1,112,064 code points, the first 128 of which are identical to the ASCII set. Whereas each code point in ASCII can be represented by a single 8-bit octet, the octet length for UTF-8 code points varies from one to four. This system was described very well in How does UTF-8 turn “😂” into “F09F9882”?. Incidentally, UTF-8 is not a contender for the character encoding used by CTfile, at least as of the 1992 paper. The reason is that UTF-8 would not not even conceived until several months later.

Is it possible that CTfile migrated at some point from ASCII to UTF-8, without mention in either the specification or guide? Answering that question requires a detour onto the topic of compatibility.

Compatibility

CTfile stands out among cheminformatics serialization formats for its creators' commitment to compatibility. In the context of encoding data, compatibility comes in two forms: forward compatibility and backward compatibility. An especially clear distinction between them comes courtesy of the W3C draft document [Editorial Draft] Extending and Versioning Languages: Terminology:

A language change is backwards compatible if consumers of the revised language can correctly process all instances of the unrevised language. Backwards compatibility means that a newer version of a consumer can be rolled out in a way that does not break existing producers. …

A language change is forwards compatible if consumers of the unrevised language can correctly process all instances of the revised language. Forwards compatibility means that a newer version of a producer can be deployed in a way that does not break existing consumers. …

In general, backwards compatibility means that existing texts can be used by updated consumers, and forwards compatibility means that newer texts can be used by existing consumers. … A backward compatible change to a language enables consumers of the updated language to be deployed without having to update producers. A forward compatible change to a language allows producers of the updated language to be deployed without having to update consumers, shown below …

We can use these definitions to explore the relationship between ASCII and UTF-8. Recall that UTF-8 is a superset of ASCII. Therefore, UTF-8 (revised language) is backward-compatible with ASCII (unrevised language) because every UTF-8 reader can correctly process the output of an ASCII writer. However, ASCII (unrevised language) is not forward compatible with UTF-8 (revised language) because ASCII readers cannot correctly process all instances of UTF-8.

Notice that backward compatibility does not imply forward compatibility. An ASCII consumer (unrevised language) will not correctly process all instances of UTF-8 (revised language). One of two things will happen when an ASCII reader encounters an octet whose high order bit is set: (1) an error will be generated; or (2) the high order bit will be dropped, leading to gibberish. Neither outcome would be consistent with correct processing.

CTfiles use ASCII Encoding

As noted previously, the documentation itself is silent on the topic of the character encoding used by CTfile. Fortunately, other sources speak to the issue.

The first is contained in a treatise on the major computer information systems as of 1990, Computer Graphics and Chemical Structures. Two-thirds of the book is dedicated to software published by MDL. This software includes REACCS, MACCS-II, and the Chemist's Personal Software Series (CPSS). All used CTfiles in one form or another for communication between MDL software, and with other systems. The Acknowledgement section notes:

In the first place, I thank the members of Molecular Design Limited, particularly: Dr. Guenter Grethe, Director, Scientific Applications, for his support during the preparation of this book; his cooperation made the author's task much easier; Guenter also critically reviewed the Parts describing the MDL systems, especially REACCS; many of his suggestions made the presentation better and more complete …

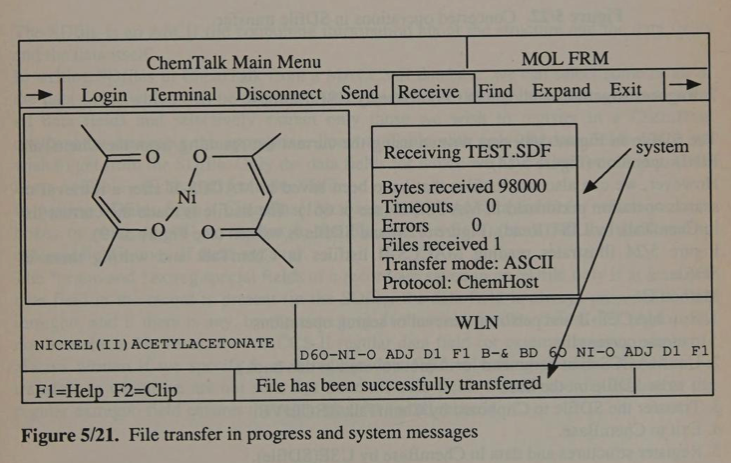

Part Five discusses ChemTalk, the system linking the CPSS suite running on IBM Personal Computers with MDL's software packages running on mainframes and minicomputers. CTfile was the format used to move chemical information among these systems

The first clue of a character encoding comes on page 763 (and on p 768), where a screenshot indicates that the transfer mode for receiving an SDfile was "ASCII."

The second clue is an explicit statement about the SDfile format (p 765): "The SDfile is an ASCII file containing information about the structure and the data fields and the data itself."

The second source comes by way of the Perkin-Elmer website. James Dill, one of the four-member team at MDL in 1978 recalled in an interview the following:

Our plan was to assemble an arsenal of computational chemistry programs into a system for designing molecules to order. We would take a customer's data, run it through our machine, and out would come potent drug candidatesÑthat [sic] was the plan. We began collecting programs and soon ran across the first problem to be solved: how to represent a molecule in some portable format which could be transferred between programs. A series of evening e-mails ensued, resulting in what Todd called the Standard Molecular Utility (SMUT) File, fortunately later renamed the Molfile before it became a world-wide standard.

We agonized over whether the smutfile [Molfile] should be readable ASCII or compact binary, and opted for the former even though it consumed precious disk space. So how do we represent molecules today? [my emphasis] …..

Perhaps these references to "ASCII" in two different sources really refer to one of the many "extended" ASCIIs in use at the time. But I very much doubt it. None of them could be relied upon to work across not just on mainframes and minicomputers, but also the IBM personal computer on which CPSS ran. The only character encoding capable of doing that was ASCII, not some proprietary or niche extended version of it. Even so, basing CTfile on such an out-of-the-way encoding would again put the onus of explicitly naming it on MDL, which as we have seen it has not done — repeatedly.

UTF-8 and CTfile

We're now in a position to consider what happens when an older ASCII-only CTfile reader encounters the output of a hypothetical modern CTfile writer using UTF-8. On encountering an octet whose high order bit is set, an older reader will respond by either reporting an error or misinterpreting the octet as an ASCII character. Given that UTF-8 is a variable-length character encoding, a single emoji can translate into four or even more characters of ASCII garbage. The line length constraints imposed by some of CTfile's member formats can interact here in vexing ways.

In other words, if a CTfile were to use UTF-8 encoding, the result would be either to break ASCII-only CTfile readers or cause them to corrupt certain files. Given that CTfile's creators have left us no choice but to speculate about character encoding, it's reasonable to ask how they would view the incapacitation of older readers by UTF-8.

A Commitment to Compatibility

Although the CTfile family has undergone changes over the years, these have occurred under a strong commitment to compatibility. The authors of the paper left no room to misinterpret their intent or the forces driving their decision making:

The evolution of the CTfile formats did not proceed by a well-defined plan. Changes were frequently made over the years to accommodate new program features or application needs. While the changes often added new data fields or appendices, they were done such that older files would remain valid and older programs could read the portion of new files they could interpret. Because of this policy, as well as the widespread use of programs which read and write CTfiles, there is probably more valid chemical structure information in existence in these formats than in any other format, current or proposed.

With respect to the hypothetical use of UTF-8, the most important phrase is: "older programs could read the portions of new files they could interpret." The authors are describing forward compatibility. Old CTfile readers were capable of processing all instances of new CTfile versions, ignoring what they didn't understand.

CTfile achieved this outcome in part by instructing readers to ignore those parts of a file they don't understand. A good example comes in the part of the specification dealing with the V2000 molfile properties block, which states that "[a]ll lines that are not understood by the program are ignored" (p 47).This selective disregard, combined with a common header format, allows V2000 molfile readers to process V3000 molfiles without entering an error state. The same approach has been taken within V3000 molfiles, which enable various kinds of extensions.

CTfile has at times failed to make good on this commitment. An older example would be restrictions added to the characters allowed in an SDfile data header. A recent example would be removal of some default valence states for atoms in molfiles. Nevertheless, these examples represent exceptions rather than the rule. Moreover, when changes like this happen, they are documented.

It's tempting to dismiss the value of keeping "older programs" working. Before doing so, however, consider the large body of cheminformatics and computational chemistry software written long ago but still in use today. Some packages were not based on general purpose toolkits that would have been updated over the years, but rather custom implementations of CTfile readers and writers. Some of those were not written using standard libraries having access to newer character encodings such as UTF-8.

Implications of ASCII-Only CTfiles

Restricting CTfiles to ASCII-only code points brings with it some harsh consequences. Molfile offers two main opportunities for freeform text: the molecule name and comments field. In this sense, the unavailability of higher code points presents some loss in functionality. The more difficult case is SDfile, which pairs a molfile with freeform data. Here a wide range of more commonly used non-ASCII code points are likely to be found: the degree symbol; currency symbols; greek letters in systematic names; various languages including those based on non-latin alphabets; and of course emojis. Restricting the entire CTfile stack to ASCII means rejecting such data and more.

It's tempting to seek middle ground when faced with such a choice. Perhaps SDfile could be interpreted as an ASCII-based binary format with text-based data fields. The main problem is defining the boundaries and within each zone. As noted in the W3C XML specification, inline definition of character encodings is in the general case a "hopeless situation.". Unlike XML, CTfile offers no method whatsoever to signal character encoding.

Fortunately, those wanting to use UTF-8 encoding within the CTfile family do have an option: XDfile. This XML-based format supports UTF-8 encoding. As a bonus, XDfile offers a much more flexible model for structure-data association than SDfile.

CTfile isn't the only format to find itself in a world whose character encoding rules have shifted drastically. Take the Comma Separated Values CSV format for example. First introduced in 1972 and still widely-used today, CSV defined no character encoding. The question of whether to standardize CSV or get rid of it altogether continues to generate debate. And some of that debate hinges on UTF-8.

Other Discussions

The only other detailed discussion about character encoding and the CTfile format that I'm aware of is this Twitter thread, from which some ideas have been drawn for this article.

Conclusion

Modern implementations of CTfile readers and writers face a choice: use the most likely original character encoding of CTFile (ASCII), or adopt today's most commonly used character encoding (UTF-8). Those choosing the latter path should at least be aware of their likely abandonment of an important, explicit, decades-old commitment to compatibility.