Reflections on My Brain Surgery

There are no doubt images more disturbing than parts of one's own brain being sliced off and extracted through a hole cut into the skull, but on the morning of March 28, I couldn't think of any. Over the span of just five days I'd gone from a more or less normal guy with odd coordination issues to a hospital patient with a cancerous brain tumor the size of a lemon. Leaving the thing there was a non-starter; I was told I'd be dead within three months. The entire situation seemed outrageous, ludicrous — like the pretext of a bad movie. As surgery time barreled down on me, I was struggling to understand how things could have gone so wrong so fast.

I have a few memories of the hours prior to surgery. I took a shower. Afterward, I scrubbed my upper body with a special kind of disinfectant wipe. None of my hair was cut, nor would it be. Instead, my scalp, hair and all, would be cut, peeled back, and then later joined with glue and staples.

I drank a cupful of Gliolan solution. If it had a flavor, I don't remember. Much more remarkable was the reason for doing it.

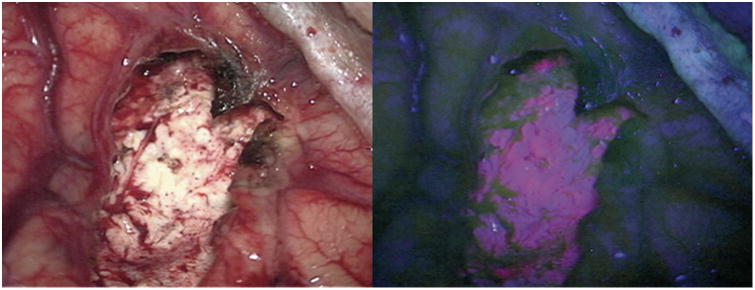

Gliolan is the trade name for 5-aminolevulinic acid (5-ALA). It's a low-molecular-weight ketone-containing amino acid. 5-ALA readily crosses the blood-brain-barrier, and into the brain where it is taken up by tumor cells and metabolized to protoporphyrin IX (PPIX). The violet-red fluorescence of this substance allows cancerous and healthy brain tissue to be distinguished in real time under a microscope.

The surgery was be guided by of magnetic imaging. However, MRIs can't always tell the difference between tumor and healthy tissue. The goal of my surgery was "maximal safe resection." In other words, eliminate as much tumor as possible, without touching healthy tissue. The use of Gliolan increased the odds for success.

Soon after downing the pink drink, the tumor buried deep inside my brain began to accumulate PPIX and with it the ability to fluoresce, marking it for removal by the surgery team. Adios, mofo!

I didn't know it at the time, but Gliolan has a side effect that, although minor, would set up one of the worst medical procedure experiences of my life. But more on that later.

Some time before 7 AM I was brought to surgery. A sign bearing the text "Operating Room 13" marked the entrance. "That's my lucky number," I remember saying out loud in a futile attempt to calm down. What kind of sick joke is this? Operating Room 13? Having had some time to think about it, I now think I should have been reassured. In this hospital we deal with facts. Leave your superstitions at the door and get to work.

The doors swung open and I was wheeled in. The room was dominated by two motifs: a large rectangular observation window along one wall and at least one massive concave lighting fixture composed of hexagonal elements. It reminded me of the James Webb Space Telescope. I asked if any music would be played during the procedure and was told "Whatever the scrubs put on." I laughed.

I remember speaking with two people immediately before surgery. One was the anesthesiologist. The other was a neurologist charged with monitoring electrical signals running between my brain and extremities. The technique involves the use of Somatosensory Evoked Potentials (SSEP). The idea appears to be similar to a continuity test you might do while working on a car's electrical system. Leads attached to various parts of my brain would report the results of stimulation at the extremities. Continuous monitoring of these signals would set up an early warning for damage to "eloquent" pathways. I asked the neurologist if I'd remember the conversation and was told "probably not." I was pleased and amused to find that I did remember after all.

Realtime monitoring with SSEP and other techniques is essential for tumor resection under general anesthesia. The alternative would have been an awake craniomoty, in which my brain would literally be exposed and manipulated as I was given instructions for actions to perform and sensation to report. I have a disconnected memory of being told at some point that such surgeries, although routinely performed, can lead to post-traumatic stress disorder. I was thankful to be skipping at least this room of the chamber of horrors I found myself trapped in.

My transition to general anesthesia was uneventful. I was told that a mask would be placed over my face and it would smell like the inside of a beach ball. It was and it did. I asked if I should count backward from ten and was told "If you'd like." I don't think I even finished saying the word "nine."

The Report

Weeks later I was able to track down a detailed account of the surgery, written by Dr. Staff Surgeon and apparently also Dr. Assistant Surgeon. The report begins with some preliminaries:

- I was intubated, anesthetized, and catheterized.

- I was pinned into a Mayfield clamp. It's a little surprising to see a review from just two years ago laying out best practices for this widely-used immobilization device.

- I was administered a preoperative high-resolution MRI, registering surface landmarks on skin and scalp.

- A barn door incision (be warned) was planned.

- I was given "a precordial Doppler to monitor for air embolus given that this craniotomy spanned the sagittal sinus."

And then the main event:

Surgery began with a linear incision above the superior temporal line down through the galea. The occiptal artery and the superficial temporal artery were not divided in this approach. The skin ws retracted laterally and meticulous hemostasis was obtained. A precranial graft was then harvested and based medially toward the sagittal sinus in case it was needed for either dural or sagittal sinus repair. … Two bur holes were also placed laterally. The dura was stripped liberally, and a craniotome was used to connect the bur holes, turning a wide craniotomy. Again, no injury to the sinus or the dura was performed with this maneuver. I then brought in the operative microscope for the remaining duration of the procedure. I continued under the microscope.

The report continues by explaining the path that was dug from the surface of my brain to the tumor buried within:

Brain relaxation was excellent at this point, and I could see pulsatile dura without any fullness within the brain. I created a small durotomy laterally and then continued this medially toward the sagittal sinus, where I retracted the sagittal sinus medially. Tack-up stitches were placed to prevent run-in, and I inspected the field. I could see the vein of Trolard coursing over the anterior portion of my exposed field, which landmarked the central sulcus. I had also exposed enough brain with this to see the postcentral sulcus as well as the precentral sulcus. I mapped the tumor with navigation and remaining behind the postcentral sulcus, entirely within the cuneate sulcus in an attempt to mitigate any injury to eloquent sensory and motor structures. Working medially, I created a small corticotomy in the brain and traversed middle normal brain tissue until I reached the surface of the tumor. The tumor itself was gray, friable, hemorrhagic, and I worked quickly with bipolar cautery as well as the ultrasonic aspirator to debulk the internal portions of the tumor. There were several flow voids which were confirmed with MRI that represented dilated veins within the tumor. These were confirmed first with navigation and then direct microdissection to confirm that these were not en passage or eloquent arteries that coursed towards the tumor. Once this was confirmed, we worked to cauterize and divide them, which aided in additional debulking.

I suspect that the appearance of the tissue being removed ("gray, friable, hemorrhagic") adds confirmation that the right stuff was being taken out at a macroscopic level.

Remember the pink drink? Here's where it comes into play:

Debulking was aided with 2 technologies. I used the fluorescence with the 400 nm filter given that the patient had taken 5-ALA 2 hours prior to anesthesia induction. Tumor fluoresced pink under this light and aided in resection. Additionally, the intraoperative ultrasound was used to confirm borders of the tumor anteriorly with eloquent structures, and I used a monopolar suction stimulator device as well to insure that I was not entering eloquent tissue prior to resecting it either with my cautery or my ultrasonic aspirator. …

Later, the report uses a word that neither I nor my family up to this point remember having heard before, "glioma":

In places, the tumor melted away readily and peeled in sheets, consistent with what I would expect from a glioma.

The rest of the story turns on that one little word. It's no overstatment that had that word been used previously, and if I had understood its implications, things might have taken a different path.

For now, it's enough to note that the surgery report confirms something that was suspected by the surgery team, but about which I was unaware. Namely, that I had not just brain cancer, but the most aggressive, lethal, and least treatable.

The surgeon went on to conclude that all resectable tissue had been removed:

Specifically, I resected medially well enough until I could see the splenium of the corpus callosum, which I left intact. … Similarly, I turned my attention to the lateral, posterior, and medial boundaries of the tumor, and no fluorescence was seen in these areas as well. … I had achieved a gross total resection of the enhancing portions of the tumor as well as any fluorescent portions of the tumor.

As I'll explain later, the surgery team had good reason to steer clear of my splenium. The problem was that imaging indicated that cancer may have spread to this part of my brain. Leaving potentially cancerous tissue intact traded off essential brain function now for the risk of later recurrence.

A few days following the surgery I would learn that the kind of resection described in the report is called "super-maximal." A maximal resection removes all of the MRI contrast-enhancing parts of a tumor. A super-maximal resection goes further by removing non-enhancing tumor tissue as visualized by some method other than MRI. This sounds good, and it was. But I would learn all too well that brain cancer is the kind of football game in which gains are measured in inches, not yards.

With the resection itself complete, all that was left was to secure the piece of skull that had initially been removed:

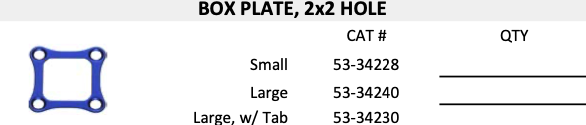

I then replated the bone with a titanium cranioplasty by the Stryker plating system.

The key feature of a craniotomy is that the section of skull removed to gain access to the brain is replaced. However, just pushing the bone into place won't do at al. It could slip and cause all kinds of nasty complications.

From what I gather, something like the Stryker plating system is used to hold the skull fragment in place, allowing it to fuses with its surroundings. In my case, Stryker Box Plate, 2x2 hole (catalog number 53-34240) was installed just under the skin on the back right side of my head. And that's where it will stay, hopefully for the rest of my life.

Coping

Is it unhealthy to seek out (or especially report) these details? I don't think so. Most of my life has been dedicated to feeding an irresistible curiosity for science and technology. Viewing my body, mind, and everything I perceive as reality, when stripped to essentials, as explainable in purely materialistic terms is par for the course. The brain is just where the rubber meets the road if you hold that view. You could say that going through this exercise is how nerds cope, and I wouldn't disagree. Even so, there's more to it.

Messy Business

Dr. Assistant Surgeon would later report to my relieved family that the operation was a success and that he had "got it all." Only slowly would we all come to realize that medical communication is a messy business. Understanding doctors too quickly, and the problems that can cause, would turn out to recurring themes.