Growing Pains

The loss of a parent, especially in childhood, is one of the most traumatic events a person can experience. Not only do children face the loss itself and all of its emotional and material consequences, but the surviving parent must deal with their own grief while trying to raise children. It's not surprising that all of the research on this topic points to challenges well into adulthood for surviving children. For the lucky ones, family, friends, and skilled professionals can step in to soften the blow.

In the spring of 1923 this ordeal hit Kenny and Dorothy Holloway, but luck was not on their side. Their mother, Eva Loretta Holloway, had just died of tuberculosis. The children's father, Elmer Holloway had no blood relatives in the area. An uncle lived with his wife in Washington state, but the rest of the Holloway clan was clustered in Indiana.

Nor does it seem likely that Elmer could rely on his wife's family, the Blinstons. Although they lived in Rosedale, not far from Salem, the unusual circumstances around Elmer's marriage may have estranged him from the family.

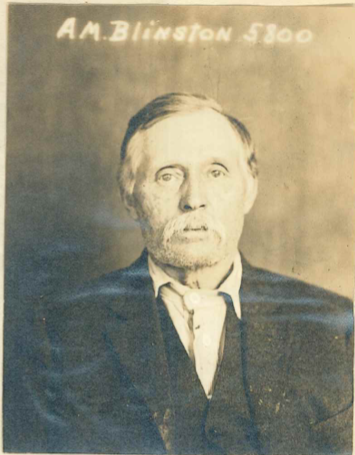

To make matters worse, the Blinstons had problems of their own. A guardian for the person and estate of patriarch Albert M. Blinston ("Albert") was appointed in 1919 (Statesman Journal July 2, 1919). Albert had been found insane and incapable of managing his own affairs.

On January 3, 1923, two of the Blinston children, "M. Blinston" and Clara Blinston, successfully petitioned Marion County (where Salem is located) to commit their father. According to the petition, a copy of which I obtained, Albert threatened family members and "drew an axe on his son in law." The petition alleges that Albert was "gradually becoming demented, for the past 4 years." The timing of the petition suggests that this axe incident may have occurred around the Christmas holiday of 1922.

On April 28, 1923 Albert Blinston was committed to Oregon State Hospital (OSH) in Salem. Also known as the "insane asylum," OSH was a well-known institution in Oregon and even across the US. The 1975 Oscar-winning movie One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest was filmed at OSH.

In 1924 a probate court would rule on a case involving the Blinston estate (The Oregon Statesman February 2, 1924, page 5). Two wills were reportedly made, the second allegedly after Albert had been declared insane. At stake was an estate consisting of "personal property to the value of $100,000 [nearly $2M today] and real property to the value of $12,500 [over $200,000 today] and with a rental value of $600 [about $10,000 today] annually." The court was asked to decide which of two wills was valid. The verdict was not recorded publicly, but I have requested the court record from the county.

The case of the Blinston estate would drag on for many years — throughout Dorothy and Kenny's childhood and beyond. In 1937 a guardian ad litem for the children was appointed, John F. Steelhammer (Statesman Journal May 13, 1937). This was not a guardian in the sense of caring for the children, but rather representing their legal interests. Cornell School of Law) explains the duties of a guardian ad litem as follows:

A guardian ad litem (GAL) is a person appointed by a court to look after and protect the interests of someone who is unable to take care of themselves, typically a minor or someone who is determined to be legally incompetent. They are appointed to a specific case, and their role is to watch over the ward and make sure their interests are protected. They are usually appointed in cases involving disputes over child custody, child support, adoption, divorce, emancipation of minors, and visitation rights. They act as factfinders for the court, making recommendations based on what is best for the ward, rather than advocating for the ward's preferences. Guardians ad litem are regulated by state and local laws, which vary in terms of qualifications, training, compensation, and duties. …

As children to the deceased Eva, who herself was heir to the Blinston estate, Kenny and Dorothy stood to inherit a lot of money. Steelhammer's job was to ensure they were treated fairly in court as the Blinston children jockeyed for their share.

With two children to care for, his family far away, his in-laws preoccupied with Albert and his estate, and a job that made it difficult or impossible for him to be home during the day, Elmer was probably desperate for help. He'd turn to someone who could not provide it and had problems of her own. On May 12, 1924, Elmer Holloway married Marion M. Gregg ("Marion") in Salem.

Marion's early life is just as obscure as Elmer's, but she apparently brought two daughters into the marriage. It seems likely that they too would have shared the Holloway house with Dorothy and Kenny. The family of three became a family of six.

Just two months later, Gregg would file for divorce, alleging "cruel and inhuman treatment" by Elmer. She asked for nothing but the restoration of her name prior to marriage and custody of her two daughters. In 1924 the divorce was finalized. Within the span of less than a year, Kenny's mother had died, he'd gained a step-mother and two step-sisters, and then lost them as quickly as they appeared.

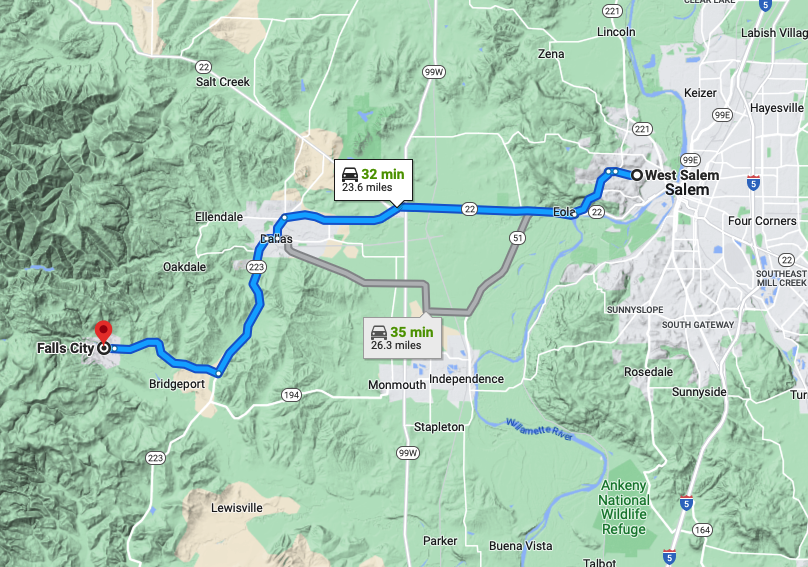

Kenny and Dorothy were in for still more changes. Sometime between 1924 and 1930, the Holloway family moved again. This time they left Salem for Falls City, Oregon.

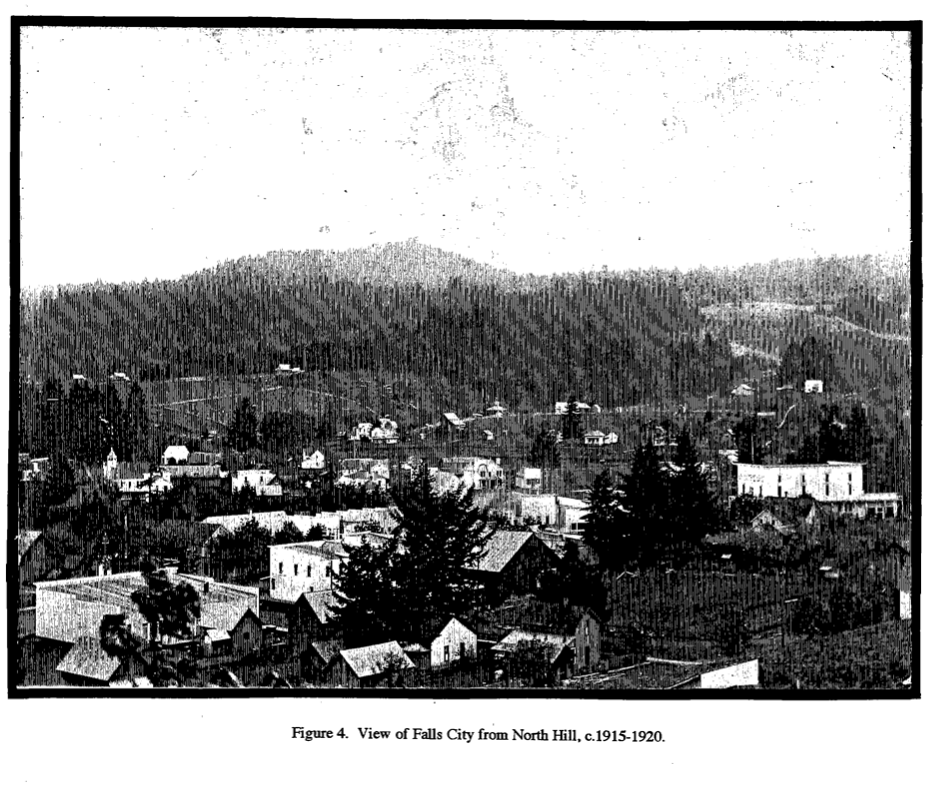

Despite its small size, Falls City takes its history seriously. In 1997 the town commissioned a historical context statement, The Development of Falls City, Oregon 1845-1965, part of a historical preservation plan. This document's rich detail offers hints as to why the Holloways may have moved to Falls City.

One factor could have been the prospect of a well-paying job in Falls City's booming timber industry. The town straddles the Little Luckiamute River, which was the source of the waterfall after which the town was named. It also provided cheap power for machinery. This power was put to use milling lumber and other products harvested from the remote area.

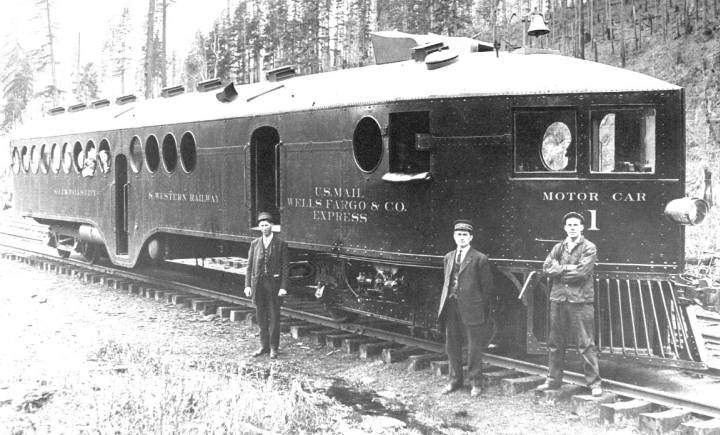

The Falls City & Western Railway, connecting Falls City to Salem was completed in 1903. With the ability to move lumber economically milled from the area's rich forests to market, and to quickly move people into and out of town, the local economy boomed.

By 1921 the population of Falls City had grown to 1,200. The town boasted of fruit farms, bridges over the Little Luckiamute river, banks, a fire department, saloons, a hotel, a movie theater, telephone and telegraph service, a post office, a newspaper, a cemetary, schools, churches, and a hospital.

At this point, word of the opportunities in the area would have reached Salem and Elmer Holloway. He moved the family to Falls City sometime thereafter. The 1930 Census records Elmer, Dorothy, and Kenny living in a house owned by Elmer. Elmer's job was listed as "wood cutter." Dorothy and Kenny were listed as students.

But by 1930 Falls City was already in decline. Overlogging had driven most of the lumber mills to surrounding communities with ready access to trees. The final blow was the closure of the railway's passenger service. The town's population dropped from a peak of 1,200 to just 500 in 1930. The jobs that remained would have been hard to come by.

Despite the economic trouble in Falls City and the loss of the passenger rail connection, it appears that the Holloways continued to live there. In 1932, Dorothy sang the song Sweet Oregon at her eighth grade graduation from a Falls City school.

By 1934, the family had moved back to Salem. A local paper reported Kenny's straight A record at Salem High School for the preceding period (The Capital Journal December 17, 1934). The next year, Kenny graduated. None of the yearbooks from that period list the names of Kenny or Dorothy, nor do their photos appear, either individually or in Salem High's various student organizations.

In 1935, Kenny and Elmer lived together at 1175 N 17th. Elmer's occupation was "wood," but he is also listed under "Fuel Dealers - Retail." Perhaps Elmer had returned to the profession he'd taken up in Phoenix.

Yet another blow would strike the Holloway children in 1936. Dorothy was declared insane and committed OSH, the same facility her grandfather had been committed to thirteen years earlier. The exact circumstances are unclear. According to Dorothy's file, which I obtained from OSH, the petitioner was Elmer Holloway, who claimed that Dorothy was "aloof, inapproachable, distant" and that she lacked judgement. Dorothy claimed abuse and neglect by Elmer, and that he had beaten her, pointed a shotgun at her, and was trying to poison her. It's disturbing how easily a young person's life could be ruined with the flimsiest of evidence.

Dorothy also claimed that "an aunt" was trying to cheat her out of an inheritance. The staff at OSH dismissed most of Dorothy's statements as fabrications. If they were aware of the extent or bitterness of the Blinston family's legal wrangling over Albert's estate, or the magnitude of the money involved, the staff made no mention of it.

The staff would later dismiss complaints of pains and discomfort like they had dismissed Dorothy's claims of abuse, attributing the symptoms to her being "high-strung" and having an active imagination. By the time that Dorothy's extensive metastatic cancer became known, it was too late. On autopsy, the coroner noted that tumor had nearly replaced many of the organs he examined.

This horrifying story deserves much more detail than I'm able to give here. For now suffice it to say that Dorothy died in OSH on August 25, 1966. Her confinement there and failed attempts to get out would involve Kenny on and off throughout his life.

Although he emerged from this childhood much better off than his sister, the years following high school were likely challenging for Kenny. From 1935 to 1937 the Salem city directory listed his occupation as "driver." Kenny lived with Elmer, who was also a driver, so it's possible they worked together and that work might have taken them out of town. If so, this could explain their disappearance from the public record until 1940.

By 1941, Kenny was starting to see education as a path to something better. Boeing was recruiting dozens of young men from Salem's vocational training programs. The company had experienced explosive growth at its Seattle, Washington plant and was having trouble finding workers locally. Communities like Salem filled the gap (The Seattle Star January 1, 1941). Kenny enrolled at the Salem Vocational Training Center, no doubt having heard about Boeing's hiring spree and the short path to joining the company.

The program's coordinator, C. A. Guderian explained the requirements to The Oregon Statesman on January 11, 1941:

… The trainee must be between 18 and 25 years of age, a high school or trade school graduate or be an apprentice in a recognized mechanical trade. He must have taken two years of shop work and mechanical drawing with at least one year of the latter. He must have had work experience in some situation which shows his inclination to become a mechanic. … He must show his vocational training record card showing hours spent in course of aviation sheet metal, which is furnished by the training school here on satisfactory completion of the course.

Around August 20, 1941, Kenny left for Seattle, part of a group of 18 from Salem who would work at Boeing (The Capital Journal August 10, 1941). According to the Seattle city directory, he moved into 6710 Corson Ave., and would work as a Boeing engineer into 1942. The house lies walking distance from what would become the Boeing Flight Test and Operations center.

Kenny was drafted 1941, before his departure from Salem. On May 11, 1942 he returned to Salem where the next morning, he headed to Portland and the enlistment center there. There Kenny enlisted in the US Army. His occupational designation was "semiskilled structural- and ornamental-metal workers," hinting at what he might have done for the Army during World War II.

No public records of Kenny's World War II deployments, training, or activities exist. I understand that it's possible to obtain service records for family members though the National Archives, and have made a request. Unfortunately, a series of unfortunate events and outright incompetence over the last few decades at the Archives mean that this route to the records seems likely to fail. There are other options, which I'm pursuing.

According to the Salem Capital Journal, Kenny was discharged on December 3, 1945, leaving through Fort Lewis in Washington state. Fort Lewis was a major disembarkation point for service members in late 1945, so Kenny would likely have been one in a crowd of hundreds or thousands heading home after the war.

Kenny's rank at discharge was reported as "Tech 4," which I interpret as Technician Fourth Grade (aka "T/4" or "Tec 4"). According to Wikipedia, this was a special rank created by the Army in 1942:

Those who held the T/4 rank were addressed as "sergeant" …Technicians represented a wide variety of soldiers with specialized technical skills, including medics, radio operators and repairmen, mail clerks, mechanics, cooks, musicians, and tank drivers. Initially, the three technician ranks held non-commissioned officer status. However, as technicians received no formal NCO leadership training or qualifications, their entrance into the NCO ranks resulted in organizational confusion, dilution of the NCO corps, and lowered morale among senior NCOs. Consequently, the Army revoked NCO status from technicians in November 1943.

Family oral history holds that Kenny disliked the military, saying "the only good thing it did for me was the GI Bill." And it would be the GI Bill that led Kenny to Hanford.