Physical and Cognitive Impairments

It may be hard to believe, but being diagnosed with a terminal illness whose median survival time is measured in months was not my biggest worry by late March 2023. Far more troubling was how far down the physical and mental fitness ladder I'd tumbled. I'd entered the ER just days earlier with coordination problems. Not only were my physical symptoms now much worse than before brain surgery, but new mental impairments had surfaced.

The most obvious problem was that I could no longer walk without assistance. If you're fortunate enough to have never experienced this condition, consider just how much of your day absolutely depends on your ability to walk effortlessly, independently, and safely. Losing this ability left me dependent on others for simple tasks like getting out of bed, dressing, and using the restroom.

Nor was this just a case of subjective post-operation blahs. My medical record notes that an occupational therapist determined an AMP-PAC (Activity Measure for Post Acute Care) Daily Activity Impairment rating score of 14-19, translating to an impairment of 50-59%.

It's one thing to experience this level of physical disability when you're expecting it. But it's an entirely different matter to be blindsided with it. At no time do I or my family recall having been told to expect anything close to what I was experiencing. On the contrary, we'd been told that some patients were discharged from the hospital the next day after an operation like mine.

My path was clearly headed in a completely different direction than those lucky patients.

My first physical therapy session happened in the hospital a few days after surgery. As I remember, it started simple. Try lifting your left leg (with effort, barely). Try lifting your right leg (much easier). Now rub your left leg on your right shin. Owwww!!

My body was festooned with so many tubes, wires, and needles that I neglected the cannulas that had been inserted into my ankles, and which still stuck out. I was told that this helped the surgery team by enabling injectable access from either the head or foot of the gurney. But in the delicate state of still having those long, sharp objects stuck in my ankles, rubbing anything anywhere in the vicinity was just not going to work.

After a few PT sessions, I'd reached the point where I could walk with a walker. But this took my full, undivided attention. I used my upper body strength to compensate for severe lower body weakness. My left knee hyperextended (or buckled) randomly. As I shuffled the walker forward, straining to keep from falling over, my feet seemed to have separate agendas altogether, constantly fighting each other for the same real estate. Later I'd be told that the best I could hope for in my recovery was to "walk with a brace."

Even with all this going on, I wasn't fully aware of just how disabled I was. This ignorance of my condition would set up yet another terrible healthcare experience. But more on that later.

I found out that I was scheduled to receive something called "speech therapy." Like the nonchalant talk about my "neuro-oncologist," it was far from clear why this was planned. I wasn't slurring my words, had no trouble finding them, and could understand whatever was said.

It turns out that "speech therapy" is an umbrella term that includes cognitive assessment. Viewed from this angle, the reason for my speech therapy sessions would become painfully clear.

Hints of cognitive decline were obvious within hours after my awakening. I remember being asked what year it was. I tried hard but just drew a blank. I was able to set a lower bound (the year of my birth), but otherwise it could have literally been any year at all as far as I was concerned.

You may be thinking, "Ah, that was just the post-anesthesia fog. It happens to everyone."

A fine hypothesis, but it's inconsistent with the trouble I would continue to have for many days thereafter. At least twice daily I was asked to report the current date, but couldn't do it. Not the day of the week. Not the month of the year. Not the day of the month. At least I could not reliably report all of them at the same time.

I would eventually realize that my room had a whiteboard, on which was written the current date. So I could just read the date when asked. I would end up falling back on that trick a lot in the days ahead, but not as much as I could have. It's one thing to be aware of a trick and quite another to remember to use it. Yet another glimpse into my cognitive decline.

Along the same lines, I could not recall my age in years. It seemed like every therapist or doctor I met was keenly interested in this topic. But I could never come up with the number and so ended up just guessing. Several days later I'd discover that I couldn't even do the long subtraction to get the answer.

Simple arithmetic in general turned out to be a big problem for me in the days ahead. On an early cognitive assessment I was asked to subtract seven from one hundred, then seven from the result, and so on for as long as I could. I couldn't even manage two iterations.

Troubling though this problem with basic arithmetic may have been, the cognitive test that freaked me out the most was this: draw the face of a clock. You're kidding, right? You do realize I hold a PhD — in chemistry no less? I draw things way more complicated than clock faces for a living.

Whatever. Let's start with the circle. Here's the dot in the middle. Now for the numbers to finish this pointless exercise…

It was at that moment that the gravity of the situation hit me. First, I'd made the circle way too small to fit everything in. Second, I only drew numbers on one side of the circle (the right, if I recall). Third, everything was smashed together. I suspected I'd made a mess of the exercise, but only knew how and why when the therapist explained what I'd done.

I was asked to try again, but this time making the circle outline larger. I flipped the page over and started again. BIG CIRCLE. Now, what about those numbers? My stomach knotted, my face flushed hot, and I could feel the prickly sensation of sweat breaking out under my gown. I couldn't do it. Where should I place the numbers? How many were there again? Why does that five look out of place? And why do I suddenly feel so very tired? Nononononono.

I'd go on to bomb test after test like this. There are too many to list them all, but here's one more example. I was given a piece of paper onto which were drawn several horizontal and vertical lines. My task was to cross each horizontal line by drawing the complementary vertical, thus forming a plus symbol (+). Simple for everyone else, but not for me. I ended up ignoring most of the left-hand side of the page. Only when this was pointed out to me did I realize the mistake.

Later I'd learn that "cancellation" is a standard neurological test for certain kinds of brain damage.

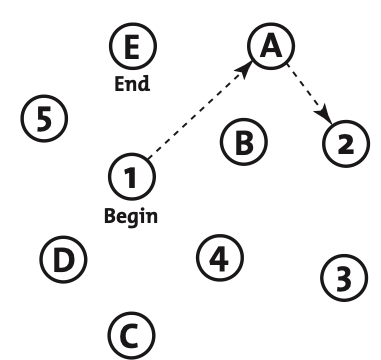

Here's another example of a test I bombed. Complete the pattern below by drawing the remaining arrows. You're supposed to deduce the pattern: number; letter; number; and so on. At the same time, you're supposed to increment the preceding circle's content (A to B, 1 to 2, and so on). As I pondered where to draw the third arrow, I experienced the same sense of sluggishness and uncertainty I had when drawing clock faces.

This particular test is part of the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MOCA). The MOCA was in the news a few years back because a certain US president made a big fuss after claiming to have "aced" it. I was apparently no smarter than that guy now.

Of course, the strike I had against me was a recent brain surgery and its disruption to my right parietal lobe. Many, possibly all, of my symptoms were consistent with the resection of a lemon-sized tumor from that region of my brain. Even so, this knowledge did little to silence the voice in my head that kept asking: Is this ever going to get better?

I'd spent my entire adult life on my education and mental fitness. I had done what I could to keep my body in good condition. Within the span of just one week it seemed I'd lost it all. Not only was this disease going to kill me within a matter of months, but it had just stolen my two most prized possessions.