Big Reaction Data

Broad access to chemical information remains a largely unrealized goal. Back in 2006 the second post on this blog noted the recent introduction of PubChem and ZINC as game-changing developments. But despite progress in the creation of open structure collections, repositories linking molecular structure with properties are much less well-developed.

An important frontier in this area is open reaction data. The release of the USPTO reaction dataset added a powerful tool for organic reaction study and application. But beyond this data set lie even larger troves of reaction data, locked away in silos large and small. A new wave of tools like Chematica hints at the kinds of breakthroughs that could become regular occurrences given an open and comprehensive repository of all known reactions.

A Proposal

A recent proposal by Pierre Baldi seeks to consummate chemistry's decades-long flirtation with big data. The idea is as simple as it is ambitious: create and maintain a centralized repository of every known chemical reaction. Both the Large Hadron Collider and the Human Genome Project are cited as inspirations. The effort would be set up as a consortium with the US NIH and NSF at the helm. Five activities would lay the groundwork:

- Seed the repository with the USPTO reaction data set.

- Negotiate permissive licenses to commercial reaction data sets.

- "Crowd-source" the assembly and quality control of reaction data to academic labs and other organizations.

- Develop automated tools for scraping reaction data from the primary literature.

- Legislate the free distribution of reaction data by chemical vendors.

Why Not?

The creation of a comprehensive, open database of all known chemical reactions would mark a transformative moment in chemistry. The proposal offers a way forward, but in my view it only partially addresses or neglects a few major roadblocks. All of them are surmountable given enough resources, but only when recognized as the formidable forces that they are.

First up is constituency, or more precisely the lack thereof. The Baldi proposal would require a substantial (yet unknown) amount of US government funding. That means US Congressional authorization, and more specifically convincing the right lawmakers to support the initiative. Given its long-standing history of lobbying, the American Chemical Society (ACS) might seem like an obvious choice. According to Opensecrets.org, the ACS spent over $200,000 dollars on congressional lobbying in 2021, employing a group of five. But the ACS's dual role as overseer of a multi-million dollar enterprise and a scientific society presents a major conflict of interest. ACS has already proven by its actions a commitment to work against initiatives that threaten its core revenue stream.

Along the same lines, it seems implausible that ACS, Elsevier, and other major players would license their reaction data under the liberal terms needed to support the proposal. Blanket agreements would undermine the business model itself, which is to sell access to a private collection of valuable data to paying customers on an ongoing basis. Baldi notes a recent agreement opening CAS to a data mining group. However, the agreement covered "several million" reactions, whereas CAS itself notes that the collection contains more than "142 million single- and multi-step reactions." This minified approach is consistent with Common Chemistry, which licenses a small subset of the CAS Registry under a Non-Commercial Creative Commons license.

It may yet be possible to convince ACS that its Charter mandate "to increase and diffuse chemical knowledge" overrides financial expediency. But barring a major governance shakeup, the prospect seems remote.

Assuming that government funding for the Baldi proposal could be found, it's not clear exactly what it would buy. The author notes in the conclusion that:

… Substantial care would have to be dedicated to the database’s initial design, kinds of information to be included (reaction conditions, reaction rates, side products, mechanisms, etc.), and mechanisms by which it could be expanded, with or without large-scale crowd sourcing and data curation. …

Scope, limitations, and design matter because mistakes at this level can become technically and politically entrenched, jeopardizing the project's long-term viability. The chemistry community's collective experience with the creation and maintenance of large-scale reaction databases is insignificant compared to that of commercial vendors such as ACS and Elsevier.

Even so, the technical challenges are substantial. In particular, the underlying data representations would require, as Baldi puts it, "substantial care" to get get right. As one example, capturing every reaction requires the ability to accurately represent every molecule. As readers of this blog are well aware, that capability does not yet exist in any industry-standard format. Such limitations can be addressed by either solving the technical challenges directly or narrowing the project scope. Either path risks losing supporters.

The last word, "curation," is a minefield. PubChem accepts compound depositions from the public through a straightforward process. You obtain an account, and for the most part upload whatever you want. Within certain parameters, it does not matter whether the molecule being uploaded has ever been made, or ever can be made. Things get more interesting when synonyms are attached to molecular data. What should be allowed, and how should that information be vetted? My own company has faced this problem with its CAS Number/Molecule interconversion service. The current attitude at PubChem tends toward laissez-faire. The validation burden falls in large part to the users of the database. However, such a stance on a reaction database could render the entire effort useless as speculative or even impossible reactions are deposited, with no scalable way to verify the assertions being made.

Chemistry is different than gene sequencing or building a supercollider in one other way: the space is practically unbounded. Sequencing a genome produces a clear end point. So does building a collider. But no effort to map chemical reaction space will ever be complete. Organic chemistry alone has been in the business of finding surprises for over two centuries. If anything the pace of new reaction discoveries has accelerated. There is no "done" state with an effort like this. And that translates into substantial, hard-to-define, ongoing maintenance and curation costs.

Not only might it be too politically early for a publicly-funded comprehensive and open reaction database, but it might also be too technically early as well.

One more point deserves attention. Although the author notes the essential role played by the small-science academic-led ZINC effort in creating PubChem, he then brushes that aside with the following claim:

… Academic laboratories can be used to nucleate a central database but are not suited to sustain it in the long run as it is not their mission nor do they have the funding, hardware, and software infrastructure to do so. …

The author makes this claim despite the ongoing operation of numerous small-molecule databases run by academic laboratories, either alone or in consortiums. ZINC itself has been in continuous operation since before 2004. Several EU and Asian efforts, though not as long-lived, continue to function while performing ongoing quality-control. Limitations in funding or mandate may exist, but they appear to be surmountable given sufficient alignment of interests.

In zeroing-in on a US government-led coalition, the author also ignores another category of sponsor: the small technology company. e-Molecules, for example, has for many years offered its considerable catalog of small molecules free for download. Some of its peers also do the same, not out of altruism, but out of enlightened self-interest. There could be many as-yet unrecognized common interests between small companies and reaction survey initiatives.

Know Your Customers

Political, technical, and organizational challenges would all require massive efforts, but the proposal doesn't address the most important factor of all: the customers. An effort like the one proposed by Baldi would serve not one, but two distinct groups of customers: consumers and producers. Consumers would use the database in read-only mode. Their use cases are enumerated in the proposal. Producers of reaction data would use the system in write mode, adding new reactions and data on an ongoing basis. They're generally lab chemists who perform reactions on a daily basis. Although the proposal alludes to them in the context of "crowd-sourcing," the picture this paints is far from complete.

What motivates chemists to contribute to a reaction database? The answers will set hard boundaries around the scope and limitations of the system. Here are four classes of incentive that might motivate chemists individually or in groups to contribute to a reaction database:

- Force. Enact laws requiring that certain actions be taken by those who have the means to contribute. Publishers might be compelled to license their data stores under compatible licenses. Chemical suppliers might be forced to deposit reaction data as a condition of commerce.

- Coercion. Threaten negative consequences if the desired actions are not taken. Funding agencies might withhold grants from groups whose chemists do not deposit a set quota of reactions.

- Compensation. Payments of various kinds. Examples might include DOIs to establish priority and leaderboards to increase research visibility.

- Utility. Make the system an essential part of the business of chemistry.

A system built on the first two incentives will not have much of a future. Force not only sends the wrong message, but it's likely to short-circuit many kinds of otherwise productive collaborations. Coercion requires some metric or quota to be satisfied, and that metric is likely to be gamed. If the goal is to capture literally every known reaction as it's discovered, the incentives will need to be much more deeply rooted in the needs of producers.

This is where compensation and utility come in. Keep in mind that I'm speaking from the perspective of data producers, not consumers. Those conducting reactions have many needs around data management, career advancement, and collaboration. A system that fills these needs has the potential to become deeply entrenched and therefore indispensible.

What might such a system look like?

Database vs. Network

Baldi casts his proposal as a database, but I think this unnecessarily restricts the possible solutions. Databases are how information consumers see the world. Information producers see databases as busywork. Self-sustaining systems take both perspectives into account and operate more like a network that brings consumers and producers together. Very successful networks even blur the line between consumers and producers.

It turns out that serving the needs of two different groups of users is extremely difficult. Consumers will only take a network seriously if it has lots of producers. Producers will only care if lots of consumers are present. This sets up a two-sided market and a Catch-22 scenario. Fortunately, a lot has been learned about starting and maintaining two-sided markets over the last fifteen years or so. It seems possible that some of those lessons could be applied to the creation of a universal reaction network to serve the entire chemistry community.

For a glimpse into what this network might look like, consider Chemotion ELN. As described in a 2017 paper, Chemotion meets many of the minimum requirements for a synthetic chemistry ELN that solves real problems faced by chemists on a daily basis. Features include:

- reaction and molecule registration and search

- reagent lookup

- sample tracking

- property calculation

- automatic experimental section production

- analytical instrument integration

- integration with third-party databases

Chemotion can be used as either a hosted service or an open source software package (available from GitHub) that can be installed and run by any lab desiring to do so. Development is active, with the last commit to the GitHub repository having been made less than a month ago.

Chemotion positions itself as a solution for reaction data producers, but buried within it lies a potential solution for the problems faced by reaction data consumers, namely access to high-quality reaction data. In addition to Chemotion's authoring capabilities, the software supports reaction publication features.

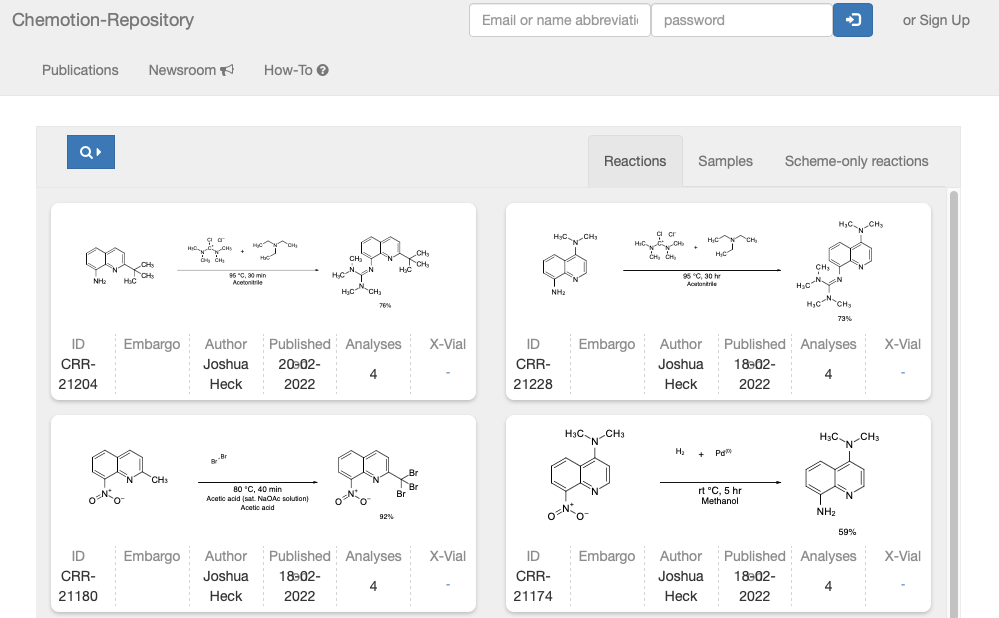

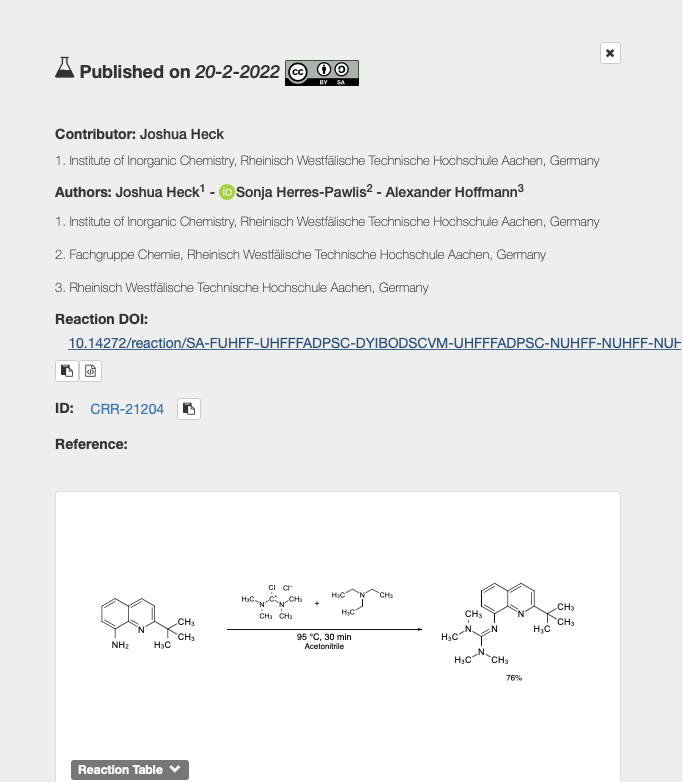

The screenshot above is a view into the Chemotion Repository, a single-reaction publication platform. Chemotion Repository is a separate service from Chemotion ELN, although the two services share a common user interface. Moreover, the two services are integrated in the sense that Repository accepts data imports generated by the ELN. In other words, a chemist can use Chemotion ELN as a daily lab notebook and when the time comes publish to Chemotion Repository with little added effort.

Each reaction has a dedicated page such as this one. The page reads like a mini-publication complete with authors, institutional affiliations, DOI, and graphical abstract. A full experimental procedure follows. Moreover, the page offers something often lacking in the traditional literature, namely complete analytical data including raw 1H, 13C, IR and mass spectral data. We find all of this and a liberal CC-BY license to boot.

To be sure, there are several steps that could be taken to improve Chemotion's utility to data consumers. Some are quite low-hanging fruit. One improvement would be to enable bulk downloads of the kind offered by, for example, PubChem. Another would be to add syndication (RSS, Atom) for automated updates. Yet another would be to add a Web API, essentially a machine-readable version of every publication page.

It's not hard to imagine a system like Chemotion that integrates the functions of ELN, peer-review, and publication into a single network. Such a system would address the needs of both reaction data consumers and producers. In fact, it could blur the lines between consumers and producers in the sense that laboratory work begins to rely on the instant availability of previously-published and vetted procedures. New kinds of collaboration between consumers and producers might become possible, deepening the value and use of the system.

Initiatives like Chemotion have costs, so who funds it? Initial funding was provided by the German government and Karlsruhe Institute of Technology (KIT). More recently, the German Nationale Forschungsdateninfrastruktur (NFDI) has joined. NFDI is an umbrella organization headquartered at KIT with a mission to fund research infrastructure projects in Germany. The chemistry branch NFDI4Chem has taken on a significant financial role in ensuring the continued development of Chemotion, as evidenced by a recent meeting.

Aside from the focus on data capture, what distinguishes Chemotion from the Baldi proposal is scale. Chemotion started as a project whose scope and rollout were small. Over time it has grown to become the core of a much larger consortium effort. In the process, numerous problems have surfaced and been addressed. Others are ongoing and likely to be faced by follower projects. Although a Big Science approach might seem appealing, there are so many problems to work out that funding several smaller efforts may offer a better risk/reward profile.

Conclusion

Wider availability of reaction data is crucial for accelerating the pace of chemical innovation. A recent proposal for a large government-led consortium may seem like an attractive path forward. However, chemistry has little collective experience in this area; both data and administrative know-how tend to occupy silos. Beyond this lies a social and political structure resistant to change. Big Science may not be the best approach. As demonstrated by Chemotion, a case can be made for smaller projects that grow as they succeed.