Opting out of Optune

In March 2023 I was diagnosed with a form of terminal brain cancer called "glioblastoma." The surgery to extract the tumor from my brain was considered unusually successful. Unfortunately, surgical success won't change the fact that I'll die from glioblastoma sooner rather than later. And it's like this for thousands of patients in the US every year. It doesn't matter how famous or powerful you are. Senators John McCain and Ted Kennedy, and Joe Biden's son are all thought to have died from glioblastoma. You can throw all the money you want at glioblastoma, assemble the best surgeons and experts from around the globe, and it won't change the outcome. Fight, pray, hope, spend, and fulminate all you want, glioblastoma takes no prisoners.

Given the appalling state of interventions, you'd think the entire field of neuro-oncology had been sitting on its collective hands for the last four decades. Untold millions of dollars and tens of thousands of dead patients have barely budged the prognosis, which is still measured in months.

My glioblastoma appears to have been unusually invasive because soon after surgery my symptoms worsened while my MRI revealed hints of tumor growth. This worsening continued right through chemoradiotherapy. During this time both heads of my medical team, Drs. Neuro-Oncologist and Radiation Oncologist, ascribed my worsening condition to treatment effects. In other words, the poisonous drug I was taking and the lifetime maximum dose of high-energy X-radiation shot into my brain were doing their job. I had doubts.

This madding game of blame-the-bad-things-on-treatment eventually ran its course. By August 2023, I was beyond the window of time that treatment effects could be the cause. My symptoms grew more noticeable by the day, and my latest MRI looked worse than the last. Dr. Neuro-Oncologist told me what I'd sensed for months: the tumor had shrugged off the best that modern medicine could muster. The standard of care treatment had failed.

What remained were treatments outside the standard of care, which Dr. Neuro-Oncologist laid out for me:

- Lomustine. This is another systemic alkylating agent, meaning that it works like the one I'd already taken and which had proven ineffective. Lomustine also had a similarly serious range of side-effects. Dr. Neuro-oncologist insisted that Lomustine could work on patients like me, but I found no evidence for this in the medical literature. Lomustine got two thumbs down.

- Avastin. Also known as Bevacizumab, I won't dwell on this problematic drug other than to say that my reading of the literature says that Avastin is more effective at treating MRIs than glioblastoma. It's palliative at best, and I had no interest in that.

- Clinical Trials. It's not like smart, hard-working people aren't trying to come up with effective treatments or even cures for glioblastoma. It's that the problem is so difficult. At any given time there are a dozen or so ongoing clinical trials in the US alone. But a review of what would be available to me was underwhelming. I was determined to avoid the medicalization of my last days on earth, so any experimental treatment I'd submit myself to would need to justify itself in creativity, innovation, and likelihood of success. Nothing came even close to meeting that standard. I would not be enrolling in clinical trials.

- Optune. The remainder of this article will describe this treatment and explain why I declined it.

Optune is a medical device consisting of a battery pack/control unit tethered by a wiring harness to transducer array attachment worn on the head. The manufacturer recommends wearing the attachment for at least 18 hours a day. The attachment directs alternating electromagnetic fields into the brain of the wearer. Additionally, the wearer takes the standard of care chemotherapeutic temozolomide. This is the same drug found to show little to no efficacy in patients with genetic markers like mine, but I'm getting ahead of myself.

The US FDA approved Optune for the the treatment of recurrent glioblastoma in 2011. But this was not straightforward. The letter from the FDA made additional stipulations, the strongest of which was to conduct a "post-approval" study aimed at demonstrating that the device was "non-inferior" to the standard of care ("chemotherapy," presumably temozolomide). Moreover, the approval proceedings themselves were reportedly noteworthy:

… the considerable presence of glioblastoma patients in the hearing room, not to mention their pleas during the open public hearing, helped nudge along opinions among panel members. Despite huge misgivings on several points, the panel voted 7-3 (with a pair of abstentions) that the benefits of the device outweighed the risk.

The emotional attachment to the device makes Optune unusual among glioblastoma treatments - even today. You just don't find people emoting in favor of, say, radiotherapy or temozolomide in the way they do about Optune. I can only imagine what the atmosphere in that hearing room was like. The FDA would later approve Optune for the treatment of newly-diagnosed glioblastoma in 2015.

Early work on what would become Optune was reported in 2007. A team from NovoCure, Limited, the company that would develop and market Optune, studied disruption to cell mitosis caused by alternating electric fields. DNA carries charge. As such, its orientation and position can be controlled by electrical fields, as seen in for example electrophoresis. Alternating electric fields were found to disrupt cell division, especially in rapidly-dividing cells such as those found in tumors. The effect was seen in vitro, in animal models, and in humans.

Relevant clinical work on Optune can be found in the following papers:

- NovoTTF-100A versus physician’s choice chemotherapy in recurrent glioblastoma: a randomised phase III trial of a novel treatment modality. This study, also known as "EF-11," was published in 2012. All patients were required to have "recurrent" tumors, meaning tumors that had grown back after surgery. The control group was administered the "best available" chemotherapy. The study group was administered Tumor Treating Field (TTF) "monotherapy," meaning no other treatment such as temozolomide was allowed. Median survival was 6.6 months compared with 6.0 months for the control group.

- Effect of Tumor-Treating Fields Plus Maintenance Temozolomide vs Maintenance Temozolomide Alone on Survival in Patients With Glioblastoma: A Randomized Clinical Trial. This study, also known as "EF-14," was published in 2017. Patients whose tumors returned within three months after surgery ("early progression") were excluded. The control group was given temozolomide and the study group was given temozolomide simultaneously with TTF. Median survival was 20.9 months in the study group compared with 16.0 months for the control group.

- Increased compliance with tumor treating fields therapy is prognostic for improved survival in the treatment of glioblastoma: a subgroup analysis of the EF-14 phase III trial. This study re-evaluates the data from EF-14 to measure the relationship between TTF "compliance" and benefit. A positive correlation between compliance and median survival was found.

My main interest in these studies was to answer a question relevant to my own case: what can an MGMT unmethylated patient reasonably expect from Optune? A secondary question was: what can a patient with early recurrence reasonably expect from Optune?

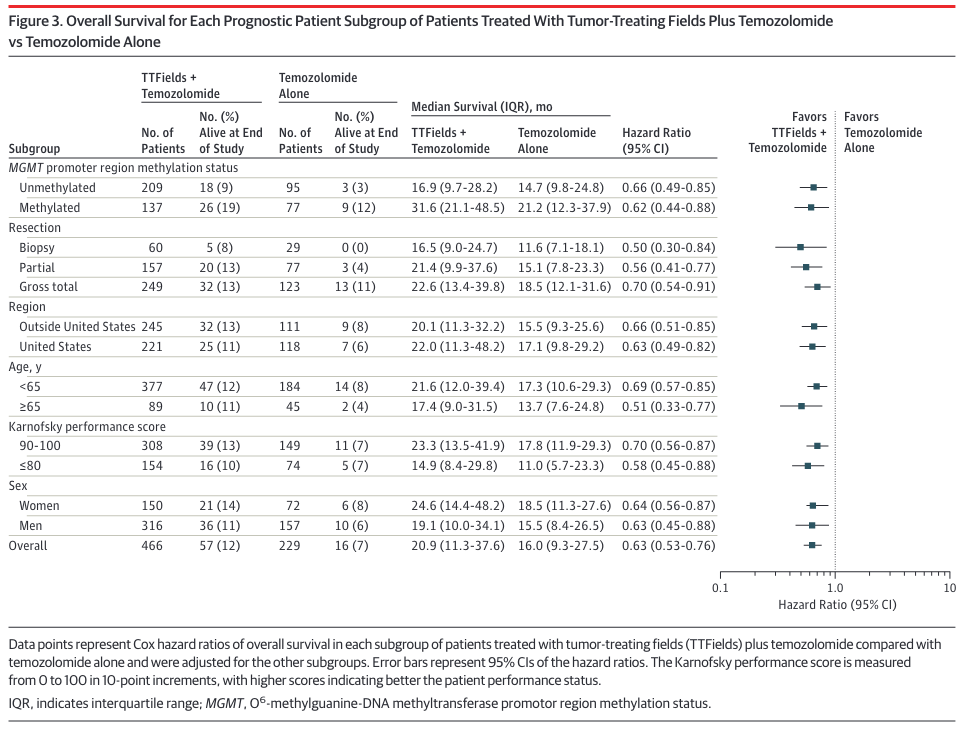

EF-14 breaks down the response to TTF + TMZ based on several factors, including MGMT methylation status:

As seen in the table's first two rows, unmethylated patients (median survival 16.9 months) fare much worse with Optune than those with methylated MGMT promotors (median survival 31.6 months). Both groups were administered temozolomide, but as noted earlier this drug has been known for years to offer little to no benefit to the aproximately half of glioblastoma patients with unmethylated MGMT promotors. A study arm that might have detected synergistic action in unmethylated tumors (TTF alone vs. TTF+TMZ) does not appear to have been performed here. TTF Monotherapy was performed in EF-11, but it's not clear how to compare the results of that study with others.

These median survival times might look much longer than expected. For example, the unmethylated control group, which received only temozolomide, had a median survival of 14.7 months (first row). This doesn't fit with the standard of care clinical study which reported median survival of 12.6 months for unmethylated patients treated with temozolomide.

The difference in reported median survival for unmethylated patients stems from two differences in the EF-14 study. First, median survival in EF-14 was reported relative to randomization, not diagnosis. Randomization occurred roughly 3.8 months after diagnosis. But this makes the median survival time even longer than expected for the unmethylated control group (14.7 months + 3.8 months = 18.5 months). The difference reflects the much better prognosis for patients whose tumors do not recur early. EF-14 completely excluded these patients, which I presume accounts for the across-the-board longer median survival times.

All of which is to say that EF-14 shows that Optune offers MGMT unmethylated patients a survival benefit over temozolomide alone. Unfortunately, this benefit boils down to a paltry 2.2 months (16.9 months - 14.7 months, according to the first row of the table) for patients whose tumors lack MGMT promotor methylation.

For such a slim survival benefit, it's reasonable to ask tough questions about cost. Optune is not cheap (on the order of tens of thousands of dollars from what I gather). But I'm setting this part of the consideration aside to focus on what MGMT unmethylated patients must do on a daily basis to receive Optune's two-month survival benefit.

The FDA has published instructions on the use of Optune, which include:

- "You should use Optune for at least 18 hours a day to get the best response to treatment."

- "If you plan to be away from home for more than 2 hours, carry an extra battery and/or the power supply with you in case the battery you are using runs out."

- "Make sure you have at least 12 extra transducer arrays at all times."

- "The transducer arrays are for single use and should not be taken off your head and put back on again."

- "… the transducer arrays need to be replaced once to twice a week and the scalp re-shaved in order to maintain optimal contact."

Dr. Neuro-Oncologist assured me that those patients they have treated with Optune learn to live with its requirements.

Nevertheless, I was curious about that 18-hour per day requirement. For example, imagine a patient sleeps eight hours a day. That leaves at least two hours each night during which they would need to sleep while wearing a transducer array suctioned in place to the scalp. How quickly does Optune's benefit drop off with disuse?

The third study I linked attempts to answer this question. It relates a metric called "compliance" to median overall survival. Unfortunately, the term "compliance" is not concisely defined. Instead two statements are made about it. The first is:

Compliance data are derived from the internal computerized log file of each NovoTTF-100A (Optune®) device. Percent of the total treatment time during with the NovoTTF-100A treated patients actually received treatment was calculated by analyzing the log file of each device and dividing the total device 'ON' time by the prescribed number of 1 month treatment courses.

This statement is unfortunately gibberish to me. Dividing a time quantity by a count will yield a value with units of time/unit. It will not yield a percentage.

The second statement is:

Patient compliance was calculated as the average percentage of each month the system was delivering TTFields.

This is a little better in that it can in fact yield a percentage.

Putting the two statements together, I gather that "compliance" was computed as something like the amount of time the device log reported a status of 'ON' divided by the amount of time for the month in question.

This may sound like nit-picking but it's quite important. "Compliance" could mean the amount of time the device was 'ON' divided by the amount of time the device should have been 'ON'. If so, this could be a much easier bar to clear.

If the other interpretation is correct, 90% compliance means that the device is 'ON' 90% of the time available in the interval being studied. If that were one day, then 90% compliance means the device was 'ON' 21.6 h. 75% compliance would mean the device was 'ON' for 18 h.

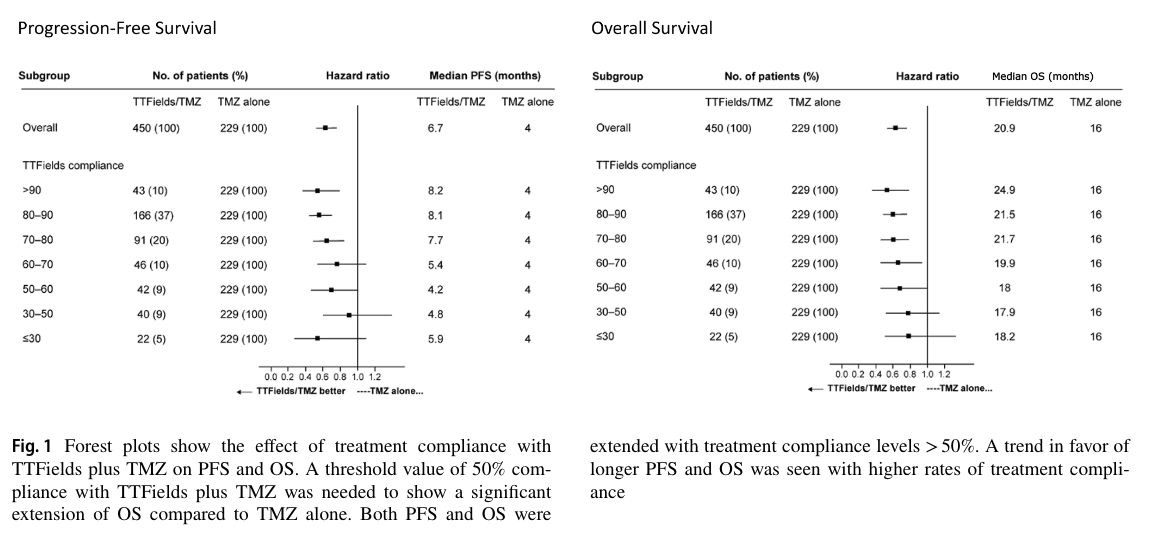

However "compliance" may have actually been measured, Figure 1 of the study relates it to what patients care a lot about — survival.

The authors note that 50% compliance (12 h per day) is the level required to see "significant extension" of overall survival. This translates into a median survival of 18 months vs. 16 months for temozolomide alone. At the recommended 75% compliance (18 h a day 'ON'), median survival was 21.5 months compared to 16 months for temozolomide alone.

As far as I can tell, this breakout of the EF-14 data did not address the relationship between compliance and median survival for MGMT unmethylated patients.

Another unanswered question relates to early recurrence. The EF-14 study excluded these patients entirely. The EF-11 study included them, but did not distinguish between early and late recurrence.

To recap, Optune offers patients with unmethylated MGMT promoters an advantage in median survival of about two months. It's likely that to receive that benefit the patient would need to take temozolomide, and wear the powered Optune attachment on a freshly-shaved scalp for a minimum of 18 h per day, effectively forever.

It's not nothing, but the costs of Optune outweigh the benefits in my opinion. My tolerance for medicalization is very low and my preference for quality vs. quantity of life skews heavily toward quality.

The options open to a glioblastoma patient all tend to involve the administration of temozolomide, with Optune being a case in point. As long as this approach to therapy remains standard practice, patients whose tumors lack MGMT methylation will continue to get the short end of the stick in both treatment and research.