Typed JavaScript

In JavaScript, all type errors are reported at run time. The main benefit is a syntax that's easy to learn and use, but it comes at a cost. As a project grows and matures, the convenience of dynamic typing can give way to frustration with code quality and maintainability. This article introduces a low-friction solution, Typed JavaScript.

In a Nutshell

Typed Javascript is a system of tools and practices that expose type errors before run time. Unlike other options, Typed JavaScript runs without modification wherever JavaScript runs. Typed JavaScript offers static type checking, without compilers or unusual tooling. You can use as much or as little Typed JavaScript as you like. If things don't work out, changes are easy to revert.

To get an idea for how Typed JavaScript works, consider a function that adds two numbers.

const add = (i, j) => {

return i + j;

};

Although the intent of add is numerical addition, JavaScript will unconditionally accept arguments of any type for the parameters i and j. What happens if the first argument is a string instead of a number? We won't get an error, but we probably won't get what we're after, either.

console.log(add(4, 2)) // => 6

console.log(add('4', 2)) // => '42'

It's easy to catch the error by inspection in this simple example because both arguments are literals and the implementation of add is a single line. But in complex JavaScript projects, arguments and return value may be separated by several function calls. This distance in time and space can make debugging very difficult.

Even if a type error can be traced, preventing its recurrence is hardly straightforward. To stamp out all possible type errors, we could add guard code as in the following example. Even so, the best we'd get is run time notification of an error. The user would still face the full consequences of that error.

const addWithCheck = (i, j) => {

if (typeof i !== 'number' || typeof j !== 'number') {

throw new Error('arguments must be numbers');

}

return i + j;

};

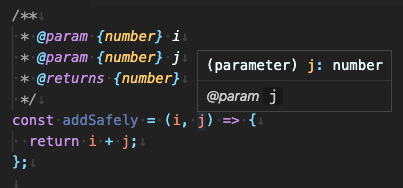

Typed JavaScript solves this problem through type annotations (aka "type hints"). A type annotation constrains the range of types a given value may assume. Typed JavaScript's annotations are implemented through tagged JSDoc comments. For example, The range of allowed inputs and outputs for the add function can be constrained like so.

/**

* @param {number} i

* @param {number} j

* @returns {number}

*/

const addSafely = (i, j) => {

return i + j;

};

Given the right tooling, type errors involving the addSafely function will become visible as you write. Visual Studio Code, for example, supports interactive type checking out of the box. As a bonus, intellisense will report type information through mouse hovers and autocompletion.

Benefits

Typed JavaScript offers a powerful suite of tools for constraining the allowed types a value may assume. But using this system is not without costs. It takes time and attention to develop good types. What's the payoff?

As the previous section mentioned, one win is code quality. A 2017 study looked at the prevalence of type-related bugs in public JavaScript repositories. It found that type checking prior to run time would have prevented at least 15% of reported bugs.

A less tangible but perhaps more important factor relates to design. Many years ago Linus Torvalds made this statement about code and data structures:

In fact, I'm a huge proponent of designing your code around the data, rather than the other way around, and I think it's one of the reasons git has been fairly successful. … I will, in fact, claim that the difference between a bad programmer and a good one is whether he considers his code or his data structures more important. Bad programmers worry about the code. Good programmers worry about data structures and their relationships.

Torvalds wrote this while discussing Git. He pointed to the stability of the data structures used there. Stable and well-documented data structures offer a firm foundation on which to build software.

Writing in The Mythical Man Month, Fred Brooks famously put the idea this way:

Show me your flowcharts and conceal your tables, and I shall continue to be mystified. Show me your tables, and I won’t usually need your flowcharts; they’ll be obvious.

JavaScript's lack of developer tooling around types tends to produce software focused on code, with data structures taking a back seat. Typed JavaScript layers a capable type system on top of JavaScript. Developers get a language and tooling for thinking about, designing, documenting, discussing, and using data structures. I've used Typed JavaScript for a while now and have experienced its pronounced ability to shift focus to data structures early in the design process.

Documentation is another benefit of Typed JavaScript, and it comes at no added cost. JSDoc3 transforms a repository of Typed JavaScript into HTML documentation. The result is ready to publish.

Nothing New

If Typed JavaScript looks like something you've seen before, you're probably right. Typed JavaScript is a name I made up to describe practices, conventions, and tooling that has been in place for some time. The previous lack of a name has made Typed JavaScript difficult to learn about, use to maximum effect, and advance. I'm hoping that a searchable label under which to organize currently fragmented information will lead to more productive use and faster evolution of statically typed JavaScript. I'm taking the first steps in that direction myself with the articles in this series.

Foundations

Typed JavaScript's type system traces its origins to one contained within the now abandoned ES4 proposal. Closure Tools later implemented a related type system using an approach very similar to Typed JavaScript, but without IDE tooling. Years later, Microsoft made its own changes to bring this type system in line with the TypeScript type system, adding VS Code support along the way. Typed JavaScript is based on the grammar and syntax of the Microsoft system.

Underlying Typed JavaScript's type system is a set of primitives, including: undefined; null; boolean; number; string; object; array; and function. These primitives can be composed into complex user-defined types. Although some documentation on this type system exists, it is scattered among a number of sources and is incomplete.

A future article will discuss the syntax and semantics of the Typed JavaScript type system in detail. For a preview, see the preceding article in this series, Types without TypeScript. For now, just a few illustrative examples will be given.

As noted previously, type definitions are encoded into JDoc comments using tags beginning with the at (@) character. The types of function parameters, return values, and variables can all be constrained using these tags.

/**

* @param {string} a

* @returns {number?}

*/

const convert = (a) => {

const result = parseFloat(a);

if (isNaN(a)) {

return null;

} else {

return a;

}

};

// ERROR

convert(42);

/** @type {string|undefined} */

let foo = undefined;

// ERROR

foo = 42;

In the first example above, convert indicates that it will return either a number or null with the trailing question mark (?) character. Treating the return value as any other type results in an error, just like passing a value of any type other than string results in an error. The second example uses the same convention to constrain the type of a variable to string or undefined. Assigning a value of type number yields an error.

Typed JavaScript is especially useful for function functions accepting complex parameters types. In the example below, a type error will be generated if an object lacking a grade property of type number is passed to averageGrade.

/**

* @typedef {object} Student

* @property {number} grade

*

* @param {Array<Student>} students

* @returns {number}

*/

const averageGrade = students => {

return students

.reduce((total, student) => total + student.grade, 0) / students.length;

};

// ERROR

averageGrade([ { } ]);

Using Typed JavaScript

As mentioned previously, VS Code supports Typed JavaScript out of the box. The easiest way to get started with Typed JavaScript and VS Code is to place a single line of text at the top of a JavaScript file, like so:

//@ts-check

// VS Code now reports Typed Javascript types and type errors

Although adding a comment to every JavaScript source file might not seem like a problem, it does add clutter and doesn't allow for much customization. A better approach is to add a tsconfig.json file to the top-level of a JavaScript project. tsconfig.json is a file typically used with a TypeScript project. However, adding the compiler options compileJs and checkJs activates type checking for JavaScript projects as well. The following tsconfig.json will check types in the lib directory of a Node.js project while excluding the node_modules directory.

{

"compilerOptions": {

"outDir": "./dummy",

"target": "ES6",

"lib": ["ES6"],

"checkJs": true,

"allowJs": true,

"skipLibCheck": true,

"moduleResolution": "node",

"strictNullChecks": true,

"allowSyntheticDefaultImports": true

},

"exclude": [

"node_modules"

],

"include": [

"lib/**/*.js"

]

}

Just adding a tsconfig.json file will be a step forward, but you may be alarmed to discover that VS Code only checks types for open files. If your edits to an opened file introduce errors into closed files, these errors will only be seen when the closed files are opened. This renders many of the benefits of Typed JavaScript moot. This problem arises from a longstanding issue in VS Code and does not appear to be any closer to resolution now than it was in 2018.

Fortunately, the following workaround solves the problem. Create a tsc task by adding a file with the following content to .vscode/tasks.json.

{

"version": "2.0.0",

"tasks": [

{

"label": "tsc",

"type": "shell",

"command": "./node_modules/typescript/bin/tsc",

"presentation": {

"echo": true,

"reveal": "never",

"focus": false,

"panel": "shared",

"showReuseMessage": true,

"clear": false

},

"args": ["--noEmit", "--watch"],

"problemMatcher": [

"$tsc-watch"

],

"isBackground": true

}

]

}

This task will run, but will not work correctly. To get it working, install the typescript package:

npm i typescript -D

With this dependency in place, type checks can be reported for closed files. Select the "Run Task" option from the "Terminal" menu. Then type "tsc" and press return. Now type errors will be reported regardless of whether the file containing them is open or not.

Detachable Types

Typed JavaScript is a kind of detachable type system. A detachable type system augments a language with optional types using a loosely-coupled syntax. In Typed JavaScript, loose coupling is achieved with tagged comments. This results in type annotations that can be added and removed with minimal effect on the underlying code, and without fracturing the language itself.

Alternatives

Two alternatives to Typed JavaScript are available: Typescript and Flow. Both approach the problem of types in JavaScript by introducing a compiler and custom syntax. Both share the same goal as Typed Javascript, namely, to add type safety to JavaScript. However, Flow and Typescript are distinct languages. Neither can be executed on a browser or by Node.js. The mandatory compile step makes Flow and TypeScript more difficult to use in certain situations than Typed JavaScript.

Conclusion

Typed JavaScript is a detachable type system that brings static type checking to JavaScript. In contrast to alternatives like Typescript and Flow, Typed JavaScript requires no compile step and yet is supported out of the box by popular tools like VS Code. If you like the idea of static type checking and want to continue using JavaScript, Typed JavaScript is worth considering. A future article will discuss Typed JavaScript's type system in detail.