Element-to-Atom Mapping in InChI

InChI is a molecular identifier developed by IUPAC. A previous article discussed the possibility of using InChI as something else: a molecular serialization format. Rather than treating InChI strings as mere hash keys, what if InChI could be used to encode and decode molecular structures in the same way as the SMILES or CTfile formats? Doing so requires a way to map elements to their respective atoms. This article describes a way to do that.

InChI as a Molecular Serialization Format

The InChI team has maintained a nuanced stance on the use InChI outside of molecular identification. On the one hand they characterize InChI as just an identifier and not a serialization format. Back in 2014 Steve Heller, co-creator of InChI, noted:

InChI is not a replacement for any existing internal structure representations. (We do not start religious wars. ) InChI is in ADDITION to what one uses internally. Its value to student or scientist is in FINDING and LINKING information.

This sentiment was re-iterated in a 2015 publication which warned "InChI is not a file format (the conversion structure - > InChI - > structure can, in a few cases, provide undesirable results)."

At the same time, the InChI Technical Manual devotes multiple sections to documenting the internal structure of InChI strings: Section III; Section IV; Appendix 2; and Appendix 3. The latter includes instructions for parsing InChI strings and extracting information from their layers.

Although never documented through a formal grammar, InChI strings follow a well-defined syntax. Can this syntax be read, and if so what information might be extracted? The answer to that question depends on a method to map elements to atoms.

Mapping Elements

Tucked away in a 2015 design paper from the InChI team is the following very useful information:

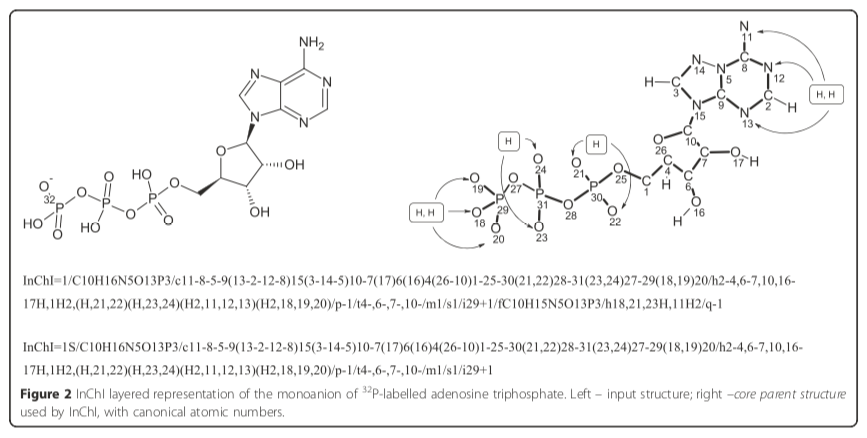

Note that the canonical atomic numbers, which are used throughout the InChI, are always given in the formula’s element order. For example, “/C10H16N5O13P3” (the beginning of InChI for adenosine triphosphate) implies that atoms numbered 1–10 are carbons, 11–15 are nitrogens, 16–28 are oxygens, and 29–31 are phosporus [sic]. Hydrogen atoms are not explicitly numbered.

In other words, elements are assigned to atoms by combining Hill Formula order with atomic indexing. The connections (/c) layer defines a graph whose labels are one-based atomic indexes. To map an element with a given atomic index, begin by creating an array of one-indexed element symbols. Populate this array by reading the Hill Formula from left to right, ignoring hydrogens. Add the appropriate multiple of each element to the array. For example, ATP has a formula layer (/) of "C10H16N5O13P3." The element array therefore contains the following items:

[

C, C, C, C, C, C, C, C, C, C, // 1-10

N, N, N, N, N, // 11-15

O, O, O, O, O, O, O, O, O, O, O, O, O, // 16-28

P, P, P // 29-31

]

Given a random one-based atom index such as 20, the associated element is found by fetching the array element at index 20, which is oxygen ("O"). Figure 2 of the paper illustrates this point for the case of ATP:

The InChI Technical Manual contains additional chemical structures with InChI atomic indexes, all of which are consistent with this assignment procedure.

This procedure is also consistent with the InChI canonicalization algorithm, which is revised in the design paper.

Applications

The reliable construction of a representation that produced an InChI string opens up new applications for the identifier. Every other layer defines its properties in terms of the indexes given in the connection layer. Being able to assign element symbols means that every relevant atomic property can be accounted for.

In other words, it should be possible to go from InChI string to InChI data structure and back to InChI string losslessly.

To what end? At various times over the years, InChI has been used for purposes that don't fit squarely within molecular identification. Examples include:

- Progressive search. The UniChem team disassembled InChI strings to enable progressive compound search that selectively ignored stereochemistry, salt form, or isotopic identity in structure search.

- Similarity search. A team used InChI strings to construct feature vectors, which formed the basis of a similarity search engine.

- Tautomer enumeration. A team in Freiburg based a tautomer enumeration algorithm on InChI.

- Stereoisomer identification. The InChI configuration layer (

/m) was used to identify racemates present in the CCD.

In an application more closely aligned with molecular identification, Noel O'Boyle developed a stereochemistry-aware SMILES canonicalization protocol based on output from InChI software.

InChIs are often associated with an alternative representation such as SMILES or Molfile — but not always. If an InChI string is the only molecular encoding, then a decoder would be an essential component of a text mining system.

Then there's InChI's rather useful ability express molecular structure without introducing mesomer or tautomer artifacts. Applications as diverse as machine learning and chemical registration could benefit.

All of these applications have a common requirement to transform InChI strings into intermediate data structures for further processing. Simpler tasks such as stereoisomer identification can be accomplished with simple string-based data structures. More complex tasks such as tautomer enumeration require something more flexible and precise. A utility for interconverting InChI strings and their corresponding high-fidelity data structures could lead to additional non-identifier applications for InChI.

An InChI Parsing Algorithm

Given the assignment of atomic labels through the formula layer, an algorithm for parsing InChI strings could be summarized as follows:

- Use the connectivity layer (

/c) to build a graph labeled with integer indexes. - Assign atom labels to the nodes on the graph based on the formula layer (

/). - Assign fixed/mobile hydrogens based on the fixed hydrogens (

/h) layer. - Assign stereo and reconnection attributes based on the respective layers.

Key to this algorithm would be a data structure capable of lossless and flexible representation. Ideally, such data structures would discourage or prevent the creation of invalid states.

Caveats

InChI uses a form of molecular representation unlike others in common use such as SMILES or CTfile. In particular, InChI supports tautomerism as a first-class phenomenon through it's "mobile hydrogen" concept. This support has wide-ranging consequences for representation. Additionally, InChI has no concept of bond order. And charges are not associated with a particular atom but rather the molecule as a whole.

Provided that the data structures used for molecular representation take these differences into account, InChI strings could be read and written without loss. However, translation of an InChI representation into another molecular representation runs the risk of mismatch. But this problem is hardly unique to InChI. CTfile V3000 supports enhanced stereochemistry, for example, whereas CTfile V2000 does not. Attempting to translate V3000 molfile to V2000 therefore risks data loss in the same way that translation from InChI does.

Some of these representational differences can be handled in a straightforward way. For example, bond orders can be assigned in the same way that "aromatic" SMILES strings can be kekulized — via matching. Mobile hydrogens can be handled in a similar way. Like kekulization, this generates a single isomer, which may or may not be the desired effect. An old email thread offers additional insights into the InChI translation problem.

Conclusion

The InChI format can be read and written just like other molecular serialization formats. A key factor is the semantic relationship between formula and connectivity layers, which makes element-to-atom mapping possible. This relationship would play a key role in a system capable of lossless interconversion of bare InChI strings and complex data structures. New applications for InChI might then become feasible.