The Trouble with Hückel

As the joke goes, the difference between computational chemistry and cheminformatics is that in computational chemistry molecules get to keep their hydrogens. The two fields clearly start from different assumptions, using them to answer different kinds of questions. One of the more striking differences between the two fields is the treatment of aromaticity. Today's article highlights the problems that can result when concepts are carelessly transplanted from one field to the other. A way forward is also proposed.

In a Nutshell

SMILES supports an atomic property, which I'll refer to as aromatic, defined in terms of "Hückel's rule." This rule, the result of applying simplifying assumptions to quantum mechanics, has a long history in chemistry. Unfortunately, Hückel's rule was never formulated in a way that is both detailed enough to reduce to software and general enough to cover all of organic chemistry. The result has been widespread disagreement over a foundational piece of cheminformatics infrastructure.

Hückel's Rule

Certain molecules containing alternating circuits of single and double bonds display much higher chemical stability than others. How can this phenomenon be understood, or at least predicted? The most widely-used tool is Hückel's rule.

Despite its widespread use in undergraduate courses and research, a concise yet complete description of Hückel's rule is not easy to find. The original work by Erich Hückel in the 1930s is verbose and written in German. Later formulations cited "4n+2" as the rule without enumerating the exact set of conditions that must apply. And as we'll see, the details matter.

The clearest and most complete expression of Hückel's rule can be found in the IUPAC Glossary of terms used in physical organic chemistry. Under the heading "Hückel's (4n + 2) rule, we find:

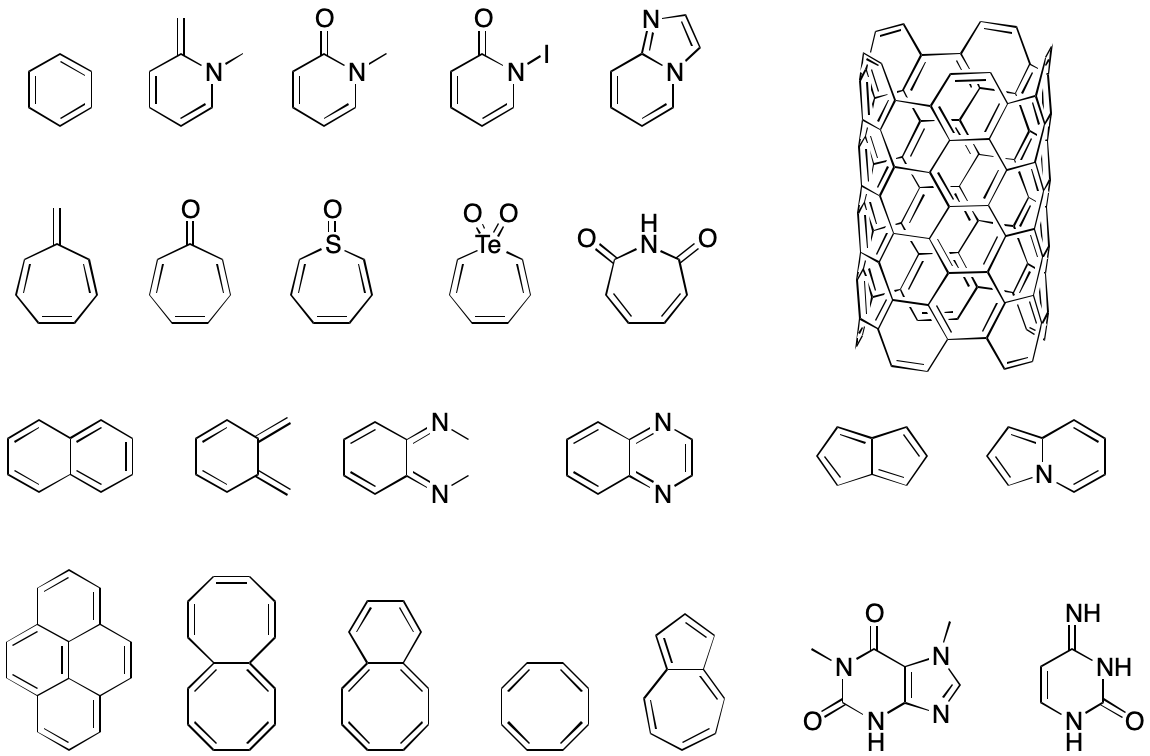

Monocyclic planar (or almost planar) systems of trigonally (or sometimes digonally) hybridized atoms that contain (4n + 2) π-electrons (where n is a non-negative integer) will exhibit aromatic character. The rule is generally limited to n = 0-5. This rule is derived from the Huckel MO calculation on planar monocyclic conjugated hydrocarbons (CHm, where m is an integer equal to or greater than 3 according to which (4n+2) π-electrons are contained in a closed-shell system. Examples of systems that obey the Hückel rule include:

Systems containing 4n π-electrons (such as cyclobutadiene and the cyclopentadienyl cation) are "antiaromatic".

Breaking this down, Hückel's rule applies to a molecular subgraph for which all of the following conditions hold:

- The subgraph is a singular cycle. This requires all bonding pairs of atoms to be known.

- The subgraph is planar. This requires the 3D coordinates of each atom.

- All atoms are "trigonally" or "digonally" hybridized. This requires a model for orbital hybridization.

- The π-electron count for the atoms in the cycle is typically equal to: 2; 6, 10; 14; 18; or 22. This requires a method for assigning atomic π-electron contributions.

The most widely-disregarded aspect of Hückel's rule is that it applies to single cycles only. Even naphthalenes, ubiquitous motifs in research and commerce, are disqualified. In 1952, Streitwieser and coworkers showed that independently calculated delocalization energies were inconsistent with the application of Hückel's rule over fused cycles.

Even a casual reading of the IUPAC formulation reveals that Hückel's rule assumes some information that won't always be available in the context of using SMILES. For example, SMILES by definition lacks atomic coordinates so determining planarity in the general sense will be impossible. Similarly, models of hybridization are likely to be primitive at best when using SMILES. But perhaps the biggest problem with the IUPAC definition is what it doesn't say.

The Quiet Parts

The IUPAC formulation of Hückel's rule leaves some very important points as exercises for the reader. Consider these questions:

- Can a cycle be "peeled" away from another cycle to reveal a singular cycle, as we might want to do in naphthalene?

- If so, how are electrons to be divided up?

- What is the π-electron contribution of an atom with an exocyclic double bond such as cyclopentadienone? How does this contribution change with electronegativity?

- What are the rules for determining π-electron contributions for singly-bonded heteroatoms? Can two such atoms be adjacent to each other in the cycle?

- What's the maximum allowable deviation from planarity?

Answering these questions consistently is no easy task. Each new corner case is sure to resurface the decades-old conflict between viewing aromaticity as a structural vs. behavioral phenomenon. The result would almost certainly be a patchwork of possibly contradictory rules that would provide a safe haven for the nastiest bugs. No two organizations faced with this problem would develop quite the same solutions, and even within an organization conflicts would be unavoidable.

SMILES and Hückel's Rule

SMILES supports an atomic boolean flag with the label aromatic. Setting this flag adds the atom to a construct I call the "delocalization subgraph." This construct and its uses were previously described. In a nutshell, the delocalization subgraph is a possibly empty, induced subgraph representing a delocalized electron system.

What value does the aromatic flag add? According to Dave Weininger, the creator of SMILES, the idea was to aid canonicalization. In the SMILES introductory paper he explains:

The SMILES language was specifically designed to be “canonicalizable”, i.e. not only to provide an unambiguous chemical nomenclature but also be able to express a single, unique SMILES for every structure in the same language. This implies a fundamental requirement to express the symmetry of a molecule correctly. Consider the problem of generating a unique SMILES for OclccccclF ortho-fluorophenol, but without aromatic bonds. There are two ways to write it, OCl=CC=CC=ClF (with the substituted carbons joined by a single bond) and OCl=C(F)C=CC=Cl (with the substituted carbons joined by a double bond). These are two different molecular graphs: the SMILES for these will always differ. For purposes of unique nomenclature, it is not acceptable to have two different “unique SMILES” for the same molecule. SMILES language provides an “aromatic” concept to avoid this conundrum.

Given its poor suitability to the task at hand, Hückel's rule was a surprising concept on which to base the SMILES aromaticity features. Nevertheless, the two are linked both in the primary literature and in software documentation. As noted by Weininger later in the introductory paper:

SMILES algorithms detect accurately the vast majority of aromatic compounds and ions. The system will accept either aromatic or nonaromatic input specifications; it will detect aromaticity and will convert the input structure accordingly. This is accomplished with an extended version of rule to identify aromatic molecules and ions.[reference an undergraduate organic chemistry textbook] To qualify as aromatic, all atoms in the ring must be sp2 hybridized and the number of available “excess” π electrons must satisfy Hückel’s 4N+2 criterion.[my emphasis] As an example, benzene is written clcccccl, but an entry of Cl=CC=CC=Cl (cyclo- hexatriene) - the Kekulé form - leads to detection of aromaticity and results in an internal structural conversion to aromatic representation. Entries of clcccl and clcccccccl will produce the correct antiaromatic structures for cyclobutadiene and cyclooctatetraene, Cl=CC=Cl and C1= CC=CC=CC=Cl, respectively. In such cases the SMILES system looks for a structure that preserves the implied sp2 hybridization, the implied hydrogen count, and the specified formal charge if any. Some inputs, however, may be not only formally incorrect but also nonsensical such as clccccl. Here clccccl is not the same as Cl=CCC=Cl (which is a valid SMILES for cyclopentadiene) since one of the carbon atoms is sp3 with two attached hydrogens. In such a structure, alternating single- and double-bond assignments cannot be made. The SMILES system will flag this as an “impossible” input.

There's a lot to parse here (including incompatible statements about aromaticity and antiaromaticity), but the bolded part is the most important. Setting the aromatic flag is a promise by the writer that the atom is part of a cycle that obeys Hückel's rule.

Ten years later, Weininger reiterated the same association between Hückel's rule and the aromatic flag:

How does SMILES determine “aromaticity ”?

Unfortunately it is not as trivial as “alternating single and double bonds”, but it is not rocket science, either. The SMILES algorithm uses an extended version of Hueckel’s rule to identify aromatic molecules and ions. To qualify as aromatic all atoms in a ring must be sp2 hybridized and the number of available “shared" π electrons must satisfy Hückel’s 4 N +2 criterion.

Similar statements can be found in the Daylight documentation.

OpenSMILES was an effort to resolve some of the ambiguities in the SMILES primary literature and documentation. Unfortunately, it adopted the same approach to the aromatic flag as its predecessors:

In an aromatic system, all of the aromatic atoms must be sp2 hybridized, and the number of π electrons must meet Huckel’s 4n+2 criterion When parsing a SMILES, a parser must note the aromatic designation of each atom on input, then when the parsing is complete, the SMILES software must verify that electrons can be assigned without violating the valence rules, consistent with the sp2 markings, the specified or implied hydrogens, external bonds, and charges on the atoms.

SMILES+ is an IUPAC initiative to formally specify SMILES. In more than two years of development, it has not changed the language around the aromatic flag used in OpenSMILES and inherited from the primary literature.

Despite multiple citations and ample opportunity to clarify, no source address the underlying problem of how to fill in the substantial blanks in applying Hückel's rule as applied to SMILES.

Moving Forward

Having built an essential SMILES feature on the shaky ground of Hückel's rule, three paths forward are now open: (1) do nothing; (2) refine Hückel's rule; or (3) replace Hückel's rule with something better.

Doing nothing is always an option. The current status quo has persisted for decades and may continue to work for several more. However, leaving this issue open will undermine any attempts to standardize SMILES, just as it did with OpenSMILES.

Alternatively, we can think of ways to adapt Hückel's rule. For example, Platt introduced a "perimeter rule" as a way to deal with fused benzenoid systems:

We define this group of hydrocarbons as follows. Every planar conjugated system has certain carbon atoms at the edge of the system which we may call "perimeter carbons." In a cata-condensed system or in a polyene, every carbon is on the perimeter (Fig. 6, hexatriene, anthracene). In a pericondensed system such as pyrene, there are additional carbons inside. If the perimeter carbons were removed, some or all of these additional carbons would lie on the new perimeter. These we may call "second-perimeter carbons." If the system is large enough, we may remove these carbons also, and have "third-perimeter carbons" within, and so on.

As noted by Randić, however, counterexamples to this approach are not hard to find.

Mostly forgotten by organic chemistry and cheminformatics, Clar's Sextet Rule offers another approach. As noted by Solà in a 2013 review:

Clar's rule states that the Kekulé resonance structure with the largest number of disjoint aromatic π-sextets, i.e., benzene-like moieties, is the most important for characterization of properties of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs). Aromatic π-sextets are defined as six π-electrons localized in a single benzene-like ring separated from adjacent rings by formal CC single bonds.

Unfortunately Clar's Rule creates a situation not unlike the one arising from a Smallest Set of Smallest Rings: non-uniqueness. Multiple Clar structures are possible for some molecules.

In their current form, Clar's sextet and Platt's perimeter may alleviate some friction between SMILES and Hückel's rule, but the issues of electron counting, geometry, and hybridization remain.

Replacing Hückel's Rule

An alternative to tweaking Hückel's rule is to replace it altogether. Cutting the cord has the advantage of specificity. Rules for setting the aromatic flag could reflect the needs of SMILES itself, rather than those of other applications as is currently the case.

The first step is to recall the original purpose of the aromatic flag: to enable canonicalization. Unless a bonding arrangement interferes with canonicalization, there's little reason for automated writers to set the aromatic flag at all. And as noted previously, setting the aromatic flag isn't even necessary for canonicalization. Pure valence bond representations can be canonicalized using similar procedures to those used when setting the aromatic flag.

Nevertheless, some writers will insist on setting the aromatic flag. The question then becomes, what specific guidance for doing so will ensure that the resulting string can be faithfully interpreted by all SMILES readers?

This is where the delocalization subgraph can come in. Think of it as a way to encode a perfect matching, without specifying one in particular. As explained previously, a perfect matching is a subgraph in which every node has degree one. Chemists will immediately recognize the connection to electron delocalization in the sense that the edges of a perfect matching over a delocalization subgraph become double bonds. Moreover, this process is reversible.

This just leaves the problem of constructing a delocalization subgraph from a valence bond graph. Only cyclic subgraphs cause the kind of electron delocalization relevant to SMILES canonicalization. So a reasonable starting point would be to start with the set of all cycles.

The only cycles of interest would be those consisting entirely of alternating single and double bonds. It turns out that this concept maps directly to the conjugated circuit. As explained in Milan Randić's landmark 2003 review on the topic:

Conjugated circuits are those circuits within an individual Kekule ́ valence structure in which there is a regular alternation of CC double and CC single bonds.

Conjugated circuits have been the topic of much theoretical study. For the purposes of SMILES, however, the definition alone suffices. Gone are the useless (and almost universally ignored) constraints around 3D coordinates, hybridization models, singular cycles, and electron counting imposed by Hückel's rule. In its place is a procedure requiring just two pieces of of information already carried by all molecular graphs:

- The set of all cycles.

- A method to identify single/double bond alternation.

An algorithm for setting the aromatic flag given a Kekulé valence bond graph could be developed as follows. For each cycle in the set of all cycles, check for single/double bond alternation. If found, add all atoms of the cycle to the delocalization subgraph. "Alternation" can be grounded mathematically through the concept of symmetric difference, which coincidentally pops up in the context of cycle basis.

Chemical Meaning

Why does any of this matter? Clearly there's enough consensus around how to apply Hückel's rule in SMILES to have gotten us this far. Why not let things be?

As mentioned previously, standardization is one reason. Aromaticity was perhaps the single most-discussed topic in the OpenSMILES effort. Ultimately, the problems caused by linking the aromatic flag to Hückel's rule could not be resolved. Any future attempts at standardization are likely to meet a similar fate until a better-suited model for the aromatic flag can be found.

A secondary problem is how SMILES are being used in practice. Consider this admittedly small survey I recently ran on Twitter:

I use aromatic SMILES mainly to:

— Rich Apodaca (@rapodaca) June 29, 2021

The third option in my survey was meant to ask if the aromatic flag was specifically being used to convey information not available through the Kekulé valence bond graph. Half of respondent's said "yes." Yet as we've seen, such a use directly contradicts both the letter and spirit of the rules for setting the aromatic flag. It's possible that the question was misunderstood, but I don't think so because this view was also expressed during the OpenSMILES discussions. Consider this passage from the mailing list:

… Dave [Weininger] seems to be emphasizing canonicalization in answering this question [about the purpose of the aromatic flag, quoted earlier], but having worked with him for six years, I heard him explain aromaticity many times, and the purpose was not for canonical SMILES. It was, as this quote says, to reflect the underlying uniformity of the bonds in aromatic systems (Dave calles [sic] it "symmetry" in this quote, but that's a bit inaccurate). Canonical SMILES are just one reflection of that underlying uniformity.

The problem with an ambiguous specification is that it encourages, even forces, users and software developers to find their own meaning.

All of which brings us to interpretation — in particular the assignment of implicit hydrogens. The aromatic flag can directly influence implicit hydrogen count. For example, the rules for computing atomic hydrogen counts in benzene (c1ccccc1) are different from the rules for computing atomic hydrogen counts in cyclohexane (C1CCCCCC1). In the former case, we must account for one implicit degree of unsaturation. The math happens to be easy in the case of benzene vs. cyclohexane. But disagreements about the meaning of the aromatic flag (or lack of explicit guidance around how to process it) will lead to different hydrogen counts in the more complex cases likely to be seen in the wild.

Conclusion

Hückel's rule has served chemistry well, but it is poorly-suited as the foundation for assigning and interpreting the SMILES aromatic flag. Until this situation is corrected, it will be impossible to describe SMILES at the level of detail needed for high compatibility across software implementations. Fortunately, it's possible to replace Hückel's rule with an alternative better suited to the demands of a molecular representation format.