Penny Codes

A fingerprint is a molecular representation that omits certain kinds of structural information with the goal of increasing computational speed. The success of this approach is evidenced by numerous modern applications ranging from structure search to property prediction. A good fingerprint trades just enough structural information to achieve the desired computational goal, so flexibility matters. Given the versatility and power of fingerprints, it's not surprising to find a continuous line of research extending back more than five decades. What is surprising, however, is how much of the early research has been forgotten — and perhaps prematurely so. This article presents a case in point.

Penny Codes in a Nutshell

A Penny code, first described by Robert Penny in 1965, represents the extended connectivity environment around an individual atom within a molecular graph. All of the atoms located within a three-atom radius of perception contribute to the code, but in different ways. A molecular Penny code is the set of all atomic Penny codes for a given molecular graph.

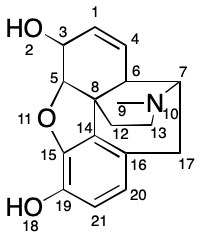

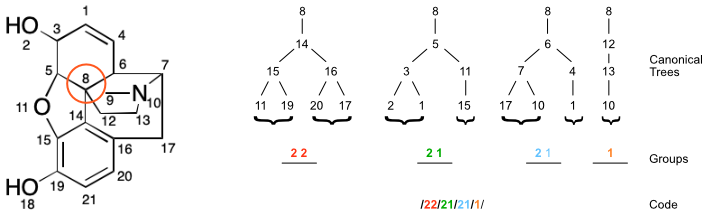

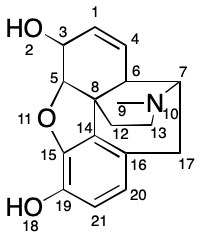

Penny's paper uses a running example of the morphine molecule.

Consider atom 8, a quaternary carbon. The procedure described by Penny yields the following canonical string-based code:

/22/21/21/1/

What follows is a procedure for generating Penny codes and a few variations on the idea.

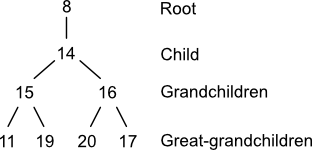

Planted Trees

Penny codes take as their starting point the graph theoretical construct of the planted tree. A planted tree is a tree whose root node has degree one. The planted trees used to compute Penny codes are comprised of up to four generations: one parent (root), one child, zero or more grandchildren, and zero or more great-grandchildren.

A planted tree can be constructed from a molecular graph and an atom using a directed depth-first traversal. First, select an arbitrary node and record it as the tree's root. Then select an arbitrary child and record it. Freely traverse and record the remainder of the graph's nodes starting at the child and terminating if a path of four nodes is obtained. When describing planted trees, it's sometimes convenient to use the term "child" in the relative sense. For example, node (15) in the planted tree above has two children.

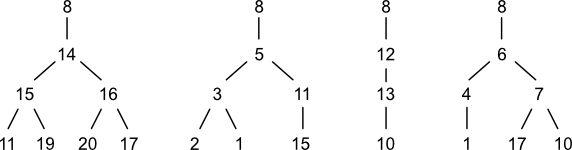

Four planted trees are associated with node (8) in morphine. Notice that three atoms are repeated across this set at the grandchild level: 1; 10; and 17. Other repeated nodes span the grandchild-great grandchild levels: 11 and 15. This repetition indicates the presences of cycles. Penny describes some ways to use this information. However, with one exception, cycles don't play a role in generating codes. That exception is cycles of size three such as cyclopropane. Penny doesn't mention how to handle case, but there are a few options. One would be to disregard the cycle-closure node. Another would be to include it. Still another would be to create a special notation for it.

Anatomy of a Code

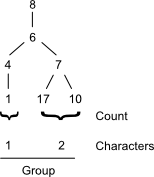

A Penny code is composed of zero or more groups. A group is a data structure summarizing the connectivity of one planted tree. The number of groups within the code for a given atom equals its degree (neighbor count).

A group is in turn composed of zero or more characters. A character is a non-negative integer value representing the child count for each grandchild in a planted tree. If a rooted tree has no grandchildren, then the corresponding group is empty.

In the previous section, four planted trees were identified for node (8). These trees are represented by the following four groups, respectively: [2 2]; [2 1]; [1]; and [1 2].

Computing a Code

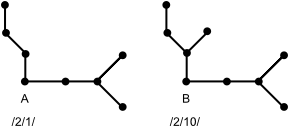

The rooted trees at a given atom are compiled into groups, which collectively make up the atom's code. Penny's paper uses a string-based representation beginning with a forward slash character ('/'). Each group is then encoded as a string by concatenating its characters and appending a forward slash character. The result is then appended to the code. For example, a planted tree yielding the characters [2, 3] would yield a group string of 23/. An empty group would be represented by just a forward slash: /.

In this manner, the code for node (8) in morphine becomes:

/21/12/1/22/

Canonical Codes

The method for generating codes isn't very useful at this point because child nodes are selected arbitrarily. This leads to arbitrary ordering of trees and branches within each tree. Ultimately, this yields different codes depending on the order of depth-first traversal.

What's needed is a way to build codes that's independent of the order of child selection. One approach would be to canonicalize the set of planted trees. This could be accomplished as follows:

- Sort trees by descending degree (neighbor count) of each child.

- Sort grandchildren within each tree by descending degree.

The ordering of trees and branches can take place either during or after depth-first traversal. To canonicalize trees on the fly, place additional constraints on the traversal. In particular, select the branch of highest degree.

Given a set of canonicalized planted trees, the same atomic codes will always be generated. Returning to node (8) in the morphine example, the canonicalized code would be:

/22/21/21/1/

The overall procedure for generating a code from a molecular graph is depicted in the figure below.

Molecular Code

Generating a canonical code for each atom in a molecule yields a molecular code. The following collection of atomic codes is obtained for morphine.

| Atom(s) | Code |

|---|---|

| (1, 21) | /20/2/ |

| (2, 9, 18) | /21/ |

| (3) | /31/1// |

| (4) | /32/2/ |

| (5) | /221/2/10/ |

| (6) | /211/21/1/ |

| (7) | /31/2/10/ |

| (8) | /22/21/21/1/ |

| (10, 19) | /21/1// |

| (11) | /32/22/ |

| (12) | /222/2/ |

| (13) | /3/20/ |

| (14) | /221/221/11/ |

| (15) | /32/2/10/ |

| (16) | /32/2/1/ |

| (17) | /22/21/ |

| (20) | /21/2/ |

A useful property of a molecular code is its ability to partition the atoms of the corresponding molecular graph. The molecular code for morphine creates 17 partitions, all of which except three are singly-occupied. Notice that some of the multi-occupancy partitions can be further split by considering atomic number. This atomic partitioning is itself useful in canonicalization and other applications.

A molecular Penny code fulfils one of the requirements for a fingerprint by omitting certain kinds of structural information. The next sections will show some ways in which this data reduction can be traded for computational performance.

Exact Structure Screening

The application of molecular codes to exact structure screening is straightforward. Given query and target graphs, generate the molecular codes for each. If the codes match in terms of both identity and count, the target graph passes the screen and a full search can proceed. Otherwise the query can't possibly match the target and so atom-by-atom search can be avoided.

This type of screening is unlikely to be used in practice given the availability of canonical identifiers such as InChI.

Substructure Screening

In analogy to exact structure screening, Penny codes can also be used for substructure screening. In this case, however, rather than equality of codes, the goal is to find congruity.

A code C is said to be congruent to another code C' if each group in C can be uniquely matched with a congruent group in C'. A group G is said to be congruent to another group G' if each character in G can be uniquely match with a congruent group in G'. Finally, a character X is said to be congruent to another character X' if it is less than or equal to X'.

Optimizing Atom-by-Atom Search

Fingerprints used to accelerate substructure search today are only used for screening, not the subsequent confirmation step. Penny codes, in contrast, can be used for both. This unique capability could make the invention from 1965 a useful subject of further research today.

Several algorithms for substructure search have been described. The most popular of these are atom-by-atom searches. Exemplified by Ullmann's algorithm, they proceed through iterative attempts to pair a node in a query graph with a node in a target graph. If the two nodes are compatible, then an attempt is made to pair the corresponding neighbors within each graph, and so on.

The main source of inefficiency in atom-by-atom searches is backtracking. If at any point two incompatible nodes are paired and no other candidates are available, the algorithm must return to the last compatible branch point and find another candidate pairing. If none are available, then further backtracking is performed. And so on until another search branch can be started. In the worst case, the entire set of pairings will need to be redone n times, where n is the number of nodes.

By incorporating medium-range connectivity information, atomic Penny codes can be used to signal incompatibility before backtracking takes place. As a precondition the search algorithm would compare a candidate pair for congruency. If the source code is not congruent with the target code, the pairing must be incompatible and so can be rejected. In this way, atomic Penny codes can augment known backtracking avoidance techniques.

Extensions

The code described in Penny's paper focuses exclusively on connectivity. This gives the base code great flexibility to carry additional information useful within specific applications. For example, the base code says nothing about atomic identity. A straightforward set of modifications would add information such as atomic number, isotopic composition and charge. Similarly, the base code says nothing about bonding. Even greater discriminatory power could be achieved by including the degree of unsaturation (number of double bonds) or other bonding invariants.

The utility of such extensions will in large part depend on their overall costs. Each bit of new structural information adds to the time and space complexity of code generation. Perhaps more significantly, additional resources will also be required to determine congruence. At some point the added costs of generating and testing codes for congruence could outweigh the performance gains from using the codes.

Using Codes

The state-of-the-art for substructure screens is the path-based fingerprint. In a nutshell, the set of all paths up to a given length is collected for a group of target molecules. The same set of paths is generated for a query molecule. If all of the paths in the query are present in the target, an atom-by-atom search is performed. Otherwise, the target is rejected.

The problem with this approach is that the number of paths through a molecule grows rapidly with the number of atoms. This can lead to an unmanageable number of paths when multiplied over a molecular collection. This problem is solved through additional data reduction. The paths of a molecule are encoded as strings and added to a Bloom filter. The resulting bit vector is then used as part of a high-performance screening algorithm. Bloom filters didn't appear for several years after Penny's paper, but a bit of retrospective "bit juggling" can get the two working together.

This Bloom filter approach could be applied to Penny codes, provided that it accounted for congruence. Each atomic code contains information not just about the atom itself, but its immediate environment up to three atoms away. But the nature of substructure search means that this environment may or may not be relevant. Simply adding atomic codes to a Bloom filter would result in a screen that would unacceptably produce false negative results.

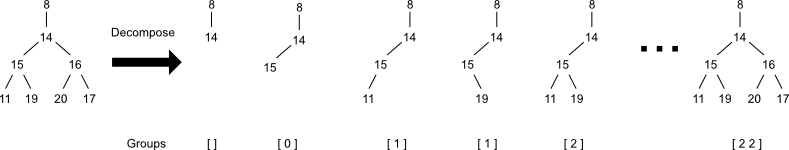

One solution to the congruence requirement is decomposition. Decomposition transforms a single atomic code into a set of codes representing the loss of all possible combinations of descendants. This set of codes could be generated from the corresponding set of rooted trees. These trees could in turn be generated by collecting not just the final trees, but all intermediate stages as well. Notice that the simplicity of atomic codes (and their underlying group data structure) means that decomposition could be accomplished directly on them, without the need to enumerate the underlying trees.

Decomposing each atomic code would yield a superset of the original molecular code. Adding all of these atomic codes to a Bloom filter would produce a bit vector that would serve as a drop-in replacement for path-based fingerprints.

Other applications such as quantitative structure-property relationship prediction and machine learning wouldn't require decomposition at all. The set of (possibly extended) Penny codes could be added directly to the Bloom filter to generate the necessary bit vectors.

These are just a few simple ideas. Given the wide range of applications for fingerprints devised over the last few decades, there are no doubt many other ways to adapt Penny codes to modern technology stacks.

Circular Fingerprints, Morgan's Algorithm, and Others

If you've spent any time using circular fingerprints (AKA Extended Connectivity Fingerprints, or ECFPs), Penny codes should look familiar. The underlying idea is strikingly similar: encode information about the surrounding environment of each atom out to a maximum radius of perception. In this sense, ECFPs could be viewed as a specialized form of Penny code.

Nevertheless, this close connection appears to have escaped the authors of the paper describing ECFPs. Penny's paper does not appear once in the ECFP paper's 107 references. Moreover, only 27 papers ever cited Penny according to Google Scholar. Most of these citations appear before 1980, after which interest in Penny codes dropped off rather quickly. The early papers that do cite Penny are quite interesting in their own right, and may be the topic of future posts. For that matter, Penny himself cites a few works and applications that could be of interest today.

Compared to ECFPs, Penny codes are much easier to compute because they are so much simpler. This simplicity could pay off in certain situations. For example, ECFPs are not used for substructure screens, presumably due to the time and space complexity of decomposition. Perhaps there are other applications in which ECFPs are overkill and Penny codes would perform better.

The ECFP authors do cite Morgan's algorithm. It is in fact mentioned multiple times in the text, a relationship that explains why ECFPs are sometimes referred to as "Morgan fingerprints." This is surprising given that Morgan's algorithm only tangentially deals with the problem of obtaining extended connectivity codes, which Morgan called "connectivity values." Most of Morgan's discussion centers on the numerous other considerations involved with molecular graph canonicalization.

The notion of fingerprints based on extended connectivity is not unique to ECFP. The idea crops up in both the DARC system and the Signature descriptor. The former introduced the idea of "fragment reduced to an environment that is limited" (FRELs). The latter was "based on extended valence sequence." Neither original paper mentions Penny, nor to my knowledge do any of the published sequels. A more recent example can be found in work that introduces the concept of "molecular shingling," which can be thought of as a modified Penny code although Penny is not mentioned there, either.

Oddly enough, Penny's paper immediately follows Morgan's paper in the same issue of the Journal of Chemical Documentation (which ultimately became the Journal of Chemical Information and Modeling). As a result, Morgan himself never cites Penny, nor does Penny cite Morgan. This bibliographical accident may partially explain why Penny's work is so obscure. Morgan worked for Chemical Abstracts Service, even then a big player in chemical documentation. Penny worked for General Electric's Falls Church Virginia facility. As far as I can tell the paper discussed here is Penny's only contribution to the scientific literature.

Acknowledgement

I discovered Penny codes through Andrew Dalke, who gave an historical perspective on cheminformatics in 2020 (below). This presentation puts Penny codes into the context of work being performed before and after 1965. In 2021 Andrew mentioned Penny codes in the context of Morgan fingerprints.

Conclusion

A Penny code is a simple, flexible molecular fingerprint based on extended atomic connectivity. Largely forgotten since its first description in 1965, Penny's system can be viewed as the logical precursor to not only circular fingerprints but many other kinds of extended connectivity codes. The algorithm Penny presents is clearly described in detail, and adaptable to modern methods of fingerprint generation and use. At the very least Penny's simple yet functional system should be considered for inclusion in curricula and other documentation discussing fingerprints in cheminformatics.