Beating Swords into Ploughshares

Whatever Kenny may have done during World War II, he returned to Salem determined to push his education as far as possible. In the Spring 1946 semester, he enrolled as an undergraduate at Willamette University (WU), majoring in mathematics and physics. Like many veterans returning from the war, Kenny took advantage of the Servicemen's Readjustment Act of 1944 ("GI Bill"). The National Archives says this about it:

Signed into law by President Franklin D. Roosevelt on June 22, 1944, this act, also known as the G.I. Bill, provided World War II veterans with funds for college education, unemployment insurance, and housing. It put higher education within the reach of millions of veterans of WWII and later military conflicts.

Uncle Sam was offering a free ride through college and Kenny jumped at the chance. He would do now what wasn't possible before the war.

The choice of mathematics and physics as major is surprising. If Elmer, Kenny's father, had any interest or particular skill in these areas, there is no record of it. Elmer's family, the Holloways of Indiana, worked the land. Likewise, the Blinstons of Rosedale were farmers and merchants, with no hint of scientific or academic leanings. In fact, no branch in Kenny's family tree offers the slightest hint of interest or aptitude in higher education, let alone scientific research.

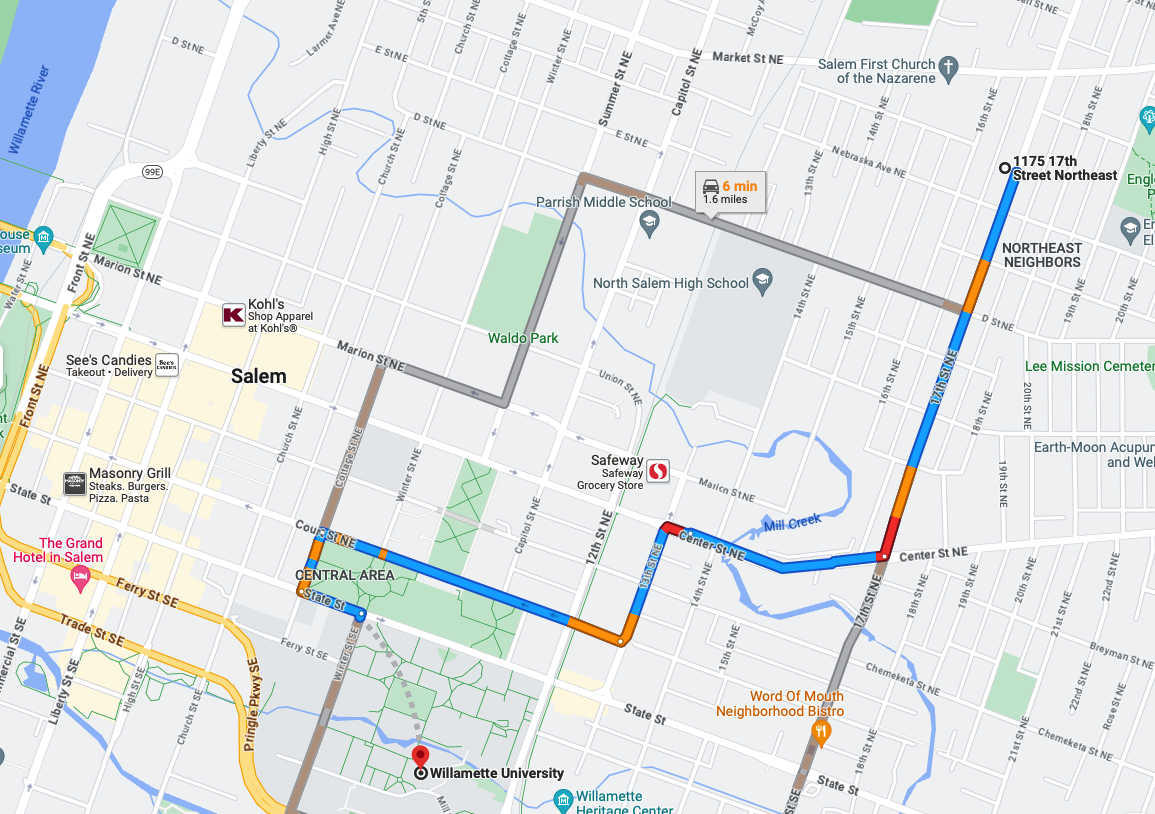

Whatever Kenny's reasons for choosing his university and major, WU was an excellent fit. Located in Salem, it was just a mile walk from where Kenny lived at 1175 N. 17th St. He shared this house with with his father, who was 64 years old. Elmer would die in 1960 from pulmonary thrombosis and other causes. It's possible that symptoms may have appeared by the time Kenny enrolled at WU. If Elmer needed anything, Kenny would be able to help.

WU has a long and complex history. According to the university's history page, WU traces its origins to a Methodist mission school in 1834 and the Indian Manual Labor Training School in 1841. Over the next few decades, WU would found the first medical and law school in the Pacific Northwest. Over time the university would sell off most of its land holdings. These sold parcels would congeal to form the current downtown Salem area. Wikipedia describes WU as "the oldest college in the Western United States."

More than convenience, historic tradition, and an unbeatable price, WU offered a full selection of courses needed to finish a math and physics major. In his first semester (Spring 1946), Kenny completed general physics, mathematical analysis, and engineering drawing. During the Summer 1946 session, he took the second part of general physics, and physical descriptive geometry. According to the 1945-1946 Course Catalog (obtained through the helpful staff at WU Archives), the two general physics courses were required prerequisites for majors.

The 1946 WU yearbook (Wallulah 1946) doesn't include Kenny's picture or name. This isn't surprising because only the students in the senior class had pictures and listings. Other individual pictures were reserved for members of fraternities, which Kenny apparently didn't belong to.

In his sophomore year (1946/1947), Kenny studied mathematical analysis, general chemistry, calculus, mechanics (Part I of the college physics curriculum), and optics (Part II of the college physics curriculum).

The coursework in Kenny's junior year (1947/1948) included chemistry (qualitative analysis), electrical measurement, advanced calculus, modern physics, and electronics. Although Kenny passed his chemistry class, he did so barely — with a D. Clearly, this topic held little interest for him. Kenny also took an elementary German class.

A physics major taking a German class might seem odd. However, German was an essential language of science until World War II. A lot of the scientific literature, old and contemporary, was written in German, and so the ability to at least understand the language would be useful to any scientist, and especially a physicist. The Course Catalog had this advice for Physics majors:

Students who plan to do graduate work in Physics [e.g., PhD] should arrange their major to include Mathematics 55, 56, 57, and 58, also Chemistry 65, 66 [Physical Chemistry]. The foreign language, for this latter group, should be either French or German.

Although it wasn't required for the bachelor's degree, Kenny appeared to be planning ahead for graduate studies by taking German. It was one of two languages recommended by the physics department for this purpose. The fact that Kenny never took physical chemistry, a class considered difficult even by chemistry majors, suggests his graduate studies plan may have have been preliminary.

WU was a good fit for another reason: professor Robert L. Purbrick (Purbrick). Purbrick was the dynamic force behind the growth of the WU physics department during the 1950s and 1960s. Kenny worked with Purbrick on scientific research projects outside of the required academic classes.

Purbrick's most notable scientific accomplishment was his work for the Manhattan Project, as described in his obituary (The Statesman Journal October 8, 2010). Together with Enrico Fermi, who would go on to win the Nobel Prize, Purbrick helped construct and operate the world's first two nuclear reactors at the University of Chicago. Much of the work Purbrick did during World War II was classified. Along with 70 other scientists, Purbrick signed the petition led by Leo Szlilard urging President Truman to avoid using the newly-developed atomic bomb on Japan:

The war has to be brought speedily to a successful conclusion and attacks by atomic bombs may very well be an effective method of warfare. We feel, however, that such attacks on Japan could not be justified, at least not until the terms which will be imposed after the war on Japan were made public in detail and Japan were given an opportunity to surrender.

As Kenny started his junior year in 1947, Purbrick became a professor of physics at WU. In a stroke of luck and imagination, shortly thereafter Purbrick took delivery of two tons (50 crates) of surplus military electronics equipment, valued originally at roughly $100,000 (pre-inflation , Statesman Journal January 25, 1948). Included in the haul were large cathode ray tubes, about 3,000 radio tubes, electrical meters, batteries, telephones, and various types of radios. Purbrick planned to use the equipment to build custom devices as part of his research program.

Purbrick's research combined advanced physics theory with practical applications. Some of the devices designed and built in Purbrick's group had clear uses in health and medicine. It was an ideal environment to develop skills and ideas that would serve Kenny well at Hanford.