A Minimal Molecule API

Application Programming Interfaces (APIs) are borne of conflicting demands. On the one hand, clients want an API with a lot of features. On the other hand, too many features can lead to bloat and its malevolent cousins: poor performance; brittleness; and steep learning curves. Good APIs strive for the middle ground, offering just enough functionality to solve important problems, while leaving niche features to extensions.

With the goal of seeking compromise between functionality and bloat, this article proposes a minimal Molecule API that should be applicable to many problem domains. Whether you're using a cheminformatics toolkit or building one from scratch, there's plenty here to consider.

The Irreducible Molecule

The most important API in any cheminformatics toolkit is the one describing the Molecule entity. In modern toolkits, Molecule will be an interface. In older toolkits, it may be a concrete class. A file format such as molfile defines Molecule as a flat data structure. Regardless of its particular expression, the strengths and limitations of a molecular API will be amplified many times over by the software using it. As such, it's critical to define Molecule with care from the start.

Molecule embodies the chemical concept of a molecule at some level of resolution. That last part, "some level of resolution," raises the awkward question of how far to take the abstraction. The answer depends in large part on the ways in which the software surrounding Molecule will be used. A quantum chemistry package will require very different features from Molecule than a chemical structure editor. Chemistry is a vast topic, meaning that there are almost as many ways of thinking about a molecule as there are chemists.

One solution is to use a domain-specific Molecule API — one that captures every detail relevant to a niche area of chemistry. The main disadvantage is that the team adopting such an approach must find efficient, robust solutions to a dizzying array of problems in chemistry and graph theory. Some of them are highlighted among this blog's articles. The approach can work, but it can also become surprisingly expensive. Alarmingly, the expenses can rack up at an exponential rate as project deadlines fall by the wayside.

Alternatively, a team can adopt the more practical approach of using a toolkit built around a general-purpose Molecule API. Clearly, toolkit authors can't predict every possible use of their software. They therefore must pack enough utility into Molecule to make it useful within a broad range of applications. At the same time, they must resist the temptation to cater to any particular user base to avoid bloat.

Is there a happy middle ground here, and if so, what does it look like?

Goals

Before presenting the Molecule API itself, a few words about goals are in order. There are four:

- Easy to learn. Brevity and consistency working together can go a long way toward flattening learning curves.

- Easy to use. Everything possible in other toolkits should be possible directly or indirectly.

- Simple to implement. Lowering the barrier to re-implementing

Moleculemakes several specialized performance optimizations feasible. - Simple to extend. The exact applications in which

Moleculewill be used are unknown. Therefore,Moleculemust avoid exposing functionality that will conflict with future extensions.

Molecule

For years, my company's chemical structure editor ChemWriter was built around a domain-specific Molecule API by necessity. Back in 2009 when work started, there were no JavaScript cheminformatics toolkits. Even today, the software in that category is limited.

Over years of constant use, the outlines of a cheminformatics toolkit began to emerge from ChemWriter. At its center was a minimal Molecule API. Like the minimal graph API described here recently, the minimal Molecule API is built around a handful of read-only methods. They are:

element. Returns theElementassociated with an atom given its integer ID.Elementprovides methods to query atomic number, symbol, and other attributes.isocomp. Returns anIsocomp("isotopic composition") object associated with an atom given its integer ID.Isocomprepresents the state of an atom's nucleus. At a minimum, it reports whether the composition is naturally occurring and iterates the set of mass numbers.electrons. Returns the number of nonbonding electrons associated with an atom given its integer ID.hydrogens. Returns the number of virtual hydrogens associated with an atom given its integer ID.charge. Returns the formal charge of a member atom identified by integer id.atomParity. Returns the parity of an atom identify by integer id. Atom parity, encoded as a three-member enumeration, expresses the tetrahedral arrangement of substituents as clockwise, counterclockwise, or undefined.bondOrder. Returns the formal bond order between two atoms identified by their integer ids.bondParity. Returns the parity of a bond between two atoms identified by integer ids. Bond parity, encoded as a three-member enumeration, expresses the conformation about a double bond as syn, anti, or undefined.

Atom and Bond Parity

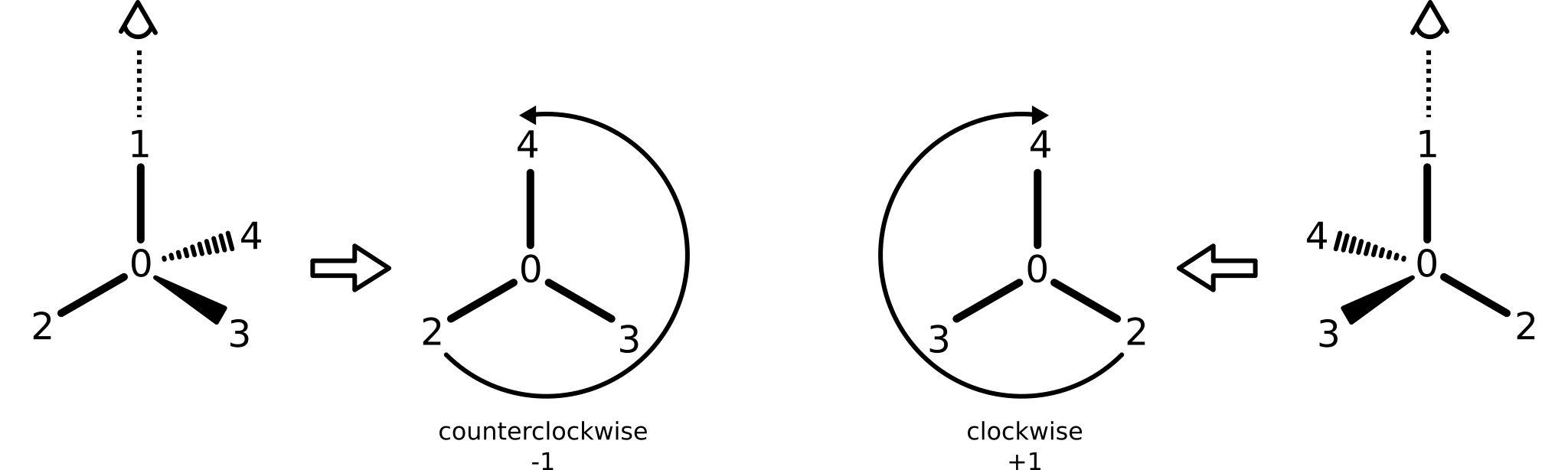

Tetrahedral stereochemical configuration is supported through the concept of atom parity, as defined by the atomParity method. This idea borrows from notions of atom parity present in both SMILES and the molfile format. View the axis defined by the bond from the neighbor with the smallest ID to a central atom. If the remaining neighbors, ordered by ascending ID, sweep clockwise, atom parity is positive (e.g., return value "+1"). Otherwise, atom parity is negative (e.g., return value "-1"). Atoms without parity assignments return a null value (e.g., "0").

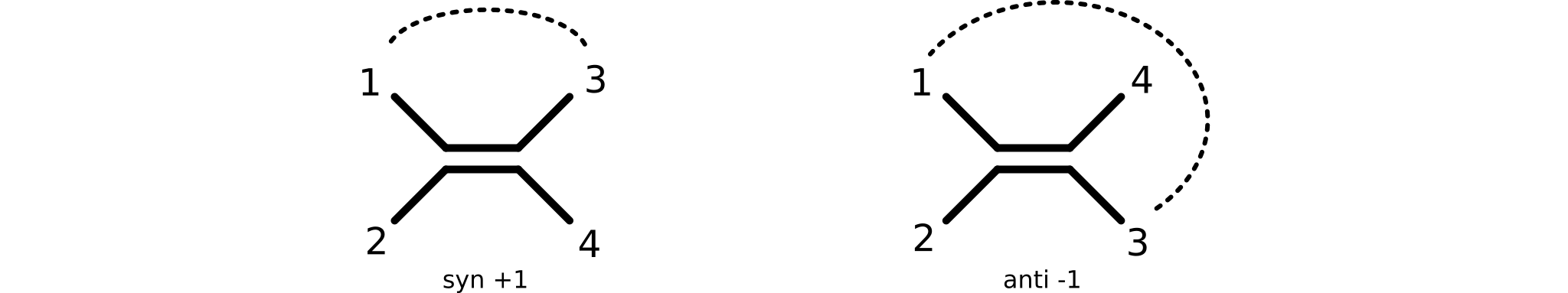

E/Z double bond conformations are supported through the bond parity concept, as defined by the bondParity method. Identify the two neighbors of the double bond system having the lowest-valued IDs. If these neighbors appear on the same side of the double bond, parity is syn (e.g., "+1"), otherwise atom parity is anti (e.g., "-1"). A double bond without parity assignment returns a null value (e.g., "0").

Atom and bond parities involving atoms bearing one virtual hydrogen can be computed by assigning it the lowest atom ID. In the case of atom parity, the axis defined by the virtual hydrogen and the central atom would be sighted. In the case of bond parity, hydrogen could be assigned the role of lowest-numbered neighbor ID.

Should an atom or bond not fit the template, the corresponding parity must be returned as null (e.g., "0"). Non-template descriptions of atomic configuration or bond conformation can be realized via Rich Expression Constructs as described below.

Both atom and bond parity rely on stable atomic IDs. After an atom is assigned an ID, it can never change in a way that affects relative ordering to neighbors. Fortunately, this constraint is easy to achieve.

Atom IDs

It may be surprising to find neither Atom nor Bond in the API description. These constructs turn out to be completely unnecessary. Unlike many toolkits, the Molecule interface described here is a single source of truth. Everything that can be learned about a molecule flows through the Molecule interface, and only that interface.

Under this system, the role of the atom shrivels to that of a mere identifier. Having lost its importance as a repository of atomic state, the need for a custom atom type itself fades away. What remains is only the requirement for unique identification of the atoms in a Molecule. This need can be filled by any built-in type. Contiguous integers in the range of 0 through one less than the order of the graph (atom count) offer a convenient and versatile option.

Similarly, the bond methods bondOrder and bondParity accept a pair of atom IDs representing the terminals of a bond. These can be supplied in either order because a Molecule also behaves as an undirected graph.

Atomic IDs are fixed on creation. In other words, atomic IDs must never change after assignment. Internally, this constraint is crucial for atomic configuration and bond conformation to remain stable. Externally, the constraint ensures that clients can store atomic IDs without them becoming invalid.

Immutability

The Molecule interface exposes no mutators. It may come as a surprise, but few situations actually require a mutable Molecule. Most application will work just fine with atomic build, extend, or read functions. Stepwise construction can be supported via methods exposed on concrete Molecule implementations.

Advantages of adopting an immutable Molecule interface include:

- simplification of the API;

- elimination of defensive copying;

- simplified use in systems languages like Rust, C++, and C; and

- simplified use in concurrent environments.

Molecule Extends Graph

In addition to its chemistry-specific methods, Molecule supports all of the methods of the minimal Graph API recently presented here. In other words, Molecule is a Graph. As such, Molecule can be used by any function or method requiring a Graph. Cycle perception, isomorphism detection, matching, traversal, and a host of complex graph operations can all be performed with equal ease on either Graph or Molecule.

Molecule in JavaScript

To make things less abstract, here's one approach to the Molecule API proposal written in modern JavaScript (specifically, ES6):

// minimal Graph API

import Graph from '../graph/graph.js';

/**

* @interface

*/

const Element = class {

/**

* @return {string}

*/

symbol () { }

// ...

};

/**

* @interface

*/

const Isocomp = class {

/**

* @return {boolean}

*/

natural () { return true; }

/**

* @return {Iterable<number>}

*/

isotopes () { return undefined; }

};

/**

* @interface

*/

const Molecule = class extends Graph {

/**

* Returns the element of the atom identified by id.

*

* @param {number} id

* @return {Element}

* @throws {Error} given invalid id

*/

element (id) { return undefined; }

/**

* Returns the isotopic composition of the atom identified by id.

*

* @param {number} id

* @return {Isocomp}

* @throws {Error} given invalid id

*/

isocomp (id) { return undefined }

/**

* Returns the valence electron count of the atom identified by id.

*

* @param {number} id

* @returns {number} an integer greater than or equal to zero

* @throws {Error} given invalid id

*/

electrons (id) { return 0; }

/**

* Returns the virtual hydrogen count of the atom identified by id.

*

* @param {number} id

* @returns {number} an integer greater than or equal to zero

* @throws {Error} given invalid id

*/

hydrogens (id) { return 0; }

/**

* Returns the formal charge of the atom identified by id.

*

* @param {number} id

* @return {number} may be a non-integer

* @throws {Error} given invalid id

*/

charge (id) { return 0; }

/**

* Returns a number representing atom parity.

*

* To determine atom parity, sight down the axis from the lowest-indexed

* neighbor of atom to the atom. If the remaining neighbors are arranged

* clockwise in order of index, parity is +1. Otherwise, parity is -1.

*

* If no parity is assigned, 0 is returned.

*

* @param {number} id

* @return {number} -1 (anti), 0 (none), 1 (syn)

* @throws {Error} given invalid sid or tid

*/

atomParity (id) { return 0; }

/**

* Returns the formal bond order between atoms identified by sid and tid.

*

* @param {number} sid

* @param {number} tid

* @return {number}

* @throws {Error} given invalid sid or tid

*/

bondOrder (sid, tid) { return 0; }

/**

* Returns a number representing the bond parity.

*

* If positive, the two lowest-indexed atoms on either terminal are syn. If

* negative, the lowest-indexed atom on one terminal is anti to the

* lowest-indexed atom on the mating terminal.

*

* @param {number} sid

* @param {number} tid

* @return {number} -1 (anti), 0 (none), 1 (syn)

* @throws {Error} given invalid sid or tid

*/

bondParity (sid, tid) { return 0; }

};

export { Molecule, Element, Isocomp }

Extension via Rich Expression Constructs

It may seem as if the Molecule interface precludes advanced forms of molecular representation such as multi-atom bonding and non-template stereochemistry. On the contrary, the approach outlined here supports them by not interfering with them.

Consider, for example, the bondOrder method which returns a floating point value. Toolkits lacking multi-atom bonding support can implement bondOrder by returning an integer. This yields a fast implementation unburdened by overhead from unused features.

What if a toolkit requires multi-atom bonding? In such cases, Molecule can be extended with the following functions:

bondingSystems. Iterates all Bonding Systems in theMolecule. A bonding system is a subgraph with an electron count attribute as recently described.bondingSystemsAtAtom. Iterates all bonding systems containing the member atom identified by ID.bondingSystemsAtEdge. Iterates all bonding systems containing the edge specified by two atom IDs.

Notice that the presence of these methods in no way interferes with the presence of the the original bondOrder method. They can both be present without causing conflict. Moreover, it's possible to implement the bondOrder method through analysis of the bonding systems in a molecule.

Likewise, non-template stereochemical configuration and conformation can be supported without conflicting with the atomParity or bondParity methods. Should such advanced capability be required, Molecule can be extended to support two additional functions:

configuration. Returns the configuration (which may be undefined) of the atom identified by its ID. The result is a "paddle wheel."conformation. Returns the conformation (which may be undefined) for a molecular path defined by a sequence of atom IDs. As withconfiguration, the result is a "paddle wheel."

I'll have more to say about configurational and conformational paddle wheels in a later post. As with bondOrder, both bondParity and atomParity can be computed from internal representations that also support configuration and conformation.

Specialized Extensions

Molecule as described here lacks a lot of functionality that might seem essential. For example, how can graphical applications use a Molecule that lacks even the most rudimentary support for atomic coordinates?

In the specific case of 2D graphics, the answer is simple. We define a distinct construct encapsulating the behavior of a 2D coordinate plane. In other words, we define a Plane interface.

Plane would provide methods for writing, reading, and transforming a set of points referenced by atomic IDs. If a function or method requires 2D atomic coordinates, we can pass an object implementing Plane, and possibly a Molecule as well.

For 3D graphics applications, replace Plane with a Space interface.

This approach can be extended to capture and use a wide range of specialized information about atoms, bonds, and molecules. At no time does it become necessary to force these capabilities onto Molecule itself.

Conclusion

Molecule is a minimal interface for objects and data structures possessing molecule-like behavior. With only a handful of methods to worry about, toolkits based on Molecule are easy to learn and use. Exposing only a core of irreducible methods enables conflict-free extensions, application-specific enhancements, and many performance optimizations.