Molecular Assembly Index

How can life be recognized as such? The question has great scientific, technological, and cultural importance. One school of thought says that we should start with a definition. But after 123 attempts and counting, just defining the word "life" has yielded more heat than light. This article discusses a paper that takes an entirely different, cheminformatics-driven approach to the question of detecting life as we do and don't know it.

Molecular Evidence for Life

Rather than trying to define what life is, why not focus instead on what life does? This question underpins a new paper from the Cronin Group. It proposes a new method for recognizing present and past life through a mathematically-grounded analysis of the molecular evidence life leaves behind. The video below offers a general audience background to the idea.

What kinds of molecules does life produce? We need to check our assumptions here. Life on Earth appears to based on a single chemical repertoire. But it would be a mistake to extrapolate this narrow observation to the ancient Earth, other planets, or even a laboratory. Life's operating systems may be more numerous and bizarre than we can imagine.

What's needed is a general-purpose biosignature - molecular evidence for past or present life. But this biosignature must not be biased toward any single variety of biochemistry. Instead, it should be based on math, providing a numerical readout from which life's presence can be objectively inferred regardless of what form it takes or what kind of chemistry is involved.

Molecular Assembly

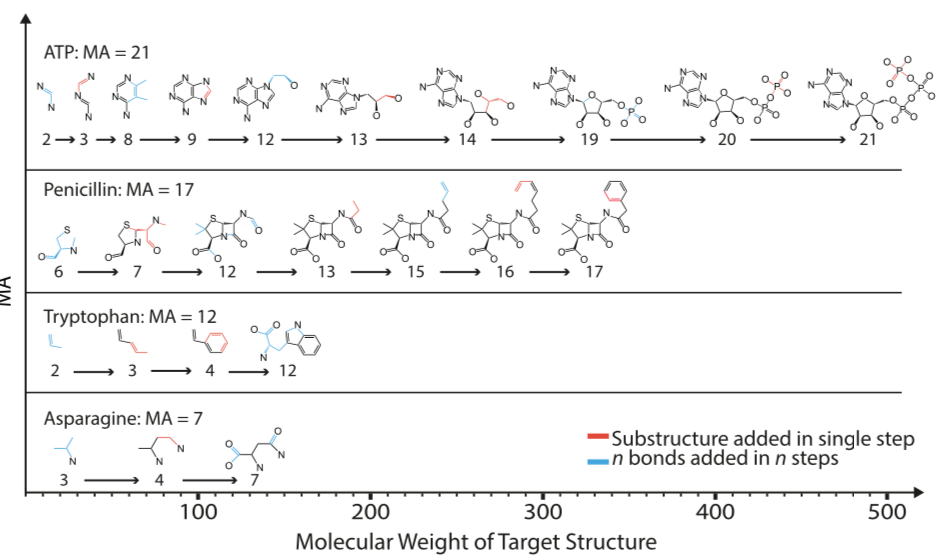

The paper proposes a method for life detection based on molecular assembly index (MA). Confusingly, the same paper also uses the term molecular assembly number. As far as I can tell, both terms refer to exactly the same thing. For the rest of this article, I'll use the abbreviation "MA" to to refer to either molecular assembly number or molecular assembly index.

The idea behind MA is straightforward in principle. Break a target molecule into its unique, irreducible pieces, then assemble the pieces recursively. The minimum number of iterations required to reassemble a molecule is its MA. Put another way, MA is the number of steps in a molecule's shortest assembly sequence. As such, MA is a positive integer that should be positively correlated with molecular complexity.

Simple though MA may be in concept, things get complicated very quickly. The paper presents two distinct varieties of MA, although this may not be immediately obvious:

- Pathway MA. The closest fit to the process described above and in the paper's text and figures. Break the molecule up into indivisible pieces, then report the length of the shortest path to assemble them back into the target molecule after an exhaustive search.

- Split-branch MA. An upper bound on pathway MA. Whereas pathway MA is computed from the set of bonds, working up to the target molecule, split-branch MA works by dividing the target molecule into ever smaller fragments. Split-branch MA is reported to be more computationally tractable than pathway MA. For this reason, the SI, downloadable binary executable, and experimental results are all based on split-branch MA, not pathway MA.

The paper's conceptual description of MA refers to pathway MA, but all experimental work, flowcharts, and C++ software implementations rely on split-branch MA.

Understanding MA requires a detailed understanding of pathway MA, but that description has not been published. The following section fills in some of the gaps based on my reading of the published literature. It's entirely possible I've gotten some things wrong here, and corrections are welcome.

A Pathway MA Algorithm

A pathway MA algorithm can be devised that accepts a molecular graph (target) as input, and returns a positive integer representing the corresponding pathway MA. The result is obtained through recursive, random recombination of input's unique bonds. Each round builds ever more complex subgraphs of target until target itself emerges. The sequence of steps that generates target is called an "assembly pathway." A given molecule can have many pathways of identical or different lengths. The minimum assembly pathway length is the pathway MA.

function compute_ma

input: Molecule target

output: int

let soup = fragment(target)

return enrich(soup, target, 0)

function fragment

input: Molecule target

output: Set<Molecule>

let result = new Set()

for bond in target

// Bond -> Molecule

let graph = molecule_for_bond(bond)

insert(result, graph)

return result

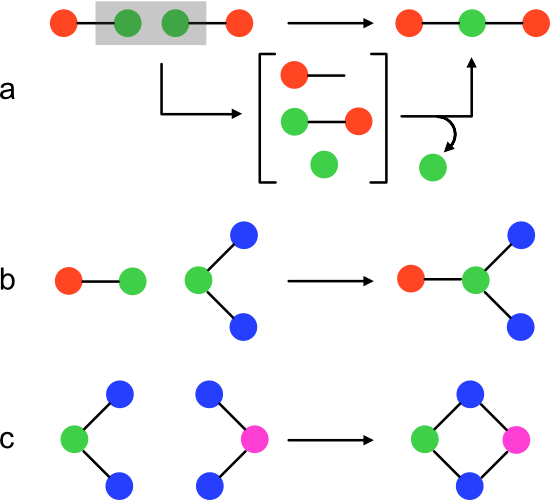

At the highest level, the algorithm performs two steps (function compute_ma). First, the target is fragmented into a set of unique two-atom, one bond subgraphs. These are target's unique bonds, but cast as Molecules. Next, the fragments are recombined with the recursive function enrich.

The pathway MA algorithm's central abstraction is soup, a subset of target subgraphs. Initially, soup contains the unique bonds in target. Each enrichment iteration adds one target subgraph until either target itself is produced or it becomes impossible to obtain target from soup.

function enrich

input: Set<Molecule> soup

Molecule target

int index

output: int

let indexes = new Set()

for left in soup

for right in soup

for product in assemble(left, right)

if is_isomorph(product, target)

return index

else if size(product) < size(target)

let next_soup = clone(soup)

let next_index = enrich(next_soup, target, index + 1)

if next_index > 0

insert(indexes, next_index)

// -> -1 if indexes is empty

return min(indexes)

Enrichment of soup occurs through the enrich function. It accepts soup, target, and an integer (index) as arguments. The return value is either the MA of target, or -1 if none was found.

During an enrichment iteration, products are generated for each pair of soup members. If a product is isomorphic with the target, index is returned as the MA. A product of size (edge count) greater than target can't lie on its assembly pathway because each step increases the edge count. Therefore, a product is added to the soup only if its size is less than target. Otherwise, the product is ignored. The enrich function can be thought of as performing an exhaustive traversal over the assembly space of a molecular graph.

function assemble

input: Molecule left

Molecule right

output: Set<Molecule>

let result = new Set()

for left_atom in left

let global = merge(left, right)

for right_atom in right

if !joinable(left_atom, right_atom)

continue

let local = merge(left, right)

join(local, left_atom, right_atom)

join(global, left_atom, right_atom)

insert(result, local)

insert(result, global)

return set

Product formation is controlled through a process I'll call assembly (function assemble). Assembly returns a set of Molecule products given two members of the soup (left and right). To create a product, left and right are first merged into a two-component graph. The set of all possible combinations of new bonds between left and right is then exhaustively installed to yield products.

function condense

input: Molecule molecule

Atom left

Atom right

output: Molecule

for bond in molecule

replace(bond, left, right)

remove(molecule, left)

New bonds are made through a process I'll call condensation (function condense). condense accepts a two-component Molecule and one atom from each component as input. The function updates each bond pointing to the first atom such that it will point to the second atom instead. Finally, the first atom is removed from the molecule.

The authors don't state how much more efficient it is to compute split-branch MA rather than pathway MA, but suggest that computational cost was one factor that motivated the development of the the former:

… Computing an assembly pathway of a molecule can be done simply by decomposing the object into fragments and reconstructing it, however, identifying the shortest pathway is computationally challenging.

MA as a Biosignature

The process of computing assembly MA is modeled after abiogenesis, the natural process whereby non-living matter gives rise to life. The algorithm's growing set of molecular fragments (the soup) recalls the notion of a primordial soup in which ever more complex molecules arise from simpler ones through random events. As chemical systems capable of evolution arise, certain pathways become amplified well beyond the expected background level. As the authors note:

… Our central thesis is that molecules with high MA are very unlikely to form abiotically, and the probability of abiotic formation goes down as MA increases, and hence experimental determination of MA is a good candidate for a life detection system. If our hypothesis is correct, then life detection experiments based on MA can indicate the presence of living systems, irrespective of their elemental composition, assuming those living systems are based on molecules.

Testing this hypothesis, however, requires a method for linking an observable quantity with MA.

Linking Assembly Theory with Experiment

Given the time scales likely to be involved, direct observation of abiogenesis may not be feasible. However, the problem becomes more tractable when considered from the opposite direction. What can molecular disassembly reveal about the pathway that produces a molecule?

Tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) offers a powerful, well-established tool to for molecular disassembly. MS/MS is especially useful because it requires no prior purification of samples. Complex mixtures, sampled directly from the environment, can be used. Individual molecular species can then be selected and fragmented. The fragments can then be characterized by mass.

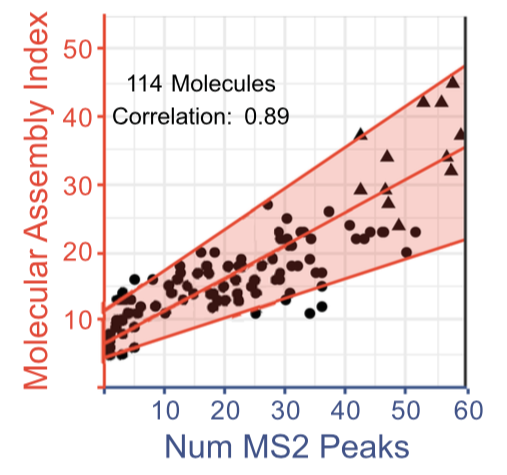

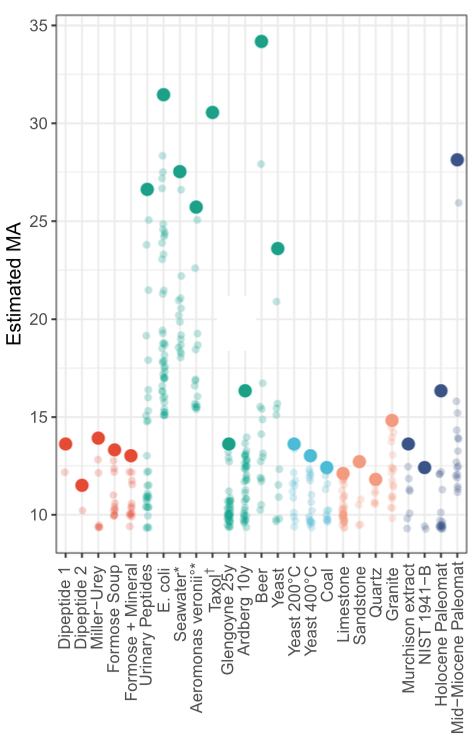

The authors speculated that the MS2 peak count for a particular ion would be positively correlated with its split-branch MA. This was found to be the case.

In an experiment designed to model a a biosignature search, a variety of mixtures were fragmented, the MS2 peak count obtained from the strongest MS1 peak was determined, and the implied MA was computed. The data show clear patterns among samples labeled as abiotic; dead; inorganic; and biological. These results imply an MA threshold for "living samples" of about 15. The estimate is not without caveats, but does avoid many of the problems faced by alternative techniques.

It's not clear when an MA-based life detection experiment might be deployed aboard a robotic spacecraft. The authors note that the specific MS/MS instrument used "has a much higher resolution than mass spectrometers expected on planned space missions, and our goal here is to demonstrate the viability of this analysis in principle."

Broader Implications

MA may find applications beyond Origins of Life research. For example, MA defines a potential scale for molecular complexity. As such, it joins a body of work extending back to at least 1955. A recent paper reviewed known approaches to measuring molecular complexity, grouping them into two categories:

- Identify substructure-related features and their probability of occurrence to derive Shannon entropy.

- Use an expert-formulated weighting system to tally the contribution of various predefined substructures.

MA and and its spinoffs may represent a third category of complexity scale.

Applications for molecular complexity scales can be found throughout chemistry and biology. A 2018 review focused on applications in drug discovery.

Conclusion

MA is a new molecular descriptor designed and experimentally validated for biosignature detection. Two versions of MA were reported, pathway MA and split-branch MA. The former matches the authors' explanation of the index, but only the latter was documented in detail and reduced to software. To fill the gap, this article condenses the published literature to arrive at an algorithm for computing pathway MA. As a new kind of unbiased complexity metric, MA may find application in diverse areas of chemistry.

Summary image credit: Wikipedia