Beyond Stereochemical Templates

Stereoisomerism is an essential component of molecular structure. But chemistry's ability to devise new stereoisomer forms long ago outstripped the ability of mainstream cheminformatics tools to represent them. Anything more complicated than tetrahedral configuration or alkene conformation often presents a challenge. This problem will ultimately be solved by generalized approaches to stereochemical representation. Although efforts over the last few decades have made progress, the results have not been widely adopted due to unwieldy formulations. This article offers a fresh approach to the problem that builds on the familiar.

A Note about Configuration

Before getting into the topic at hand, a few words on terminology can save a lot of confusion. The words "configuration" and "conformation" are used here in very specific ways that sometimes differ from uses in other contexts. Both refer to relative geometrical arrangements of atoms. Both relate to stereoisomerism. However, the words are not interchangeable. The difference comes down to how isomers can be interconverted. Conformations can be interconverted through rotations about an edge, which is typically equivalent to a bond, whereas configurations can not.

Tetrahedra are Easy

The tetrahedron is a workhorse stereochemical representation. It's a template, meaning that substituents about the stereocenter are imagined to fit into a preconfigured geometrical pattern. A tetrahedron offers two unique arrangements. The difficulty is not so much enumerating them but rather representing them in a machine-readable format.

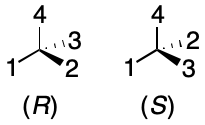

The most popular approach is the Cahn-Ingold-Prelog (CIP) system. CIP assigns a score to each substituent based on a set of atomic invariants These invariants include properties such as atomic number, mass number, unsaturation, and cycle membership. After assigning scores to each substituent, the right-hand rule is applied. The fingers of the right hand wrap the lowest-priority substituents in increasing order. If the thumb points toward the fourth substituent, the value (R) is assigned. Otherwise the value (S) is assigned.

Cheminformatics toolkits and serialization formats use a streamlined version of this approach. Molecular representations, being based on graphs or trees, can take advantage of a built-in atomic ordering. This sidesteps the need for invariants and the many complexities they bring. Ordering can be explicit, as in the case of atomic indexes assigned for molecular graphs, or implicit as in molecular trees.

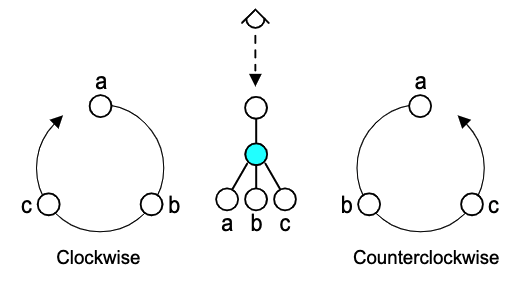

Take for example, Balsa, a subset of SMILES. The stereodescriptors Clockwise ("@@") or Counterclockwise ("@") are assigned by sighting along the bond from a parent atom to a child atom stereocenter. The direction of iteration (clockwise or counterclockwise) for the stereocenter's children determine the descriptor.

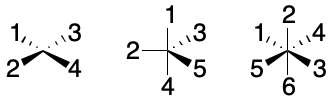

The ProtoSMILES dialect of SMILES extends this system with templates beyond the tetrahedron. The approach was later adopted by the OpenSMILES dialect for square planar, trigonal bipyramidal, and octahedral configurations. The complexity of representation and interpretation of these templates increases markedly with the number of substituents. Roger Sayle recently presented some work aimed at bringing these more diverse templates to a wider audience through RDKit. Work aimed at incorporating more diverse templates into InChI was performed by Alex Clark.

The Trouble with Templates

A stereochemical template assumes a predefined geometrical arrangement of substituents about a stereocenter. The approach is expedient, but it's also brittle. Organometallic, inorganic, and even organic species exhibit many kinds of stereochemically-relevant atomic arrangements. Each one requires its own unique template together with its own rules of construction and interpretation. Because the set of templates is unbounded, no implementation using them can ever be complete.

What's needed is not a comprehensive catalog of stereochemical templates, but a generalized method of stereochemical representation that eliminates the need for templates altogether.

Projection

The generalized method for stereochemical representation presented here is based on projection. In projection, the three-dimensional coordinates of a stereocenter's substituents are projected onto a plane intersecting the stereocenter. From a projection, generalized stereodescriptors can be constructed.

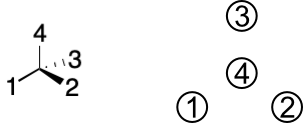

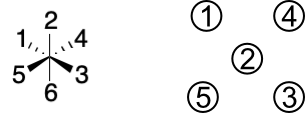

The idea of projection isn't new, just hiding in plain sight. Consider a stereocenter with a tetrahedral arrangement of substituents. We can produce a projection by following these steps:

- Identify the stereocenter.

- Place the stereocenter into a plane.

- Choose a substituent (the "prime" atom).

- Orient the prime atom so that its bond to the stereocenter extends perpendicularly above the plane.

- Project the prime atom down into the plane.

- Project the remaining three substituents up into the plane.

Notice how simple it would be to obtain a Balsa stereodescriptor from a projection. At Step (3), the prime atom is the substituent with the lowest global order. Having made the projection, we find the atom with the next lowest order. Then we set the stereodescriptor based on whether the remaining two atoms sweep in the clockwise or counterclockwise directions when traversed in order.

The first step toward generalizing this concept is to relax the above rules to accommodate not just a tetrahedron, but any other arrangement such as octahedral, square planar, and trigonal bipyramidal. Relaxations might include:

- Project non-prime substituents lying above the plane.

- Account for non-prime substituents lying in the plane.

- Ignore a non-prime substituent lying directly below the prime atom.

Consider the projection for an octahedral stereocenter. Like the tetrahedral projection, it places the prime atom at the center of an arrangement in which the remaining equatorial substituents are separated by arcs of π/2 radians.

This projection is a good first step, but still incomplete. To understand why, consider a bizarre new form of octahedral configuration in which alternate equatorial ligands were not separated by π radians, but some other angle. We'd want to capture the distinction, but that would not be possible with just the projection above.

Coordinate System

The projection of substituents places points onto a plane. As we'll see, generating a descriptor requires a method for referring to these points. A convenient approach is to develop a coordinate system. It should be detailed enough to uniquely locate a substituent but minimal to allow for compact notation.

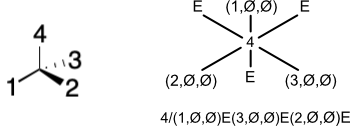

Projection of a substituent creates a position in the projection plane. This position can be occupied by atoms originating from one of three locations: above the plane; below the plane; or in the plane. A given position can therefore be represented by a coordinate expressed as a tuple of the form ("x,y,z)" where where x is the order of an atom below the projection plane, y is the order of an atom in the projection plane, and z is the order of an atom above the projection plane. If no atom from a given region is present, we use the null symbol (Ø).

To accommodate substituents that are colinear with the stereocenter, a distal position is created. A distal position is situated π radians from a projected substituent. If not already present, a distal position is created whenever an atom is added to a position. The distal position may be empty, yielding a coordinate of "(Ø,Ø,Ø)" which can be shortened to the capital letter "E".

Generalized Stereodescriptor

Given the technique of projection and a coordinate system that can describe projected substituents, a generalized stereodescriptor can be formulated. Its purpose is to uniquely and adequately represent the substituent configuration about a stereocenter. At a minimum, the stereodescriptor should include representations for the prime atom and all substituents.

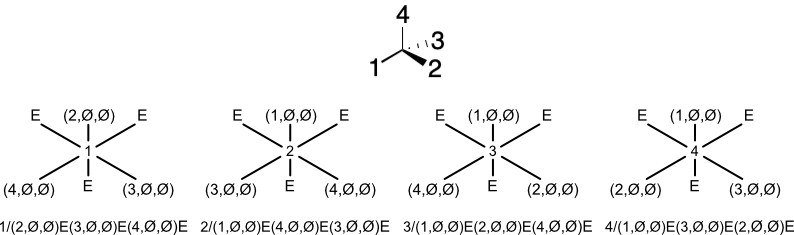

The exact syntax for a projection is unimportant, but might be written as follows. Begin with the order of the prime atom. Concatenate a slash character ("/"). Starting with the position bearing the atom with the lowest order, concatenate the tuple for each position in clockwise order. If a position is empty (i.e., "(Ø,Ø,Ø)"), it can be represented as the uppercase letter "E".

The full stereodescriptor is a concatenation of all possible projections, iterated in increasing prime atom order, and separated by a newline character.

For example, the stereodescriptor for a tetrahedron would start with the complete set of four projections. Iterating them in increasing prime atom order yields the stereodescriptor.

The stereodescriptor for a square planar complex is readily distinguishable from the tetrahedral case. Not only that, but cis and trans forms are distinguishable from each other, without changing the overall process of naming them.

The same can be said for trigonal bipyramidal and octahedral configurations. The approach even works with metallocenes, although a small modification is required.

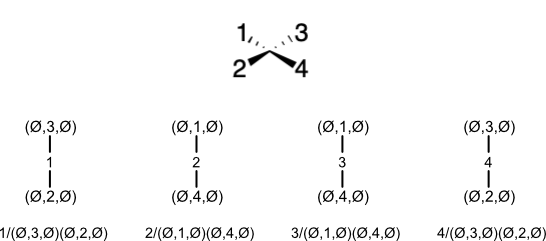

Conformation

Projection can be used to construct stereodescriptors not just for configurational isomers but conformational isomers as well. The bond about which interconversion occurs is chosen as an axis perpendicular to the projection plane. Substituents on each terminal are then projected as before. The approach can be extended to multiple co-linear bonds as in the case of odd cumulenes such as allene.

References

Most of the ideas presented here were adapted from the 1995 paper by Andreas Dietz titled Yet Another Representation of Molecular Structure. In this paper, Dietz approaches the solution in a different way, but arrives at a similar result.

Conclusion

This article describes one approach toward generalized stereodescriptors capable of representing numerous forms of configurational and conformational isomerization using a single abstraction. Some shortcuts were taken in the interest of simplification, but even so the model should be applicable to a wide range of known stereoisomer forms.