A Beginner's Guide to Parsing in Rust

Parsers are crucial for many data processing tasks. Contrary to what appearances might imply, writing a parser from scratch is not difficult given the right starting point. This article presents a flexible system for writing custom parsers for a wide range of languages. It assumes some experience with Rust, but no experience with language theory. More experienced readers might want to skip directly to the Lyn crate.

About Parsers

Before diving into practical details, it's important to understand what a parser does. For the purposes of this article, a parser transforms a string into a data structure. A parser can be as simple as a bare function, in which case the problem of writing a parser boils down to implementing that function in a meaningful way.

pub fn parse(string: &str) -> Result<DataStructure, Error> {

todo!("parse string into DataStructure or Error")

}

Many variations on this theme are possible. The important point is that a simple function is a fine starting point for a parser.

Recursive Descent Parsers

The kind of parser described in this article is known as a recursive descent parser. Two things are needed to write such a parser: a formal grammar ("grammar") and a method for reducing it to code.

A grammar is a tool for defining the set of valid strings in a language. This definition usually takes the form of one or more production rules. A production rule represents a single valid transformation allowed under the grammar.

Production rules themselves are expressed using one of a number of possible matasyntax notations. A popular option is Extended Backus–Naur form (EBNF). As an example, consider a language whose valid strings consist of one or more asterisk characters (e.g., *, **, ***, and so on). Let's call it the Star language, which could be defined in EBNF using two production rules:

<string> ::= <unit>+

<unit> ::= "*"

A production rule is composed of two main features: terminals and non-terminals. A terminal is a literal character or character sequence. There is one terminal in the Star language (*). A non-terminal is constructed from terminals and other non-terminals. The name of a non-terminal appears once to the left of an equals operator (::=), and it will usually appear on the right-hand side of one or more production rules. The Star language contains two non-terminals (<string> and <unit>). Quantifiers such as the plus symbol (+, meaning "one or more") are allowed and generally have the same meaning as in regular expression systems. As we'll see, this composition of grammar features lends itself well to translation into many programming languages.

A handy, interactive tool for testing EBNF grammars is BNF Playground. Enter your grammar and an input string, and the Playground will tell you whether the string matches the grammar. The Evaluator will also report syntax errors in the grammar itself.

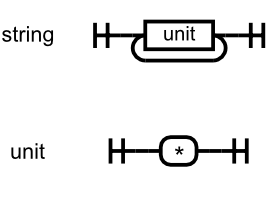

It's not always convenient or desirable to work with formal grammars. Many dialects of "EBNF" are in use, and the differences are great enough to cause issues with tooling. Then there's the problem of communicating syntax to an audience of mixed technical ability. Fortunately, a graphical alternative exists: railroad diagrams. A railroad diagram serves the same purpose as a production rule, but does so graphically. For example, the formal grammar given above can be expressed with the following railroad diagram. Many more examples can be found in the JSON documentation.

Given a grammar, writing a parser boils down to finding a method to translate each production rule into a function. It's convenient to name these functions after the production rules they express. The parser for the Star language would have two functions named string and unit, respectively. By translating syntax features into programming language control statements, we can arrive at a method to translate the Star grammar into a validating parser.

pub fn string(string: &str) -> bool {

let mut state = State {

cursor: 0,

characters: string.chars().collect::<Vec<_>>()

};

loop {

if !unit(&mut state) {

break

}

}

state.cursor > 0 && state.cursor == state.characters.len()

}

fn unit(state: &mut State) -> bool {

match state.characters.get(state.cursor) {

Some(character) => if character == &'*' {

state.cursor += 1;

true

} else {

false

},

None => false

}

}

struct State {

cursor: usize,

characters: Vec<char>

}

To test whether a str encodes a member of the Star language, we call the string function. A return value of true indicates membership. Notice that Rust's Boolean type serves as the data structure returned from this parser. This return value can be as simple or complex as you'd like.

Grammar and method are connected. Although the topic is too involved for this post, I discuss it in Scanner-Driven Parser Development. To recap the most important point, writing a recursive descent parser requires a grammar without left recursion. Consider the infinite recursion problem involved with translating the following grammar into functions:

<string> ::= <string> <unit>

<unit> ::= "*"

Fortunately, such grammars can usually be refactored to eliminate left recursion.

Scanner

The sample parser for the Star language uses a State instance to keep track of internal state. This is common for function-based parsers. As the example illustrates, it quickly becomes clumsy to burden individual functions with updating the parse state. A better approach is to move that responsibility into the type itself. The result is a scanner.

The State type can be transformed into a Scanner with the addition of some simple methods for accessing and mutating state:

pub struct Scanner {

cursor: usize,

characters: Vec<char>,

}

impl Scanner {

pub fn new(string: &str) -> Self {

Self {

cursor: 0,

characters: string.chars().collect(),

}

}

/// Returns the current cursor. Useful for reporting errors.

pub fn cursor(&self) -> usize {

self.cursor

}

/// Returns the next character without advancing the cursor.

/// AKA "lookahead"

pub fn peek(&self) -> Option<&char> {

self.characters.get(self.cursor)

}

/// Returns true if further progress is not possible.

pub fn is_done(&self) -> bool {

self.cursor == self.characters.len()

}

/// Returns the next character (if available) and advances the cursor.

pub fn pop(&mut self) -> Option<&char> {

match self.characters.get(self.cursor) {

Some(character) => {

self.cursor += 1;

Some(character)

}

None => None,

}

}

}

Now it's possible to refactor string as follows.

pub fn string(string: &str) -> bool {

let mut scanner = Scanner::new(string);

loop {

if !unit(&mut scanner) {

break

}

}

scanner.cursor() > 0 && state.is_done()

}

fn unit(scanner: &mut Scanner) -> bool {

match scanner.peek() {

Some(character) => if character == &'*' {

scanner.pop();

true

} else {

false

},

None => false

}

}

Room for Improvement

Although tucking state manipulation into Scanner cleans things up a bit, it doesn't noticeably affect the structure of the parser code itself. The problem is that the current Scanner API forces mutators and accessors to be applied in separate operations. Given a complex language with many production rules, exposing all of the gruntwork can hide the actual purpose of parser functions. Even worse is the potential for introducing bugs. It's easy to forget to call pop after peek. And the peek/pop sequence is ubiquitous in recursive descent parsers.

What if it were possible to eliminate these problems?

The take Method

The unit function could be re-written to use a new Scanner method called take. It accepts a character to be compared at the current cursor position. If found, the cursor is advanced and true is returned. Otherwise, false is returned.

fn unit(scanner: &mut Scanner) -> bool {

scanner.take(&'*')

}

The take method could in turn be implemented by merging the code that would otherwise have been present in the unit function (and similar functions using the peek/pop pattern).

/// Returns true if the `target` is found at the current cursor position,

/// and advances the cursor.

/// Otherwise, returns false leaving the cursor unchanged.

pub fn take(&mut self, target: &char) -> bool {

match self.characters.get(self.cursor) {

Some(character) => {

if target == character {

self.cursor += 1;

true

} else {

false

}

}

None => false,

}

}

The transform Method

Sometimes a parser requires a 1:1 transformation of a character into some data structure. This pattern can be especially tedious with the peek/pop pattern. Consider a language in which certain symbols translate to an unsigned integer value.

<value> ::= "$" | "#"

The parser would look something like this using peek/pop:

fn value(scanner: &mut Scanner) -> Option<u8> {

match scanner.peek() {

'$' => {

scanner.pop();

Some(1)

},

'#' => {

scanner.pop();

Some(2)

},

_ => None

}

}

The value function could be re-arranged in various ways. But none of them would address the root problem, which is that we want to use a single match statement without littering calls to pop in every branch.

A solution is the transform method, which accepts a callback and returns an optional value.

fn value(scanner: &mut Scanner) -> Option<u8> {

scanner.transform(|character| match character {

'$' => Some(1),

'#' => Some(2),

_ => None

})

}

Not only is the intent of this code much clearer, but it is also much less error prone. It is also potentially more performant than some alternatives.

The transform method, like the take method, can be implemented by merging the code that would otherwise appear in the parser.

/// Invoke `cb` once. If the result is not `None`, return it and advance

/// the cursor. Otherwise, return None and leave the cursor unchanged.

pub fn transform<T>(

&mut self,

cb: impl FnOnce(&char) -> Option<T>,

) -> Option<T> {

match self.characters.get(self.cursor) {

Some(input) => match cb(input) {

Some(output) => {

self.cursor += 1;

Some(output)

},

None => None

},

None => None

}

}

The scan Method

Similar refactorings can be used whenever the appearance of parser function diverges noticeably from its corresponding production rule. Consider the following grammar, which might be used to parse the chemical elements into the appropriate variant of the enum Element.

<element> ::= "A" "c" | "B" "r"?

The implementation might look something like this.

pub enum Element {

Ac,

B,

Br,

// ...

}

pub enum Error {

Character(usize)

}

pub fn element(scanner: &mut Scanner) -> Result<Option<Element>, Error> {

match scanner.peek() {

Some('A') => {

scanner.pop();

match scanner.peek() {

Some('c') => {

scanner.pop();

Ok(Some(Element::Br))

},

_ => Err(Error::Character(scanner.cursor()))

}

},

Some('B') => {

scanner.pop();

match scanner.peek() {

Some('r') => {

scanner.pop();

Element::C

},

_ => Element::C

}

},

_ => Ok(None)

}

}

As before, there are several tricks for cleaning this up. The problem is that none of them can address the root problem. We want to write a single match statement that transforms all 100+ two-letter element symbols into its corresponding enum variant — without introducing more characters of lookahead or nested match arms.

This problem too can be solved by introducing a new Scanner method, scan. Like transform, scan accepts a closure returning a value that will determine further actions taken. Unlike transform, however, scan is repeatedly called until an exit condition is detected. This makes it possible to transform multi-character sequences with fine precision.

pub fn element(scanner: &mut Scanner) -> Result<Option<Element>, Error> {

scanner.scan(|symbol| match symbol {

"A" => Some(Action::Require),

"B" => Some(Action::Request(Element::B)),

"Br" => Some(Action::Return(Element::Br)),

_ => None

})

}

The scan method, like take and transform, was built by factoring out the code that would have otherwise been contained within parser functions.

pub enum Action<T> {

/// If next iteration returns None, return T without advancing

/// the cursor.

Request(T),

/// If the next iteration returns None, return None without advancing

/// the cursor.

Require,

/// Immediately advance the cursor and return T.

Return(T)

}

pub fn scan<T>(&mut self, cb: impl Fn(&str) -> Option<Action<T>>) -> Result<Option<T>, Error> {

let mut sequence = String::new();

let mut require = false;

let mut request = None;

loop {

match self.characters.get(self.cursor) {

Some(target) => {

sequence.push(*target);

match cb(&sequence) {

Some(Action::Return(result)) => {

self.cursor += 1;

break Ok(Some(result))

},

Some(Action::Request(result)) => {

self.cursor += 1;

require = false;

request = Some(result);

},

Some(Action::Require) => {

self.cursor += 1;

require = true;

},

None => if require {

break Err(Error::Character(self.cursor))

} else {

break Ok(request)

},

}

},

None => if require {

break Err(Error::EndOfLine)

} else {

break Ok(request)

}

}

}

}

Lyn Crate

Scanner can conveniently be used via the Lyn crate. It will be incorporated into the reference implementation for a molecular language I'm working on. If you use Lyn in a project I'd be very interested in hearing from you.

About Parser Generators

As an alternative to writing a recursive descent parser, it's also possible to build a parser directly from a grammar using a parser generator. Many sources give the impression that a parser generator is the only way to parse. Having used a few parser generators, I don't necessarily agree. Some of the downsides of a parser generator include:

- Awkward code management. A parser generation will often emit source code that must somehow be integrated within a source tree. But being auto-generated, this code can't be managed with any of the usual workflows.

- Confusing stack traces. The flow through auto-generated code can be confusing to follow. This makes debugging more difficult than it otherwise might be.

- Some parser generators require learning unfamiliar and/or poorly-supported APIs. These are furthermore sometimes specific to a single programming language. So the investment made in them can't necessarily move on when you do.

Although parser generators can save effort in the short term, the full extent of the disadvantages often won't become known until some time in the future of a project. For this reason, I recommend trying to write a recursive descent parser or two first, and only then moving on to a parser generator when the advantages of doing so will clearly outweigh the disadvantages.

Conclusion

Recursive descent parsers are straightforward to write given a solid starting point. This article has to painted a picture of what this starting point might look like. Two tools are required: a grammar; and a method for turning its production rules into functions. A scanner is a powerful tool for the latter, allowing the resulting functions of a parser to closely resemble the corresponding production rule. A scanner can be as simple or complex as your language requires. Three examples demonstrated how to move repetitive, bug-prone code into the scanner for cleaner, simpler parsers. The Lyn crate offers a fully-functional scanner.

Acknowledgement

Peter Malmgren's article Implementing a calculator parser in Rust helped crystallize some of my ideas about explaining recursive descent parsers.