Hydrogen Suppression in Molfiles

Molfile is one of the most widely-used information exchange formats in cheminformatics. Like many formats and toolkits, the V2000 molfile format supports monovalent hydrogen suppression, meaning that hydrogens and bonds to them may exist despite their absence from the molecular graph. This capability raises questions around how exactly suppressed hydrogens should be read and written. This article documents the molfile format's peculiar and obscure, yet rigorous support for suppressed hydrogens.

Hydrogen Suppression

Hydrogen outnumbers every other element, including carbon, in many organic molecules. At the same time, nearly all hydrogens are monovalent, meaning that they connect to their parents through two-electron, two-atom bonds. These two properties, ubiquity and monovalence, have lead to the widespread and longstanding optimization called hydrogen suppression.

Hydrogen suppression is the practice of eliding hydrogens as nodes in a molecular graph. Effective use of hydrogen suppression demands robust methods for encoding and decoding hydrogen counts. A lot is at stake, as evidenced by the large number of molecular properties that depend on accurate hydrogen counts, including molecular weight, molecular formula, hydrogen bond donor count, and numerous descriptors and fingerprint schemes.

Two modes of hydrogen suppression are possible, each differing in how hydrogen count is reconstructed:

- Implicit Hydrogen. The hydrogen count is determined algorithmically.

- Virtual Hydrogen. The hydrogen count is encoded by an atomic integer attribute.

The molfile format supports both modes of hydrogen suppression, albeit idiosyncratically and somewhat covertly.

Authoritative Documentation

Two authoritative documents, both published by corporate sponsor BIOVIA, specify the molfile format:

- CTfile Formats. Describes V2000 molfile syntax.

- Chemical Representation Guide (aka "the Guide"). Describes V2000 molfile semantics and application-specific issues.

These two documents have lived very different lives. CTfile Formats is widely-known and readily available. However, it makes only passing mention of the Guide. The Guide, in contrast, has a history of obscurity. For a long time I was unaware of even its existence, which could be expected from a document that was only distributed to paying customers. This obscurity, coupled with lack of information about hydrogen suppression in CTfile Formats, has led to much confusion over the years. The most recent public version is available from current sponsor BIOVIA as Chemical Representation Guide 2017. I happen to own a newer revision, however, which is titled Chemical Representation 2018 SP1. Even more recent revisions may be available, but if so I have not found them. This article is based on the 2017 version.

Valence and Hydrogen Count

The central concept in the molfile format's use of hydrogen suppression is valence. The Guide defines valence in this way:

The valence property of an atom is the number of covalent bonds that can attach. If you draw a structure with fewer non-hydrogen attachments than the valence, hydrogens are assumed to be present at unfilled valences. These are implicit hydrogens. An implicit hydrogen is a hydrogen that is either assumed to be present (invisible) or attached to an atom by an invisible bond. An explicit hydrogen is a hydrogen that is attached to an atom by a visible bond.

We hit a problem right out of the gate. Consider a carbon atom in an ethene molecule whose hydrogens have been suppressed. Now try to assign a hydrogen count. Carbon has a valence of 4 because it can form four covalent bonds. Ethene as drawn has one "non-hydrogen attachment" (the carbon to which it's bonded). The number of "implicit" hydrogens equals the difference between these two values, or three (4 - 1). This answer is clearly incorrect.

We can salvage the situation through the introduction of bonding electron count. This computed value is the sum of bond orders at a given atom in a molecular graph. To obtain the hydrogen count for an atom, subtract the bonding electron count from the valence of the free atom. Viewed from this perspective, becomes equivalent to the maximum number of electrons that can be used for bonding. The relationship between hydrogen count (), valence (), and bonding electron count () is expressed quantitatively as:

Equipped with this refinement, let's return to the ethane example. A free carbon atom has a valence of four. A carbon terminal in ethene has two bonding electrons, both due to the one attached double bond. Therefore, the number of virtual hydrogens is two (4 - 2). This is the correct answer.

Computing the hydrogen count for an atom requires knowing the valence of the free atom. In other words, we need to know the number of electrons available for bonding. For atoms like carbon, this value is obvious. But for atoms like sulfur, the atomic valence is less clear. The molfile format supports two complementary approaches: default valence and custom valence.

Default Valence

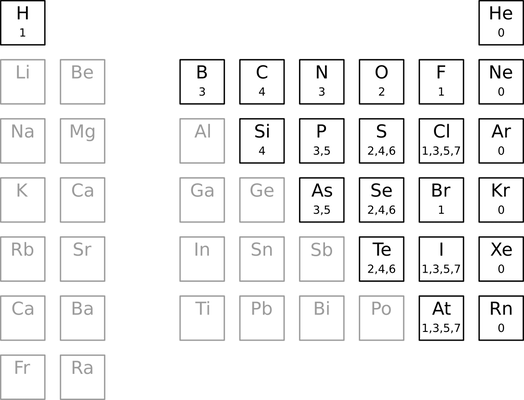

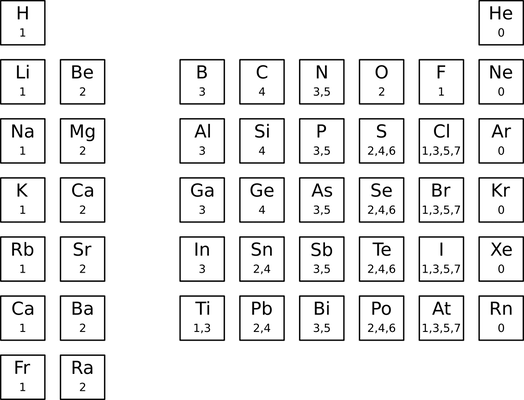

The Guide treats a handful of common atoms specially by assigning default valences. These valences are never encoded within a molfile, but instead appears in an external table.

The table defines one or more default valences over a subset of the periodic table. For example, the only default valence for carbon is 4. Phosphorous, on the other hand, supports two default valences (3 and 5). The default valences for lithium, aluminum, tin, and most metals, in contrast, are undefined. In other words, we can use the table to find the number of electrons available for bonding in select elements.

A charged atom uses the default valence of its isoelectronic analog. For example, a +1 nitrogen has a default valence of 4 (isoelectronic with carbon), whereas a -1 nitrogen has a default valence of 2 (isoelectronic with oxygen). A +1 carbon has a default valence of 3 (isoelectronic with boron). And so on. If an isoelectronic shift passes through or ends on an element with undefined default valence, then the default valence for that charged atom is undefined.

Aluminum bearing a -1 charge get special treatment. Its default valence is defined as 4.

The hydrogen count for an atom without a default valence is by default 0. For example, an unbound, uncharged lithium atom would be assigned zero hydrogens by default. The same applies to aluminum, calcium, and so on. This behavior can not be overridden with charges, except for aluminum as described above.

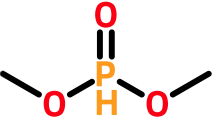

Some atoms (e.g., phosphorous, chlorine, sulfur, and selenium) support multiple default valences. In these cases, the first one greater than or equal to the bonding electron count is used. For example, the phosphorous atom in dimethyl phosphite has four bonding electrons (two from two single bonds and two from a double bond). To determine a hydrogen count, we reject the first default valence (3) because it is less than the computed bonding electron count (4). Instead, we use the next default valence (5), yielding a hydrogen count of one (5 - 4).

Sweeping changes to the default valence table were made in 2014. This event has been dubbed "MDL valence-mageddon" because of its wide-ranging, confusing, and backward-incompatible effects. As reported by John Mayfield, the pre-2014 default valence table had the following entries:

The main changes adopted after 2014 are:

- the removal of most metals;

- the removal of the 5 valence from nitrogen; and

- the removal of the 3, 5, and 7 valences from bromine.

The presence of two default valence tables raises the thorny problem of which one to use. On the one hand, the pre-2014 table has more entries and seems more complete. On the other hand, the post-2014 table is the only one currently available from BIOVIA. At the very least, documentation for software supporting the V2000 molfile format should state which valence table is being used. Hydrogen count errors in molfiles containing metals should first rule out the possibility of MDL valence-mageddon.

Custom Valence

Default valences can be overridden with a custom valence. A custom valence is an integer property encoded on a per-atom basis within the molfile atom block. This value is denoted as vvv in the CTfile formats document.

The legal values of the valence property are:

- 0: default valence

- 1-14: a literal custom valence

- 15: a custom valence of zero

For example, custom valences allow us to distinguish tin oxidation states (II) and (IV). The tin atom line for tin (II) chloride in a hydrogen-suppressed representation would be:

0.0000 0.0000 0.0000 Sn 0 0 0 0 0 2 0 0 0 0 0 0

and the tin atom line for tin (IV) chloride in a hydrogen-suppressed representation would be:

0.0000 0.0000 0.0000 Sn 0 0 0 0 0 4 0 0 0 0 0 0

An alternative approach would be to encode hydrogens atomically using full-fledged nodes and edges in the molecular graph. The availability of custom valence lets us make such decisions on a case-by-case basis.

A molfile that set the valence property of every atom would bypass the default valence table. This could offer a way out of MDL valence-mageddon.

Although the molfile format does not directly support a hydrogen count field, it does what amounts to the same thing through the valence property. As such, we can say that the molfile format supports both implicit and virtual modes of hydrogen suppression.

Radicals

The presence of a radical center at an atom reduces its hydrogen count. The molfile format supports three kinds of radicals: singlet (two electrons); doublet(one electron); and triplet (two electrons). The electron count of the radical center must be considered when computing hydrogen count. Mathematically, the relationship between hydrogen count (), valence (), bonding electron count (), and radical electron count () is:

Support

Support for default and custom valences varies across the available cheminformatics toolkits. ChemWriter is an example of a software package that supports molfile hydrogen suppression in the virtual and implicit senses. A future article will have more to say about hydrogen suppression across cheminformatics toolkits.

Conclusion

The assignment of hydrogen counts to hydrogen-suppressed molecules is an important and error-prone step when reading or writing molfiles. Contrary to first appearances, the molfile format imposes very specific rules in this regard. The error-free exchange of chemical structure information requires that all of these rules be followed.