Balsa Reference Implementation

SMILES is a compact molecular serialization format used widely in cheminformatics and computational chemistry. Even so, the published documentation incompletely describes SMILES, making the implementation of software impossible without some degree of improvisation. Balsa is a fully-specified language subset created to solve this problem. To bridge theory and practice, work on a Balsa reference implementation is well underway. This article offers a high-level overview of the software.

About Balsa

Balsa seeks to improve SMILES in the following ways:

- Constrain all numerical quantities with upper and lower bounds.

- Express syntax via formal grammar.

- Define all major computations and analyses, including implicit hydrogen count and stereo descriptors.

- Eliminate rarely-used or redundant features.

- Guide the implementation of readers and writers.

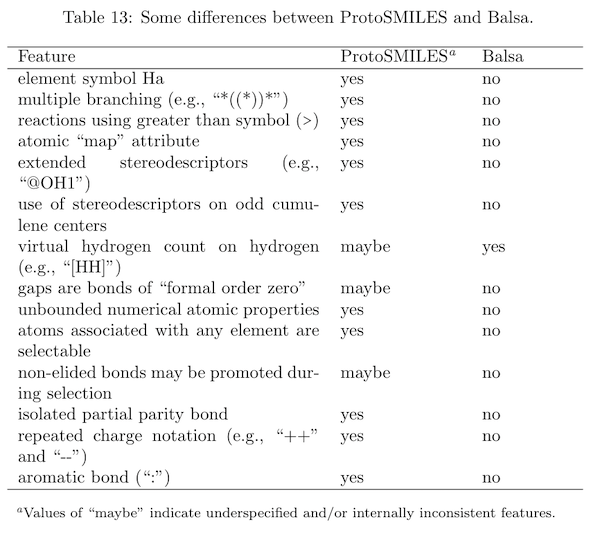

A working paper, Balsa: A Compact Line Notation Based on SMILES, details these points. Included is a table summarizing the differences between Balsa and ProtoSMILES, a SMILES protolanguage.

Balsa adds no features to SMILES, setting it apart from the two other SMILES documentation efforts (OpenSMILES and SMILES+). In other words, Balsa is designed to be forward compatible with SMILES. This means that SMILES software can correctly process all Balsa output, but Balsa software can correctly process only some SMILES software output.

Balsa Reference Implementation

The Balsa reference implementation's source code is available on GitHub and the software can be installed through crates.io.

Wikipedia defines a reference implementation as:

… a program that implements all requirements from a corresponding specification. The reference implementation often accompanies a technical standard, and demonstrates what should be considered the "correct" behavior of any other implementation of it.

Consistent with this definition, the Balsa reference implementation seeks to demonstrate the correct implementation of all language features. The software is licensed under the liberal MIT License. Rust was selected as the programming language to maximize portability, programmer ergonomics, and type safety.

It's sometimes helpful to distinguish Balsa the language from Balsa the reference implementation. The terms "Balsa language" and "Balsa software" will be used, respectively, to do so.

Data Structures

One of Rust's many selling points is a powerful type system. When paired with type-driven design, errors that would otherwise make their way to run time are instead caught at compile time. Data structures provide the crucial link.

Balsa supports two data structure paradigms: molecular graph and molecular tree. A molecular graph typically maps atoms to nodes, and bonds to edges. Popular though this paradigm may be, it is not the most natural expression of the Balsa language. Molecular trees fill this role. A molecular tree is a tree-based data structure in which any two nodes are connected through a continuous path. To enable the interconversion of tree- and graph-based representations, Balsa supports both paradigms.

For convenience, the software's data structures are named after the terms used in the working paper.

Molecular Tree

The types comprising Balsa's molecular tree data structure can be found in the tree submodule. Perhaps surprisingly, no data structure representing an actual tree is defined. Instead, the top-level data structure tree::Atom is defined. Its presence alone fully defines a molecular tree.

pub struct Atom {

pub kind: AtomKind,

pub edges: Vec<Edge>,

}

Just two attributes, kind and edges suffice. AtomKind is an enumeration of the kinds of atoms supported by the Balsa language. Just four variants are possible: Star, Shortcut, Selection, and Bracket. The last three of these contain data themselves, an example of Rust's support for sum types. The names of each variant track the names used in the Balsa working paper. edges is an ordered list of edges defining connectivity and bonding.

pub enum AtomKind {

Star,

Shortcut(Shortcut),

Selection(Selection),

Bracket(Bracket),

}

The variants of AtomKind are mutually exclusive, meaning that the Rust compiler will prevent the construction of most invalid atomic states. Compare this to a "bag-of-attributes" approach in which Atom were a struct having the attributes element, charge, and so on. Such a representation would make it possible to encode, for example, a selected titanium atom. AtomKind makes this impossible, and the Rust compiler enforces this prohibition.

One of the main advantages of the tree data structure is memory efficiency. Whereas a graph requires edges to reference source and target atoms by index, a tree allows edges to "own" child nodes directly. This relationship is captured by the Atom.edges attribute.

pub enum Edge {

Bond(Bond),

Gap(Atom),

}

A tree::Edge is an enumeration with two variants, Bond and Gap. The names of these variants match the terms used in the working paper. Bond designates connectivity with bonding, whereas Gap designates connectivity without bonding. The variants of Edge are mutually exclusive, meaning that invalid states can not be encoded. For example, a Bond can connect an Atom to another Atom or a bridge node. However, a Gap can only connect two Atoms.

tree::Atom and tree::Edge implement convenience methods to aid construction. For example, a "star" atom having a single child connected through an elided bond ("**") would be represented like so:

assert_eq!(

tree::Atom::star(vec![tree::Edge::elided_star(vec![])])

Atom {

kind: AtomKind::Star,

edges: vec![

Edge::Bond(Bond {

kind: BondKind::Elided,

target: Target::Atom(Atom {

kind: AtomKind::Star,

edges: vec![]

})

})

]

}

)

Molecular Graph

A graph representation is useful when converting to and from graph-based formats. For example, direct translation of molfile into Balsa might work better with a graph representation rather than a tree. The graph submodule contains data structures helpful for such translation.

Perhaps surprisingly, the graph submodule does not contain a top-level data structure representing a molecular graph. Instead, a molecular graph is encoded as an ordered list of graph::Atom values (Vec<graph::Atom>).

pub struct Atom {

pub kind: AtomKind,

pub bonds: Vec<Bond>,

}

The two attributes, kind and bonds serve similar roles as in tree::Atom.

Follower

Tree- or graph-based representations are usually constructed to analyze some aspect of molecular structure. Many analyses will require some form of traversal. For example, writing a Balsa string requires traversal. So does reading a string, if looked at in a certain way. Conversion between graph-based and tree-based representations also requires traversal. Tree-based representations are in particular likely to require traversals for even simple tasks such as molecular weight calculation.

A depth-first traversal will be suitable in many contexts. Although the underlying algorithm is not complex, it isn't easy to implement, either. Ideally, depth-first traversal would be implemented once, allowing the same traversal to be used in many contexts. In this way traversal can be decoupled from analysis.

The key to this design is Follower. Follower is a trait that can be implemented by any Rust type. Doing so allows instances of the type to perform an analysis on the depth-first traversal of either a molecular tree or graph.

Follower defines just five methods:

pub trait Follower {

/// An Atom disconnected from the previous atom was encountered.

fn root(&mut self, root: &AtomKind);

/// An Atom bonded to the previous atom was encountered.

fn extend(&mut self, bond_kind: &BondKind, atom_kind: &AtomKind);

/// An Atom closing a cycle was encountered.

fn bridge(&mut self, bond_kind: &BondKind, cut: &Bridge);

/// A branch was encountered.

fn push(&mut self);

// The end of a branch was encountered.

fn pop(&mut self);

}

Follower is extremely flexible. Its methods can be called via an actual depth-first traversal, or through a procedure that simulates one. And of course, the work that gets done for each method invocation is entirely up to the implementing type.

The idea behind follower is easy to confuse with the Gang of Four "Visitor" Pattern. The goal of that mis-named pattern is to implement double-dispatch for languages that don't do so natively. As the authors put it, "Visitor lets you define a new operation without changing the classes of the elements on which it operates." That's not quite the intent with Follower, which is to separate the traversal of a data structure from actions to be performed at each step.

Reading Strings

Reading a Balsa string requires just a string value and a mutable Follower instance. Passing references for both to the read::read function exercises the Follower API. What happens as those method are called depends, of course, on the implementation.

For example, a tree can be built from a Balsa string by using the Follower implementation defined by tree::Builder.

let string = "**";

let mut builder = tree::Builder::new();

read(string, &mut builder);

assert_eq!(

builder.build(),

Atom::star(vec![Edge::elided_star(vec![])]),

)

Replacing tree::Builder with graph::Builder allows construction of the graph representation instead.

Writing Strings

Writing a Balsa string requires a tree or graph representation and a Writer instance. Writer implements the Follower trait, allowing use wherever a Follower works. For example, the following uses the tree::walk function to write a tree representation as a string.

let root = tree::Atom::star(vec![tree::Edge::elided_star(vec![])]);

let mut writer = follow::Writer::new();

tree::walk(&root, *mut writer);

assert_eq!(writer.write(), "**")

Walking Trees and Graphs

Tree and graph representations can be traversed in depth-first order using the tree::walk and graph::walk functions, respectively. Each function takes a reference to a representation and a Follower. On completion, the Follower is interrogated to reveal the analysis. As noted in the previous section, writing strings can be accomplished by pairing a Writer with walk. As another example, consider the transformation of a tree into a graph ( recall that Builder implements Follower):

let root = tree::Atom::star(vec![tree::Edge::elided_star(vec![])]);

let mut builder = graph::Builder::new();

tree::walk(&root, &mut builder);

assert_eq!(

builder.build(),

vec![

graph::Atom::star(vec![graph::Bond::elided(1)]),

graph::Atom::star(vec![graph::Bond::elided(0)])

]

)

Short-Term Work

Although Balsa implements all low-level language functionality, some high-level features are currently missing. The two most important pending feature sets to be added in the short term are:

- Computing implicit hydrogen count and subvalence. Both

graph::Atomandtree::Atomshould fully implement the algorithms described in the Balsa working paper. Entries to both can be found in the obsolete Purr and Dialect repositories. - Selection and deselection. Implementing both processes would enable interconversion of selected and deselected forms for use in canonicalization and other DIME-sensitive applications.

Long-Term Work

The availability of a reference implementation puts some long-term goals within reach, in particular:

- Validation suite. This would consist of an automated test suite containing Balsa string inputs and expected outputs for computations including virtual hydrogen count, bond conformation, atom configuration, and atom connectivity. Using the validation suite, the correctness of other Balsa implementations can be checked.

- Performance benchmarks. Efficient implementations will require some iteration. The reference implementation can be useful here as a benchmark.

- Direct molecular translation. Balsa can be used as a component in a larger suite of tools for direct molecular translation. The idea here is to maximize the number of features that can be translated by avoiding intermediate representations. Toward this end, Balsa can be paired with Trey and other format-specific toolkits yet to be published.

Conclusion

Balsa is a compact molecular serialization format based on SMILES. A reference implementation supporting all basic operations is now available. Over time, this software can be used to develop other Balsa implementations. Integration into translators and other cheminformatics applications is also possible.