SMILES Formal Grammar

Three line notations find regular use in cheminformatics: SMILES; InChI; and IUPAC nomenclature. Of these three, only SMILES finds widespread use in machine-to-machine chemical structure exchange. That role depends on a set of well-defined syntactic rules. This article enumerates those rules using a formal grammar. Those familiar with the concepts behind formal grammars can skip to the end of the article, where a full SMILES grammar is presented.

Formal Grammar

Wikipedia defines formal grammar (aka "grammar") as a tool that reveals:

… how to form strings from a language's alphabet that are valid according to the language's syntax. A grammar does not describe the meaning of the strings or what can be done with them in whatever context—only their form. A formal grammar is defined as a set of production rules for strings in a formal language.

In other words, a grammar enumerates all of the rules for producing valid strings in some language. At the same time, a grammar says nothing about what those strings mean.

A grammar serves as a concise, comprehensive guide to a language. Beyond that, a grammar serves as a blueprint for writing a parser by hand. More interestingly, a grammar can be used as a template for machine-generated parsers.

LL(1) Grammars

Grammars have been the focus of much computer science research over the years. Some of that research has been devoted to categorizing languages by the kinds of grammars they produce. SMILES syntax can be expressed as an LL(1) grammar.

LL(1) grammars can be parsed using a technique I call Scanner-Driven Parser Development. To recap, an object of type Scanner encapsulates a string to be parsed through an API with three methods:

cursorreturns the index of the cursorpeekreturns the character at the cursorpopreturns the character at the cursor and increments the cursor

Using a Scanner instance, a parser iterates one character at a time from a string. At each iteration, the parser has only one path open to it depending on the value returned from peek. As a result, the functions composing the parser assume the structure of the grammar itself. The result is known as a recursive descent parser. One of the most powerful features of such parsers is the lack of backtracking, which ensures a linear relationship between parse time and the number of tokens.

Weininger on SMILES Grammar

Dave Weininger, SMILES' creator, wrote a description of the SMILES grammar in 2008. Although his exact formalisms won't be used here, many of his definitions and terms will.

In a noteworthy passage, Weininger described the SMILES grammar as follows:

The formal grammar of the SMILES language is in a class of grammars (called “LR-1”) [sic] which is parsable with extreme efficiency and can be processed as a stream. One never needs to “back up” to figure out what is being represented.

Weininger's characterization of the SMILES grammar as LR(1) ("LR-1") may seem at odds with mine (LL(1)). Generally, the set of LR grammars encompasses the set of LL grammars so there's no inconsistency. One way to view the distinction is through the corresponding parser implementations. Both can be thought of as producing traversals over a tree. Whereas LR(1) parsers produce post-order traversals, LL(1) parsers produce pre-order traversals. For details, see this article. The bottom line is that LL(1) grammars are much simpler to parse than LR(1) grammars.

Expressing Grammar

Like any grammar, the one we'll define for SMILES is composed of a set of production rules. A production rule (or just "production") defines a specific string transformation allowed by the grammar. In other words, a production rule can be thought of as a named string transformation.

Over the years, several systems for representing grammars have been developed. One of the most popular is Backus–Naur form (BNF). This notation will be used throughout this article.

A production expressed in BNF consists of three parts. First, the name of the rule is given. Sometimes, angle brackets wrap the name and sometimes they don't. I'll be using angle brackets for the widest compatibility with automated tools. Next, an assignment operator appears. Apparently, =, :=, and ::= are all valid, although the most broadly-supported is ::=. Following the assignment operator are one or more terminals and nonterminals.

A non-terminal is the name of a rule. These names appear on the left-hand side of the assignment operator for a given production. In other words, a non-terminal appearing on the right-hand side of the assignment operator can always be found as the name of some production rule elsewhere in the grammar.

A terminal is an irreducible element of the language. In the case of SMILES, terminals include characters such as open parentheses ((), close parentheses ()), letters, and numbers.

For example, consider a production rule for an explicit bond in SMILES. It can be expressed as follows:

<bond> ::= "-" | "=" | "#" | "$" | "/" | "\\"

Similar to regular expressions, the items in a list of alternatives are separated by the pipe symbol (|). The production rule called <bond> is satisfied by any of the six enumerated characters. Notice that <bond> does not include the dot (.) operator. The reason is that dot is not a bond at all. Rather, dot indicates the absence of a bond. Our grammar will include it as a separate production.

As a more advanced example, consider the production for atomic charge in SMILES. We'd like to allow atoms to assume any integer charge from -15 to -1, inclusive, and from +1 to +15, inclusive. Additionally, we'd like to support the shorthand forms + (+1), ++ (+2), - (-1) and -- (-2). All other charges, including nonsensical forms such as +0, -0, should be disallowed. The following production satisfies the requirements.

<charge> ::= "+" ( "+" | <fifteen> )? | "-" ( "-" | <fifteen> )?

<fifteen> ::= "1" ("0" | "1" | "2" | "3" | "4" | "5")?

| ( "2" | "3" | "4" | "5" | "6" | "7" | "8" | "9" )

The <charge> rule is defined in terms of a second rule, <fifteen>. Both rules acting together yield the desired behavior. Optionally, the <fifteen> production could be inlined into <charge>. However, the result would be unwieldy and hard to understand.

Like computer programs, grammars can (and should be) refactored for clarity and performance.

Playing with Grammars

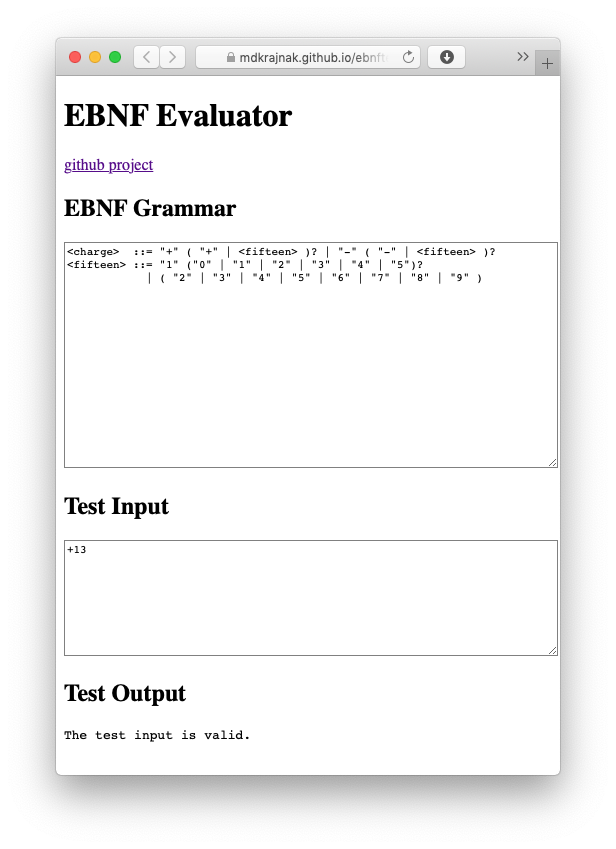

One of the best ways to understand the core ideas around formal grammars is to use them. An easy way to do that is through online tools. I've found one in particular to be both convenient and helpful.

Browse over to EBNF Test. This web page hosts an automated grammar parser and compiler. Given an grammar in EBNF form and a test string, the EBNF Evaluator will tell you (a) if the grammar compiled; and (b) whether the test string is valid.

Copying the production rules <charge> and <fifteen> above yields a parser that can distinguish valid and invalid SMILES charges.

The OpenSMILES Grammar

The OpenSMILES specification defines a formal grammar for SMILES. It's a good starting point for studying the language. In its current form, however, there's room for improvement. For example:

- Not LL(1). Left recursion in the

chainproduction means that the OpenSMILES grammar can't be used as a blueprint to write a hand-crafted recursive descent parser. Worse, many tools will reject such grammars outright, so automated parser generation will also not be feasible. Fortunately, left-recursion is unnecessary in SMILES, as will be demonstrated later in the article. - Imprecise. The OpenSMILES grammar supports charges from -99 to +99, inclusive, contradicting the written description.

- Missing element symbols. Several new element symbols were adopted since the publication of the OpenSMILES formal grammar. It seems reasonable to include them now.

- Overinclusive. The OpenSMILES grammar supports uncommon forms of template-based stereochemistry. It might be better to leave those forms as extensions, and instead support just the two universally-used forms:

@and@@. Similarly, the wildcard atom (*) might be better defined as an extension rather than a core language component.

Combining the above points with the original OpenSMILES specification yields a good starting point for developing a new SMILES grammar.

A Toy Grammar

We can think of a SMILES as a single line of text encoding at least one atom with possibly more following the first. These atoms can grouped into branches or chains of atoms optionally connected by a bond or dot (.). Additionally, cycles can be encoded with cuts represented as numerical indexes ("rnum"). These ideas are captured in the toy grammar shown below.

<line> ::= <atom> ( <chain> | <branch> )*

<chain> ::= ( <dot> <atom> | <bond>? ( <atom> | <rnum>) )+

<branch> ::= "(" ( ( <bond> | <dot> )? <line> )+ ")"

<rnum> ::= <digit> | "%" <digit> <digit>

<atom> ::= "X"

<bond> ::= "-" | "=" | "#" | "$" | "/" | "\\"

<dot> ::= "."

<digit> ::= "0" | "1" | "2" | "3" | "4" | "5" | "6" | "7" | "8" | "9"

In this language, the only allowed atomic representation is "X". In every other respect, this language is identical to the complete SMILES grammar.

We can test this grammar by adding it to the BNF Test website. The following strings are valid, as expected:

X

X(X)

X(X)X

X-X(-X)

X1X(XXX1)X

X.XX(=X)X

Misplaced bonds (e.g., X==X), unbalanced and empty parentheses (e.g., (), X(X(X)), and invalid rnums (e.g., X?XX?) are all automatically detected as invalid.

One noteworthy limitation of this approach is rnum matching. The grammar can't detect unbalanced rnums; this kind of validation transcends syntax and must be handled at the level of semantics. The same limitations apply to any SMILES grammar, and more generally will apply to any one-character lookahead grammar.

Atoms

Looking past the basic structure of the SMILES grammar, the most notable feature is the many options for representing atoms. The previous toy grammar defined the following <atom> production rule:

<atom> ::= "X"

SMILES supports two forms of atoms: organic symbol and bracket atom.

An organic symbol must be a member of the so-called "organic subset". The organic subset consists of the following elements: "B"; "C"; "N"; "O"; "P"; "S"; and the halogens. Additionally, the following aromatic symbols may appear as organic symbols: "b"; "c"; "n"; "o"; "p"; "s". The set of all possible organic symbols can be formulated as:

<organic_symbol> ::= "B" "r"? | "C" "l"? | "N" | "O" | "P" | "S"

| "F" | "I" | "At" | "Ts"

| "b" | "c" | "n" | "o" | "p" | "s"

A bracket atom is an atomic symbol with optional properties surrounded by left and right brackets ([ and ]). Available properties include: isotope; hydrogen count; charge; stereo flag; and map. The latter is a user-definable three-digit numerical identifier.

<bracket_atom> ::= "[" <isotope>? <symbol> <chiral>? <hcount>? <charge>

| <map>? "]"

<symbol> ::= "C"

<hcount> ::= "H" <digit>?

<charge> ::= "+" ( "+" | <fifteen> )? ) | ( "-" ( "-" | <fifteen> )?

<isotope> ::= <digit>? <digit>? <digit>

<digit> ::= "0" | "1" | "2" | "3" | "4" | "5" | "6" | "7" | "8" | "9"

<fifteen> ::= "1" ("0" | "1" | "2" | "3" | "4" | "5")?

| ( "2" | "3" | "4" | "5" | "6" | "7" | "8" | "9" )

<map> ::= ":" <digit>? <digit>? <digit>

For simplicity, the <symbol> production is truncated here and only contains an entry for carbon ("C"). The full grammar at the end of this article contains the complete set of IUPAC-defined atomic symbols.

Putting It All Together

The two rules <organic_symbol> and <bracket_atom> can be combined into a new production called <atom>:

<atom> ::= <organic_symbol> | <bracket_atom>

Replacing the old rule for <atom> in the toy grammar with this new one yields a complete LL(1) SMILES grammar:

<line> ::= <atom> ( <chain> | <branch> )*

<chain> ::= ( <dot> <atom> | <bond>? ( <atom> | <rnum>) )+

<branch> ::= "(" ( ( <bond> | <dot> )? <line> )+ ")"

<atom> ::= <organic_symbol> | <bracket_atom>

<bracket_atom> ::= "[" <isotope>? <symbol> <chiral>? <hcount>? <charge>?

| <map>? "]"

<rnum> ::= <digit> | "%" <digit> <digit>

<isotope> ::= <digit>? <digit>? <digit>

<hcount> ::= "H" <digit>?

<charge> ::= "+" ( "+" | <fifteen> )? | "-" ( "-" | <fifteen> )?

<map> ::= ":" <digit>? <digit>? <digit>

<symbol> ::= "A" ( "c" | "g" | "l" | "m" | "r" | "s" | "t" | "u" )

| "B" ( "a" | "e" | "h" | "i" | "k" | "r" )?

| "C" ( "a" | "d" | "e" | "f" | "l" | "m" | "n" | "o"

| "r" | "s" | "u" )?

| "D" ( "b" | "s" | "y" )

| "E" ( "r" | "s" | "u" )

| "F" ( "e" | "l" | "m" | "r" )?

| "G" ( "a" | "d" | "e" )

| "H" ( "e" | "f" | "g" | "o" | "s" )?

| "I" ( "n" | "r" )?

| "K" "r"?

| "L" ( "a" | "i" | "r" | "u" | "v" )

| "M" ( "c" | "g" | "n" | "o" | "t" )

| "N" ( "a" | "b" | "d" | "e" | "h" | "i" | "o" | "p" )?

| "O" ( "g" | "s" )?

| "P" ( "a" | "b" | "d" | "m" | "o" | "r" | "t" | "u" )?

| "R" ( "a" | "b" | "e" | "f" | "g" | "h" | "n" | "u" )

| "S" ( "b" | "c" | "e" | "g" | "i" | "m" | "n" | "r" )?

| "T" ( "a" | "b" | "c" | "e" | "h" | "i" | "l" | "m"

| "s" )

| "U" | "V" | "W" | "Xe" | "Y" "b"?

| "Z" ( "n" | "r" )

| "b" | "c" | "n" | "o" | "p" | "s" "e"? | "as"

<organic_symbol> ::= "B" "r"? | "C" "l"? | "N" | "O" | "P" | "S"

| "F" | "I" | "At" | "Ts"

| "b" | "c" | "n" | "o" | "p" | "s"

<bond> ::= "-" | "=" | "#" | "$" | "/" | "\\"

<dot> ::= "."

<chiral> ::= "@"? "@"

<digit> ::= "0" | "1" | "2" | "3" | "4" | "5" | "6" | "7" | "8" | "9"

<fifteen> ::= "1" ("0" | "1" | "2" | "3" | "4" | "5")?

| ( "2" | "3" | "4" | "5" | "6" | "7" | "8" | "9" )

The vast majority of space in this grammar is somewhat misleadingly dedicated to the 100+ elemental symbols. Stripping them out leads to the simpler toy grammar presented earlier.

Plugging the full grammar into EBNF Test yields a parser that can validate the syntax of any SMILES string given the parameters in this article.

Conclusion

A formal grammar is a powerful tool for human and machine use of language. This article presents a full-fledged SMILES grammar based on two that have been previously proposed. The main advantages of this new grammar are amenability to parsing by both hand-crafted parsers and a wide range of parser generators, and the detection of certain corner cases. Future articles will discuss some applications of this new grammar.