Conjugated Cycle Selection

The valence bond model ("VB model") remains widely used in chemistry, and serves as the basis for most molecular representation schemes in cheminformatics. Useful though it may be, the VB model carries some important liabilities. One relates to electron delocalization of the type found in benzene and its analogs. Here, the VB model's exclusive focus on two-atom bonding leads to asymmetry artifacts. This in turn leads to problems in certain applications, most notably canonicalization. Ideally, it would be possible to correct these artifacts using minimal intervention. This article describes one approach.

Delocalization-Induced Molecular Equality

The VB model considers bonding to be a local phenomenon that occurs between two atoms only. This approximation works for many structures across many applications, but it does have one spectacular failure mode. Molecules such as benzene exhibit multi-atom bonding. The VB model can be used to represent benzene and its derivatives, but only by freezing electron density between two atoms at a time. The result is often referred to as a "resonance structure."

In many contexts, this structural mis-specification can be ignored. For example, the exact molecular weight and total particle count of benzene and its derivatives can be computed from VB-based representations with high accuracy and precision. Other descriptors such as molecular formula can likewise be computed.

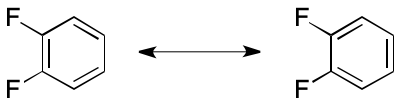

But in some applications, the artifactual asymmetry caused by the VB model leads to unacceptable errors. Canonicalization is a case in point. Consider the canonicalization of 1,2-difluorobenzene (below). Two distinct, yet equivalent, VB structures can be constructed. Canonicalization of VB-based representations demands either the exclusive use of one representation, or a method to suppress asymmetry artifacts.

A previous article associated the term "Delocalization-Induced Molecular Equality" (DIME) with this phenomenon.

The Atom Selection Problem

One technique for mitigating the effects of DIME is atom selection ("selection"). Selection is the process of identifying those atoms that collectively define a node-induced subgraph covering all atoms and bonds leading to DIME. For example, selecting all of the carbon atoms in 1,2-difluorobenzene would yield a subgraph that also included all carbon-carbon bonds.

What happens after atom selection depends on the system. In Balsa (and, by extension, SMILES), a "delocalization subgraph" propagates into the syntax and semantics of string encodings. Ultimately these encodings eliminate asymmetry artifacts that the exclusive use of the VB model would otherwise impose. After selection, the carbon atoms in 1,2-difluorobenzene are all encoded with the same lower case character (c).

Even so, atom selection has its own requirements. A canonicalization scheme would need some way of drawing the line between conjugated double bonds whose atoms must be selected, and conjugated double bonds whose atoms must not be selected. Moreover, selection is not exactly cheap. The next sections explain the cost of selection itself, but the non-negligible costs of de-selection should also be considered. De-selection will be required in several contexts, including translation into non-selectable serialization formats (e.g., Molfile) and 2D depiction. Deselection requires at the very least a maximum matching implementation.

To minimize encoding and decoding costs, the set of selected atoms should be kept as small as possible. The smaller the selection set, the less work is required to decode it. Selecting atoms that don't participate in DIME adds cost to an already expensive set of operations.

Conjugated Circuits

Electron delocalization by itself poses no problem for the canonicalization of VB-based molecular representations. The reason is simple. Without a way to generate multiple equal representations, only one VB representation is possible. The trouble arises from the presence of multiple equivalent localized forms. And this can only occur when delocalization occurs along a cyclic path.

Therefore, a minimal atom selection set can be obtained by adding only those atoms found along delocalized, cyclic paths.

More specifically, we'd like to select all of the atoms that lie on a conjugated circuit. Milan Randić, who introduced this concept in 1976, defined conjugated circuits as "circuits of full conjugation contained in Kekulé forms of a molecule." He later offered the related definition: "Conjugated circuits are circuits within Kekulé valence structures in which there is regular alternation of C=C and C-C bonds." Randić used conjugated circuits to solve several theoretical problems, but they are also well-suited to atom selection.

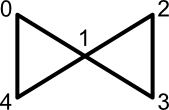

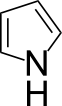

Before moving on to the application of conjugated circuits to atom selection, the difference between "circuit" and "cycle" is worth discussing. In graph theory, both cycles and circuits represent alternating sequences of nodes and edges starting and ending at the same node. But a circuit allows repetition of internal nodes, whereas a cycle does not. The butterfly graph, depicted below, illustrates this difference.

The node sequence (0, 1, 2, 3, 1, 4, 0) represents a circuit. This sequence is not a cycle because internal node 1 occurs twice. However, the node sequence (0, 1, 4, 0) defines both a cycle and a circuit.

Alternatively, consider the set of all cycles to be a subset of the set of all circuits. What disqualifies a circuit as a cycle is the presence of at least one repeated internal node.

In cheminformatics this distinction is largely moot. The repeated node in a circuit must by definition have degree four or higher. In VB-representations, this implies an atomic valence of four or higher. Such atoms can only engage in delocalization through expanded valence (e.g., sulfur). Tetravalence is furthermore often associated with tetrahedral substituent geometry, which tends to block conjugation.

In the context of cheminformatics representations based on the VB model, the terms "conjugated circuit" and "conjugated cycle" can therefore be used interchangeably.

Conjugated Cycle Selection

The definition of conjugated circuit can be combined with an understanding of exactly why electron delocalization poses a problem for canonicalization, yielding a simple procedure for minimal atom selection that I call "conjugated cycle selection":

- Construct the set of all cycles (C) through exhaustive enumeration. Any correct algorithm will do, but the one developed by Hanser et al. is especially attractive for its simplicity of implementation and efficiency.

- For each cycle c in C, test for conjugation. Various electronic factors might be considered here, including whether triple, dative, conformationally restricted, or zwitterionic bonds should be eligible.

- If c is conjugated, select all of its unselected atoms.

Examples

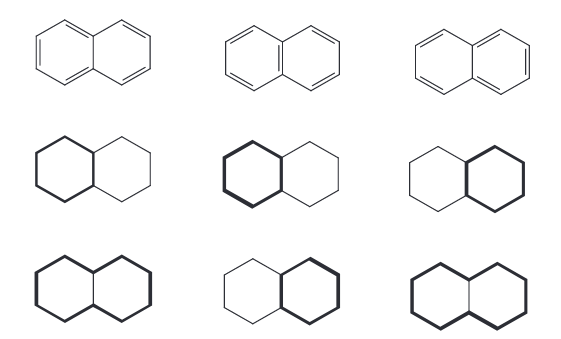

A few examples help illustrate how conjugated cycle selection differs from what might be considered common practice.

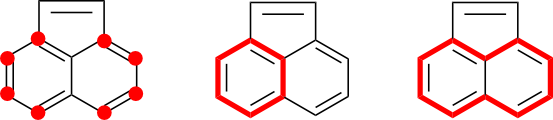

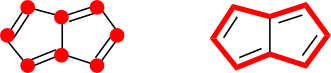

A naive algorithm might select all of the atoms in the acenaphthylene ring system. These atoms are, after all, contained in the same cycle system and connected to each other through conjugated bonds. However, this approach leads to over-selection in that the two atoms across the five-membered ring bridge is unnecessary. This can be recognized by considering the set of conjugated cycles. Neither of the two bridging atoms is contained within a conjugated cycle. These atoms can therefore never participate in DIME. Asymmetry artifacts can be completely eliminated through the selection of only the ten atoms found in the naphthalene core structure.

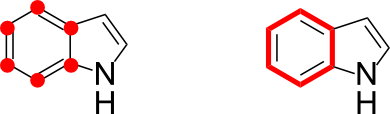

Indole offers another example. One often finds SMILES in which all atoms in both the six- and five-membered rings are selected. In contrast, conjugated cycle selection leads to a subgraph containing only the atoms in the six-membered ring. Selection of other atoms is unnecessary from the perspective of suppressing DIME.

If the atoms in the isolated double bond of indole don't need to be selected, then none of the atoms in pyrrole need be selected for the same reason. Fully-selected pyrrole and imidazole rings are nevertheless common even though such over-selection adds needlessly to the computational burden placed on readers.

Conjugated cycle selection is especially useful for cases in which the Hückel 4n + 2 rule might seem difficult to apply. Take, for example, pentalene. Although the 4n + 2 rule as taught in undergraduate organic chemistry courses does not apply to fused cycles, it often is used anyway. In the event, pentalene's 8 π electrons might discourage atom selection because of the 4n + 2 violation. Yet two equivalent VB structures are possible for substituted analogs, and DIME is clearly possible. Conjugated cycle selection alerts us to this fact by finding the eight-membered conjugated cycle containing all of the molecule's atoms.

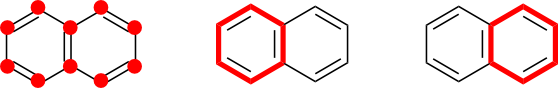

It might seem as if conjugated cycle selection could fail for naphthalene in some cases. If so, recall that naphthalene contains three cycles: two of length six (six atoms), and one of length ten (ten atoms). Regardless of the exact VB-structure drawn, two of these cycles must be conjugated. Therefore, all of naphthalene's atoms will be selected if the set of all cycles is used, regardless of the specific VB representation.

Naphthalene also illustrates why the set of all cycles must be used. Cycle basis sets such as the smallest set of smallest rings (SSSR) are not suitable because they omit some cycles. Those missing cycles may be conjugated, which would lead to under-selection.

Previous Work

The idea of minimal atom selection was explored earlier by Mann and Thiel in Kekulé structure enumeration yields unique SMILES. The approach differs from the one described here, but shares the use of the set of all cycles.

Conclusion

Atom selection offers a way to patch the failures of the VB model so that representations based on it can be canonicalized. However, this raises the new problem of efficient atom selection. Basing selection on the set of all conjugated cycles offers a straightforward, correct, and minimal solution.