Delocalization-Induced Molecular Equality

Molecular representation underpins all of cheminformatics and, arguably, chemistry itself. Getting molecular representation right is hard because it supports so many applications, and because all forms of molecular representation have limitations. When a molecular representation system finds its way into applications for which it's underqualified, the result can range from annoying to catastrophic. Today's article describes a phenomenon responsible for many mispairings of representation with application.

Bonding in Cheminformatics

Although molecular structure can be misrepresented in many ways, an especially rich source of errors is bonding. Cheminformatics draws most of its ideas about bonding from the valence bond (VB) model. This model views a bond as the interaction between two atoms and 2n electrons, where n is a positive integer. Cheminformatics adapts this idea by representing molecules as graphs onto which atom/bond electron counts are overlaid. As a result, the formal bond order computed across any edge in a VB graph will be a positive integer.

George Box famously observed that "All models are wrong, but some are useful." It doesn't take much effort to understand that the VB model is wrong. However, it can take a lot of effort to understand just how wrong the VB model can be, and when and why it isn't useful. I'll focus on the VB model, but it's important to keep in mind that any molecular representation system will necessarily be limited and therefore wrong in the right context.

Delocalization

What the VB model fails to account for is electron delocalization ("delocalization"). Delocalization is the phenomenon in which the electrons of a VB representation can be distributed over more than one bond, among two or more atoms, or across some combination of atoms and bonds. Several lines of experimental evidence are consistent with electrons exhibiting this escapist behavior. Electron delocalization is often referred to as "resonance," but this term has a long, complicated, confusing history. To avoid ambiguity I use the term "electron delocalization" instead of "resonance."

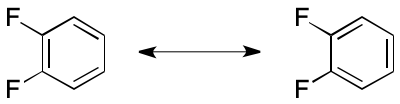

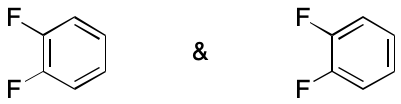

Electron delocalization crops up in many contexts, with one of the most important being "aromaticity." Consider 1,2-difluorobenzene. A VB graph would represent the cycle as alternating single- and double bonds. This representation is often called a "Kekulé structure." The problems start with the realization that 1,2-difluorobenzene can be represented by not one, but two unequal molecular graphs due to electron delocalization. An application such as structure search that failed to account for multiplicity of graphs could yield misleading results.

Delocalization is a necessary but insufficient condition for this effect. Consider fluorobenzene. It also undergoes delocalization, but a single molecular graph suffices. Here the graph's overall symmetry leads to equality of both candidate graphs.

It's pretty clear that electron delocalization is an artifact of the VB model. As noted by William Jensen in 2006:

It should be noted that use of resonance structures in connection with qualitative Lewis diagrams has long been known to be an artifact of an impoverished chemical symbol- ism and the conventions used to link that symbolism to the components of a simple wave function. The single line used to connect two atoms denotes an equally shared 2c–2e bond in which both atomic centers contribute equally to the wave function. Any deviation from this ideal requires the use of resonance, whether due to bond polarity (ionic-covalent reso- nance), multicentered bonding (bond–no bond resonance), nonintegral bond orders (single bond–multiple bond reso- nance), or so-called hypervalence (bond–lone pair resonance). The moment one agrees on a new valence symbol, such as the Y used to denote the localized 3c–2e bonds in the boron hydrides or the circle inside the benzene ring, and agrees on its relationship to the corresponding wave function, the quali- tative need for 2c–2e bond resonance evaporates. Likewise, as Harcourt showed many years ago, if we did not have the line to represent a 2c–2e bond, but only a dot to represent a single shared electron, we would have to use resonance of these dot formulas to represent conventional 2c–2e bonds as well. …

Artificial though it may be, cheminformatics can't ignore the fact that delocalization can have important practical consequences.

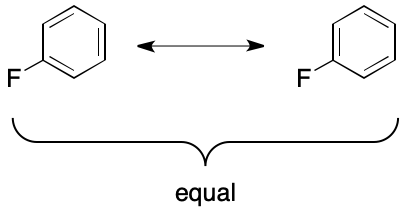

Aside: Molecular Equality

The term "unequal" has a specific graph theoretical meaning here. Molecules are represented as graphs, affording access to a rich set of tools for graph comparison. One of them is "isomorphism." Isomorphism is an operation that seeks a 1:1 mapping between the features of a query and target graph. But depending on who you ask, this mapping either does or does not account for node and edge labels. For example, the molecular graphs for cyclohexane and cyclohexene might or might not be considered isomorphic. Confusion can be avoided by using the term "equal" to refer to two graphs that are isomorphic with respect to node and edge labeling.

Delocalization-Induced Molecular Equality

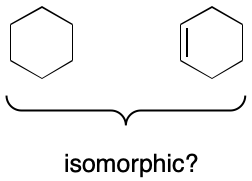

Electron delocalization can be brought closer to the realm of cheminformatics as something I'll call delocalization-induced molecular equality (DIME). DIME occurs when a molecule can be represented by two or more graphs differing only in the distribution of electrons among atoms and/or bonding relationships. If a single graph adequately represents electron distribution, it will not be capable of DIME.

A molecule exhibiting DIME will be associated with two or more contributing graphs. A contributing graph is a molecular graph that encodes a unique electron distribution over its nodes and edge. The properties of a molecule can best be described as a superposition of its contributing graphs. Contributing graphs must be treated as equal despite their inequality.

Although the terms "electron delocalization," "resonance," "mesomerism," "mesomer," "hyperconjugation," and "resonance form" might seem suitable for describing this phenomenon, these terms lack a foundation in graph theory. Worse, they have been the subject of intense debate over several decades in chemistry. But the most important reason to reject these overloaded terms is that none of them completely describes the phenomenon. Choosing unique terms grounded in graph theory eliminates confusion and ambiguity while enabling succinct discussion.

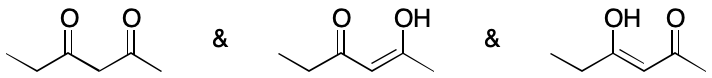

The distinction between tautomerism, which is considered an equilibrium process, and other phenomena such as aromaticity is of great theoretical and practical importance in chemistry. So much so that each uses different notation (an equilibrium arrow for tautomerism and a double-headed arrow for everything else). But from the perspective of information systems, this distinction offers little to justify the overhead. What matters with respect to DIME is that a given molecule can be represented by two unequal molecular graphs that must be treated as if they were equal. To emphasize this point, contributing graphs are separated by the ampersand symbol (&) rather than an arrow. For those cases in which the distinction matters, an information system can provide metadata to indicate the chemical phenomenon involved.

The Many Faces of DIME

DIME encompasses a wide range of chemical phenomena, some of which have no name and some of which have many names. What they all have in common is that the molecules in question can't be adequately described by a single molecular graph. Beyond this distinction, instances of DIME are too numerous to catalog here. Several reviews on the topic from a variety of perspectives are available, including:

- So you think you understand tautomerism

- Toward a Comprehensive Treatment of Tautomerism in Chemoinformatics Including in InChI V2

- A simple approach to the tautomerism of aromatic heterocycles

- The Nature of the Chemical Bond

What follows are some examples that illustrate the circumstances in which DIME might come into play.

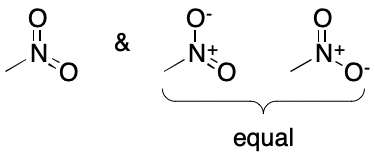

The nitro group is a common cause of DIME. Two contributing graphs are usually considered. It should be noted that symmetry ensures there will only be one charge-separated contributing graph. Furthermore, systems that normalize graphs to either pentavalent nitrogen or charge separated forms will not be subject to DIME. Isotopic substitution on oxygen would of course bring DIME back into play for the charge-separated form.

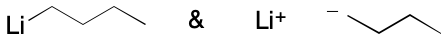

Organometallics offer a rich source of material for exploring the limits of the VB model. Many examples relate to multi-center bonding (e.g., diborane), and in many of these cases fractional bond orders of one or greater are involved. However, many problems are caused by contributing graphs in which a bond order of zero or one is computed across an edge. An example is butyllithium, a molecule likely to be present in many chemical databases due to its widespread use in synthetic organic chemistry.

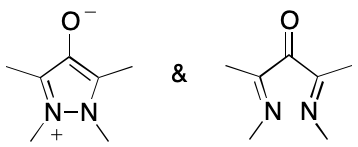

But this charge-separated variety of DIME is not limited to molecules containing metals. Consider the betaine below. Here the contributing graphs differ in that one is cyclic whereas the other is not. The situation is further complicated by the possibility of geometric isomerism about the carbon-nitrogen double bond.

Many examples of DIME fall under the nebulous heading of "aromaticity." In the broadest sense, aromaticity ascribes special symmetry, energetic, geometrical, electronic, and reactivity properties to molecules with certain cyclic electron bond patterns. A case in point is 1,2-difluorobenzene, which was discussed in the previous section. Countless other examples are known.

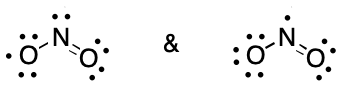

Nitrogen dioxide is an interesting example of DIME because it illustrates how contributing graphs can differ by virtue of placement of an electron within a bond or on an atom.

Many examples of DIME fall under the heading of tautomerism. Like aromaticity, this is a hard concept to pin down. Wikipedia defines tautomerism in a manner consistent with how many chemists would view about the issue:

Tautomers are structural isomers (constitutional isomers) of chemical compounds that readily interconvert.

My informal Twitter poll shows that most respondents view tautomerism and resonance to be separate phenomena.

Resonance and tautomerism are different things.

— Rich Apodaca (@rapodaca) June 15, 2021

Keto-enol tautomerism is a well-documented phenomenon in organic chemistry. The main difference between tautomerism and other forms of DIME is that the designation "tautomer" implies that contributing graphs undergo equilibrium. As the next section will explore, however, in many contexts this distinction is of no practical consequence.

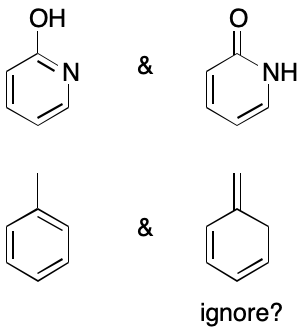

God in the Gaps

Whether or not DIME should be considered depends in large part on the observability of its effects. If the effects of a contributing graph can't be observed under some set of relevant conditions, should it be considered? Typically, discussions of this question revolve around tautomers. For example, toluene and 2-pyridone can each be represented as a set of contributing graphs that would be considered tautomers. However, 2-pyridone is most commonly represented by two contributing graphs whereas toluene only one. The difference in each case comes down to observability. Just because a contributing graph is feasible doesn't mean it needs to be used.

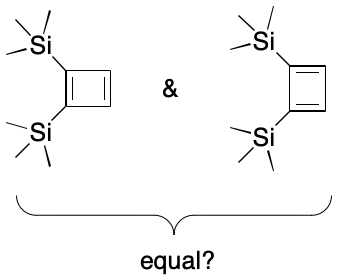

Observability also plays a role in cases that don't involve tautomerism. Consider cyclobutadiene. As an "antiaromatic" 4n system, the contributing graphs for 1,2-disubstituted cyclobutadienes should in principle be distinguishable experimentally. However, the difficulty of synthesizing, let alone observing such molecules raises questions about whether a cheminformatics system should treat 1,2-substituted cyclobutadienes in the same way it treats 1,2-disubstituted benzenes.

Observability implies observations, but cheminformatics systems often deal with molecules having little in the way of analytical or reactivity data. Exactly how eagerly should contributing graphs for new molecules be sought out? To what extent do observations of relatively unsubstituted molecules apply to more complex analogs? What roles do solvent, temperature, pressure, and timescale play in observability and should that be taken into account? The only universal answer to these questions is "it depends."

The most logical guidance is to account for the ways in which a cheminformatics system will be used. If ignoring a contributing graph has no downstream consequences, then it can be ignored. Unfortunately, it may be impossible to make this prediction.

Some Problematic Applications

DIME plays a role in many cheminformatics settings. One class of problems relates to graph isomorphism. Although there are many many approaches, they differ mainly in the ways they optimize the same basic central brute-force procedure. In a nutshell, this procedure exhaustively compares the nodes and edges of a query graph to the nodes and edges of a target graph until a complete mapping is found. No polynomial time algorithm for this process is known, making molecular comparisons potentially very expensive.

A solution to this problem is canonicalization. Canonicalization the process of choosing one representation out of more than one possibility. A molecular graph can be canonicalized through an algorithm that deterministically selects the same unique ordering of nodes and edges. Given such a graph, it's easy to compare two molecules for equivalence. Just transform each into its canonical representation. If the two are identical, so are the molecules. Molecular graphs are often encoded in string-based formats, and when this is the case the problem of determining molecular equality reduces to string comparison, which is highly efficient.

However, canonicalization is based on the assumption that a single unique graph can represent any molecule. If that assumptions doesn't hold due to DIME, other factors must come into play, as described in the next section.

Beyond canonicalization lie other kinds of molecular comparison. For example, substructure search brings with it similar considerations as exact structure search and canonicalization. Namely, it's crucial to address the possible existence of multiple contributing graphs.

Fingerprints and descriptors are further applications in which DIME can play a role. These are usually implemented by hashing molecular fragments. If no attempt is made to address the possible existence of contributing graphs for an input structure, then it's possible to obtain two different results for the same molecule.

Solutions

At least two conceptual approaches are open for dealing with DIME:

- Use a representation that subsumes contributing graphs through symmetry.

- Deterministically select one contributing graph.

Examples of (1) can be found in SMILES and InChI. SMILES augments the VB model with an atomic aromaticity flag. This makes it possible to eliminate certain contributing graphs involving electronic conjugation around a cycle. InChI addresses tautomerism with "mobile hydrogens," which allow hydrogens involved in tautomerism to be associated with multiple heavy atoms simultaneously.

Although these steps mitigate problems cause by DIME, they can't completely eliminate them. SMILES does nothing to address tautomerism and so requires users of canonical SMILES to pick one. An the availability of the aromaticity flag does nothing to address the question of whether "antiaromatic" cycles should be encoded as aromatic. For its part, InChI only perceives some forms of tautomerism and so requires similar decisions.

A variation on (1) is to deal with DIME by removing features from a representation system. For example, InChI captures the connectivity between atoms but says nothing about electron distribution. In doing so, InChI makes it impossible to even express many forms of DIME. A similar approach can be used in exact- and substructure search, and when computing molecular descriptors.

There are many cases in which (1) is not feasible. For example, Molfile is a widely-used format with no ability to alleviate DIME through symmetry reduction. (An "aromatic" bond is supported, but its use is restricted to molecular queries.) It's still possible to canonicalize molfiles, but applications such as canonicalization would need to choose among the available contributing graphs.

In practice, no information system is likely to be immune to the effects of DIME. At some point a molecule or molecule/environment pair will be encountered that requires two or more unequal molecular graphs to be treated as if they were equal. It's also possible that countermeasures against DIME could come to be viewed as overly aggressive, preventing users from distinguishing experimentally distinguishable forms.

Conclusion

Delocalization-induced molecular equality (DIME) can be found throughout cheminformatics. DIME makes its presence known by the failure of a single graph to adequately represent a given molecule. The language developed around this phenomenon in chemistry has limited utility in cheminformatics. This article presents a graph-based foundation for describing the effects of resonance, mesomerism, tautomerism, valence bond isomerism, aromaticity, and related chemical phenomena in information systems. Knowing how and why DIME can occur, and when its presence matters, are crucial to addressing chemistry's complexities. It may not be possible to fully eliminate DIME, but its effects can be mitigated.