Multi-Atom Bonding in Cheminformatics

Over the last several decades, cheminformatics has managed to produce a few dozen different ways to exchange molecular encodings and metadata. Despite ongoing experimentation with high-level encoding techniques, these formats are mostly devoid of new ideas around bonding. To the extent that bonding relationships are encoded at all, they occur almost universally as the union of exactly two atoms. This narrow focus finds its way into the major cheminformatics toolkits and ultimately user-facing tools.

Chemists for their part have ignored the cheminformaticians completely. Over the last 70 years, chemists across disciplines have created a dizzying array of stable substances for which a two-atom bonding model is not only inconvenient, but downright wrong. Multiple Nobel prizes have been awarded for work featuring stable species flouting the bonding norms of cheminformatics.

This article takes a closer look at cheminformatics' two-atom bonding fixation, some consequences, and a solution.

The Two-Atom Model of Bonding

The two-atom model of bonding traces its roots to valence bond theory. But in terms of graph theory, a two-atom bond is just a labeled edge of a molecular graph. Toolkits and file formats differ on what to call these edge labels, their syntax, and their semantics. In SMILES, a bond is an edge labeled with a "type" property that can assume the values: blank; colon (:); hyphen (-); equals (=); octothorpe (#); dollar ($); forward slash (/); and backslash (\). In molfiles, a bond is an edge labeled with a "type" property (values 1, 2, or 3) and a "stereo" property (values 0, 1, 3, 4, and 6). In many cheminformatics toolkits, a bond is an edge labeled with an "order" property that assumes a positive floating-point values.

More broadly speaking, the two-atom bond in cheminformatics serves as an anchor for two properties: (1) a bond order; and (2) a stereo descriptor. I'll discuss stereo descriptors in detail later. For now, let's focus on bond order.

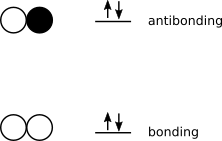

As noted previously, bond order is a computation, not an attribute. This means that it should be derived from one or more attributes. A more robust, but rarely-used, statement of the two-atom model would associate an electron count attribute with an edge. Bond order can then be computed as one-half the electron count. A single bond contains two electrons, a double bond four, and so on. From this perspective, zero-order bonds seem reasonable as well.

It's not hard to understand the reluctance of cheminformatics to embrace multi-atom bonding. Two-atom bonding is relatively easy to implement. Few common tools support multi-atom bonding. But it turns out that chemistry doesn't care about any of that.

Practical Consequences

From 2007-2008 I published a series of about 20 short posts highlighting experimental work with substances that could not be adequately represented using prevailing concepts of bonding (and stereochemistry) in cheminformatics. They were all titled How Would Your Cheminformatics Tool Do This? (example). Others have noted similar limitations, to varying degrees, before and since.

At the center of it all lies the two-atom bonding model, which is insufficient for representing large swaths of chemistry today. The problems are many, but often take the form of symmetry artifacts. Atoms that are clearly equivalent become artificially differentiated when two-atom bonds must be used. Additionally, two-atom bonds may lead to hydrogen and electron miscounts.Consider these cases:

- Organometallics. These species span a wide range of complexity. At one end, simple boranes feature three-centered, two-electron boron-hydrogen-boron bonds. At the other end, borane and other metal clusters feature molecular orbitals spanning many atoms. In between are metallocenes, various π-allyl species, and a variety of others.

- Aromaticity. Benzene and naphthalene are well-known examples of this very large class. But we don't need to stray far before problems arise. Take the cyclopentadienyl anion or cyclopropenium ion for example. Two-atom bonds fail utterly to capture the symmetry of these species. More broadly, we can find numerous examples of acyclic electron delocalization starting with the humble allyl radical.

- Tautomers. The flip-side of electron delocalization is hydrogen delocalization. Tautomers arise from electron shifts capable of capturing or releasing atoms, typically hydrogen. The phenomenon can be seen in numerous molecules in common use, many of which feature prominently in the pharmaceutical industry.

Now consider the practical consequences. In 2017, a team working with the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Center collection reported that out of a subset of about 500K entries, InChIs could be successfully generated for just 100K. Half of these were categorized as "not organic." A similar effort using SMILES with the Crystallography Open Database resorted to a series of conventions to deal with organometallic bonding. Meanwhile, the lack of formats capable of representing aromaticity has lead (and will likely continue to lead) to conversion errors. Although InChI has done a lot to alleviate the problem of accounting for tautomeric forms in chemical registration systems, there's plenty of work still to be done.

Bonding System

A way forward was proposed in 1997 by Andreas Dietz. Contrary to other work in this area, Dietz didn't exactly propose something new so much as extend the same two-atom bonding concept used in cheminformatics from the beginning.

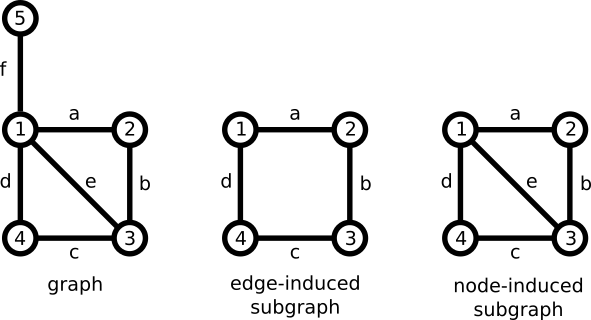

The proposal considers a bond, not as a labeled edge, but rather a labeled, edge-induced subgraph. A subgraph is a graph that shares some of the nodes and some of the edges of another graph. An edge-induced subgraph contains some of the edges of the original graph, but all of the endpoints. This contrasts with a node-induced subgraph, which contains a subset of nodes, but all of the edges connecting them.

Dietz brought these concepts together with the bonding system. Like a two-atom bond, a bonding system carries metadata. In particular, a bonding system has an attribute representing an electron count.

From this perspective, we can see that a two-atom bond with an electron count attribute is nothing more than a special case of bonding system. In other words, bonding systems can be backward-compatible with two-atom bonds. Unfortunately, Dietz didn't emphasize this point strongly enough.

Backward-compatibility brings substantial practical advantages. The most important of these is phased implementation. A file format or cheminformatics toolkit can start out supporting only two-atom bonding. Later on, it can be extended to support arbitrary multi-atom bonding. The catch is that the starting point must never introduce functionality that will later become incompatible with multi-atom bonding. I recently described a suitable starting point and will have more to say about retrofitting in later posts.

Formal Bond Order

To make the backward-compatibility of bonding systems more concrete, consider formal bond order. Formal bond order represents the number of electrons shared by each of the terminals of an edge in a molecular graph. A formal bond order of one implies one shared electron per terminal, a formal bond order of two implies two shared electrons, and so on. As noted previously, the bond order of a two-atom bond is simply the electron count divided by two.

Bond order computations over bonding systems follow a similar pattern. As detailed in the next section, however, a given edge can participate in zero, one, or more bonding systems. The account for this freedom, the following relationship for the formal bond order between atoms and is used:

where:

- is the set of bonding systems containing the edge

- is a bonding system

- is the number of electrons in bonding system

- is the number of edges in bonding system

Two-atom bonds are merely a special case. Consider ethane. Its only C-C bond can be represented by a one-edge bonding system. Using the equation above, we note that this bonding system has two electrons () and one edge (). The formal bond order of the C-C bonding system in ethane is then given by:

As expected, this is a single bond.

Now consider the allyl radical. It can be considered to have three heavy-atom bonding systems. Two of them are represented as traditional two-electron, one-edge C-C bonds. The third is a three-electron, two-edge bond (, ). It follows that the formal bond order over either edge in the allyl radical is:

Note that we get the same answer if we model the allyl radical with two extended bonding systems. For example, two electrons could be associated with a two-edge bonding system, and a third electron could be associated with a separate two-edge bonding system:

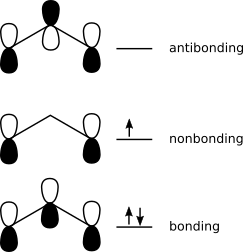

Either way, a formal bond order (7/4) may seem odd from the perspective of molecular orbital theory, which would predict two-electron occupancy of a bonding MO with single occupancy of a non-bonding orbital. Doesn't the bonding system approach overstate the "real" bond order?

A similar situation arises with any toolkit that allows species such as dihelium (SMILES; [He]=[He]). Despite a formal bond order of two, dihelium displays a fleeting existence experimentally. MO theory predicts a bond order of zero, which is consistent with experimental evidence.

[He]=[He].

Formal bond order, regardless of context, should be viewed more as an electron accounting tool rather than a representation of reality. This caveat applies regardless of whether multi-atom bonding is being used.

Notation

To prepare for more specific examples, some new notation will be needed. Rather than verbose English-language descriptions, it's more convenient to use a compact shorthand.

Dietz proposes a notation based on a non-empty edge set, raising the question of connectedness. A graph is said to be connected if a route can be traced from any node to any other node through an alternating path of edges and nodes. But an edge set can generate a disconnected subgraph. Must bonding systems be based on connected subgraphs? All of the examples presented by Dietz are connected, but no requirement is stated.

Given that disconnected bonding systems appear to have no application, it's best to disallow them. Our notation system can enforce this rule by replacing the edge set with a representation of a traversal.

Just such a system has been in use for many years now in the form of the InChI connectivity layer, itself based on SMILES. With this as the starting point, here's a procedure for generating a simple bonding system notation:

- Assign each atom in the molecular graph an integer index starting with one.

- Identify the connected subgraph underlying the bonding system

B. - Perform a depth-first traversal over

Bstarting with any of its nodes. - For each node traversed, write its index determined in step (1).

- Wrap any branch in parentheses (

(and)). - Separate other node-node traversals with a hyphen (

-). - When closing a cycle, repeat the node index determined in step (1).

- Append the string with a colon (

:) followed by the electron count. - Wrap the entire string in curly braces (

{and}).

Consider again the allyl radical. Starting with a primary carbon, we number the nodes sequentially from 1-3, inclusive. Traversing the bonding system subgraph and assigning an electron count yields:

{1-2-3:3}

As another example, consider benzene. Its π-system can be represented as a bonding system comprised of a six-edge cyclic subgraph and six electrons:

{1-2-3-4-5-6-1:6}

Examples

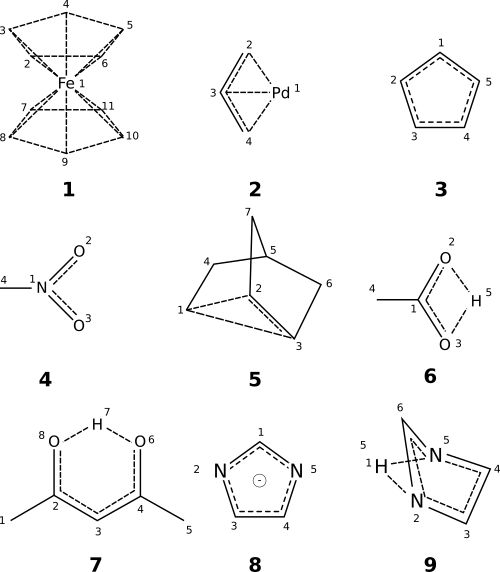

A few examples of the ways in which bonding systems can be used are depicted above. Example notations follow:

- ferrocene.

{2(1)-3(1)-4(1)-5(1)-6(2)-1-7-8(1)-9(1)-10(1)-11(1)-7:12} - π-allyl palladium chloride dimer.

{1-2-3(1)-4-1:3} - cyclopentadienyl anion.

{1-2-3-4-5-1:6}1 - nitro group.

{1(2)-3:3} - norbornyl cation.

{1-2-3-1:2} - acetic acid.

{1-2-5-3-1:4} - acetylactetone.

{2-3-4-6-7-8-2:6} - imidazole anion.

{1-2-3-4-5-1:6} - imidazole alternative.

{1-2-3-4-5(1)-6-2:6}

As these examples illustrate, multi-atom bonding systems are well-suited to eliminating artificial symmetry and preserving electron counts. The role is similar to that played by aromaticity in SMILES, and mobile hydrogens in InChI. But unlike aromaticity, bonding systems can be used without ambiguity because all electron counts are fully specified. Nor do bonding systems overload an already-controversial term used in chemistry. Finally, bonding systems need not overlap the sigma bonding framework (for example, 1, 2, 5, 6, 7, and 9).

Like any tool, bonding systems can cause harm through misuse. A case in point is structure 9. Inclusion of the hydrogen atom within an extended bonding system framework eliminates artificial symmetry that would otherwise be induced by two-atom bonding representations. However, this approach can lead to non-intuitive conclusions. Depending on the application, the alternative imidazole anion 8 might be more appropriate. Each option communicates something different. As Dietz observes:

Note that a molecular structure representation cannot free the user from the task to decide how a chemical structure should be represented. However, a lack of versatility might force the user to represent a chemical structure in a certain manner, even if he actually would prefer to represent it differently.

Conclusion

Multi-atom bonding appears in many areas of chemistry. The entrenched cheminformatics convention of two-atom bonding is inadequate when faced with chemistry's full repertoire. Multi-atom bonding offers a solution that can be implemented in a backward-compatible way.