The Geiger Counter

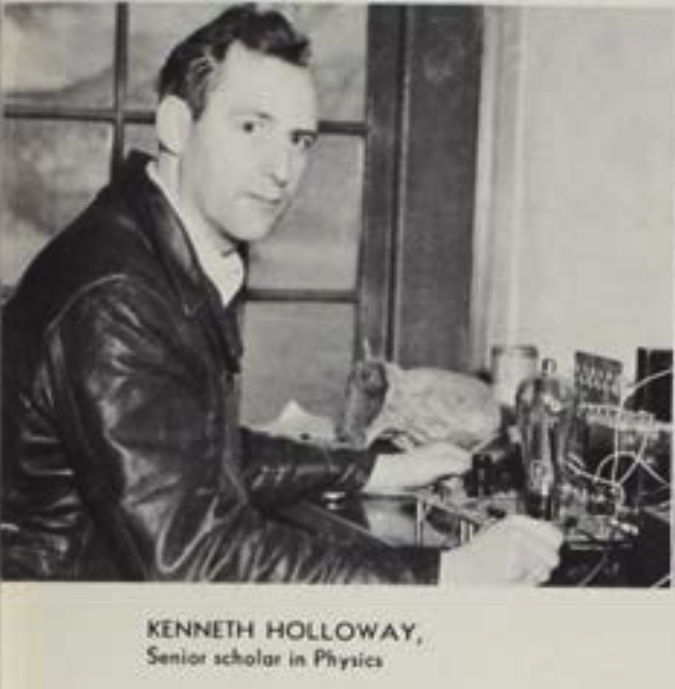

My grandfather, Kenneth O. Holloway ("Kenny"), worked as an engineering assistant at the Hanford Engineer Works ("Hanford") near Richland, Washington. He never talked about what he did there, and died at the age of 35 — long before I was born. Given just a few morsels of family history and some internet tools, I wanted to piece together the story of what what brought Kenny to Hanford and what he may have done there. I've learned a lot about Kenny's parents and his turbulent childhood. I've also learned a little about Kenny's engineering work at Boeing before World War II and his first three years of college after the war.

Spring semester of 1948 was the start of Kenny's senior year at Willamette University (WU). By this time, he was done with general requirements and moved onto advanced courses in electricity and magnetism, modern physics theory, thermodynamics, and differential equations.

In addition to these courses, Kenny was selected as a WU "Senior Scholar." This program paired seniors enrolled at WU with a member of the university faculty to tackle research problems. The 1949 WU yearbook has this to say about senior scholars:

The senior scholar is a senior student who has proved especially proficient in his particular field. His work in this field is continued further by assisting his major professor. This assistance consists of paper correction and research in the Language, Literature and Social Science departments, laboratory assistance in the Natural Science department and test grading and assistant teaching in the School of Music.

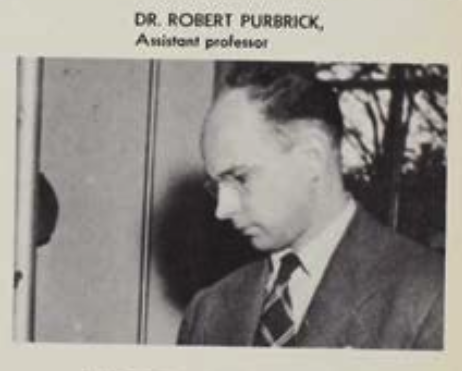

Kenny joined the laboratory of Robert L. Purbrick. Just the prior year, Purbrick himself had joined the WU physics faculty, where he promptly began a research program aimed at turning physics theory into technologies to solve practical problems. Soon after joining the faculty, Purbrick had taken delivery of two tons of WWII surplus electronics equipment, aiming to harvest and re-purpose the components.

Although his early work was focused on the atomic bomb, Purbrick had a longstanding interest in practical (and peaceful) applications of nuclear physics. While at the University of Chicago, and as part of the Manhattan Project, he worked with Enrico Fermi to build and operate the world's first nuclear reactors. Much of this work remains classified.

Fortunately, one paper co-authored by Purbrick in 1945 has been declassified. It describes a two part investigation into the radionuclide carbon-14. Most of the carbon present in our bodies and in barbecues comes in the form of carbon-12, which has six neutrons. In comparison, carbon-14 has eight neutrons, or two more. As the paper describes, this unusual form of carbon can be made from either nitrogen or carbon through bombardment with neutrons. In the work done by Purbrick, these neutrons came from the University of Chicago's CP-3 nuclear reactor ("Chicago Pile 3").

The University of Chicago team sealed samples containing either carbon or nitrogen in a cylindrical chamber, five inches in diameter and twelve inches long. Then they exposed these cylinders to the neutron flux (flow of neutrons being produced in the nuclear reactor) of CP-3. On completion of the reaction, the chambers were broken open and the contents processed and analyzed.

CP-3 differed from the production nuclear reactor built at the Hanford Site near Richland, Washington in two main ways. First, CP-3 was a research reactor and therefore only a fraction of the size of what was built at Hanford. Second, CP-3 used heavy water as a moderator, whereas Hanford's reactor used carbon (graphite). The practical differences between these two designs was one of the reasons Germany, which pursued heavy water reactors, failed to develop an atomic bomb during World War II. The difference also became a minor plot point in the 2023 movie Oppenheimer.

The second part of Purbrick's study estimated the half-life of carbon-14 obtained in the first part. This work relied on a Geiger counter to measure the decay of radionuclide over time. Even at this early point in the history of nuclear technology, practical applications for carbon-14 in biology and medicine were on the drawing board. The half-life of carbon-14 would become an important yardstick in this work, and counters of various designs would become indispensible tools.

In addition to his scientific skills, Purbrick knew how to get press coverage for his research. The Oregon Statesman of December 4, 1948, reported on the work Kenny and two other group members were doing. That work involved the design and construction of a Geiger-type detector and the electronics equipment to control and read its signals.

Commenting on his buy-versus-build thought process, Purbrick said:

We could buy the equipment outright and get it assembled much quicker, but by using materials obtained from war surplus distributors and making the outfit ourselves, we get much more experience and cut the cost to about one tenth of the ready-made machine.

The article went on to discuss some of the peaceful applications that might result from the device the group was building.

Work on counters would continue in the Purbrick lab after Kenny graduated. One goal goal was to increase the sensitivity of carbon-14 detection, harking back to Purbrick's research at the University of Chicago. An article in the Capital Journal (April 13, 1951) referenced this earlier work, noting the possible applications in medicine:

One interesting use of tracer elements has been in the determination of the way in which digitalis affects the heart when used as a medicine in the treatment of heart disease. Digitalis is extracted from the foxglove flower, which is common in Oregon. By raising the plant in an atomsphere of radioactive carbon dioxide the resulting digitalis is partially constructed of radioactive carbon. When the radioactive digitalis is introduced into the body, investigators are able to trace its path and determine how it works. …

A counter such as the one produced at Willamette should be useful in such research. Other uses may be found in cancer research, the effect of sulphur drugs, and photosynthesis in plants.

Later, Purbrick's lab would go on to publish a paper describing the design, construction, and testing of such a counter for carbon-14.

Kenny worked on at least one other project while in Purbrick's lab (Capital Journal December 2, 1948). The underlying idea was that bacteria could be killed through exposure to supersonic waves. The idea was to build a device capable of emitting these waves. Applications in food preparation and medicine were considered. Details were unfortunately scant, and there was apparently no follow-up, either in the newspaper, or the scientific literature.

Despite the valuable hands-on experience he was getting in Purbrick's lab, Kenny withdrew from his Senior Scholar appointment sometime during the Fall 1948 semester. It was his first and only "W" while at Willamette. It's hard to imagine that this withdrawal resulted from disinterest with what he was learning in the lab. A more likely reason was Kenny's personal life, which had become much more complicated by the time he graduated. Although Kenny may have dreamed of a future filled with advanced physics research and maybe even a graduate degree followed by an academic career like his mentor Dr. Purbrick, life was already pulling in other directions.