Matched Molecular Pairs

Early-phase medicinal chemistry is full of challenges and uncertainties. But despite it all, the entire enterprise can often be boiled down to just one question: which compounds should be tested next?

Opinions differ on the role that cheminformatics should play here. One school of thought says to simply supply the answer. Recent advances in machine learning have bolstered this view. Another line of thinking says that cheminformatics should equip the medicinal chemist with the tools to choose the next compound to be tested. This article discusses a practical algorithm aligned with the latter view.

What to Test Next

Quantitative structure activity (QSAR) models can be useful, but are often opaque. Given high compound attrition rates, what's needed most often is not active and selective compounds but instead a blueprint for making active and selective compounds. A model formulated in the language of medicinal chemistry is an effective way to achieve this.

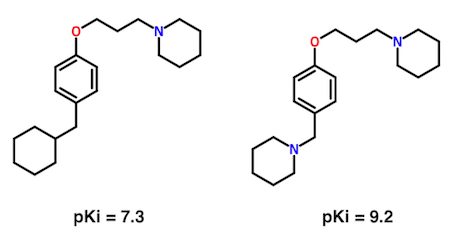

A key element of this language is the pairwise comparison of closely-related chemical structures and associated properties. Consider the following pairwise comparison from one of my drug discovery projects.

What's most important about the pair is not the sub-nanomolar binding affinity of the compound on the right. Rather, it's the indication that a second basic nitrogen atom increases affinity by nearly 100-fold. From this single observation, a hypothesis which ultimately lead to hundreds of new, active compounds was formulated.

A pairwise relationship may be observed to be additive with respect to each other. If so, the effect of a pairwise structural change can be added to the effect of another pairwise structural change. Deviations from additivity suggest a change in binding mode. Using these simple conceptual tools, quantitative models grounded in the language of medicinal chemistry can be developed.

How closely should two compounds in a pairwise relationship resemble each other? Consider the purpose of the comparison, which is to generate hypotheses. The compounds must be similar enough in structure to suggest a clearly-defined hypothesis. Testing the hypothesis requires a practical method to access both members of the pair, which favors single bond disconnections.

Matched Molecular Pairs

The well-known medicinal chemistry practice of pairwise structural comparison has been formalized as Matched Molecular Pair (MMP) analysis. One definition calls an MMP a pair of molecules "that differ only by a particular, well-defined, structural transformation." Often a measured property of some kind is associated with each member of the pair.

The main value of MMPs lies not in their generation, which is straightforward and can be done manually. Rather, the value lies in extracting MMPs from large collections of existing structure-activity relationships (SARs). Such work is repetitive and error-prone - just the sort of problem computers were created to solve.

But this raises the question: how can MMPs be identified algorithmically within large data sets?

The Hussain-Rea Algorithm

Two broad categories of MMP-finding algorithms have been developed over the last few decades: supervised and unsupervised. A supervised algorithm relies on one or more precompiled templates to identify pairs. An unsupervised algorithm can identify MMPs without precompiled templates. Until 2010, most published MMP algorithms were supervised. The ones that were not relied on maximum common subgraph (MCS) analysis, an expensive proposition for large data sets.

In 2010, Hussain and Rea reported the first efficient, unsupervised MMP algorithm. An implementation was shown to effectively extract MMPs from large data sets with modest hardware requirements.

Rather than jumping directly into the algorithm as the paper does, I think it's more instructive to describe the central operation in some detail.

Making the Cut

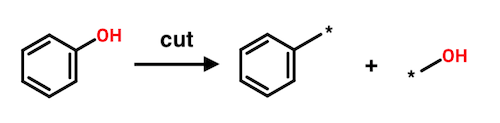

The Hussain-Rea algorithm is based on an operation called a cut. A cut removes an acyclic bond of order one between two heavy atoms in a connected molecular graph. Because the bond that is removed is not part of a ring, two fragments must result. A cut can be reversed by fusing the fragments through the bond that was previously cut.

Each fragment resulting from a cut can be considered the substituent of its mate. In the above example, the benzene ring can be viewed as a substituent of hydroxyl. Likewise, hydroxyl can be viewed as a substituent of benzene. This symmetry plays a prominent role in the Hussain-Rea algorithm.

As will soon become clear, it's useful to designate one of the fragments resulting from a cut as the core. A core is a fragment to which one or more fragments are attached. In the case of a single cut, only two fragments are generated and so each can be designated as a core, depending on perspective. Consider again the example of phenol. Either benzyl or hydroxyl could be considered to be the core fragment. The authors tend to refer to the complementary (non-core) fragment as just a "fragment."

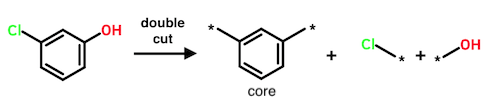

Performing two cuts yields three fragments, one of which necessarily connects to both of its mates when the cuts are reversed. This central fragment is always designated as the core.

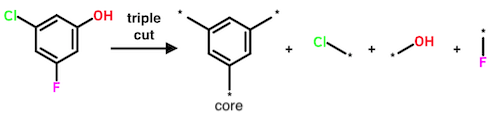

Performing three cuts yields four fragments. Here there are two possible modes: (1) the third cut is made inside the core; or (2) the third cut occurs outside the core. Mode (2) is excluded, meaning that triple cuts yielding two cores are not performed by the Hussain-Rea algorithm.

In principle, quadruple and higher cuts are possible. However, the authors demonstrate that cuts beyond triple are "… only likely to result in a small increase in the number of unique MMPs found."

Indexing

The Hussain-Rea algorithm proceeds in two phases:

- Fragmentation. For each molecule in the set perform all feasible single, double, and triple cuts.

- Indexing. Generate a key-value store with fragments as keys and values as cores.

The result is a table, most likely in the form of an indexed database table or an in-memory hash table. The entries of the index are generated as follows:

- Select one, two, or three acyclic single bonds to cut.

- Cut the bond(s).

- Aggregate the non-core fragments into a single key

K. - Find the value

Vfor the keyKin the index. If none exists, createVas an empty set and add it to the index. - Insert the tuple (core, ID) into

V, where "ID" is the compound's unique identifier.

The result is a key-value store mapping a unique, fragment-based key to a nonempty set of cores.

The authors implement keys K as canonicalized, dot-disconnected SMILES strings. As such, the cores associated with any single or multiple fragment key can be obtained in constant time by backing the index with an indexed database or hash table.

The authors address two other practical considerations:

- the cut operation omits hydrogens, which are usually suppressed

- ways and reasons to filter undesirable fragments

From Index to MMPs and Beyond

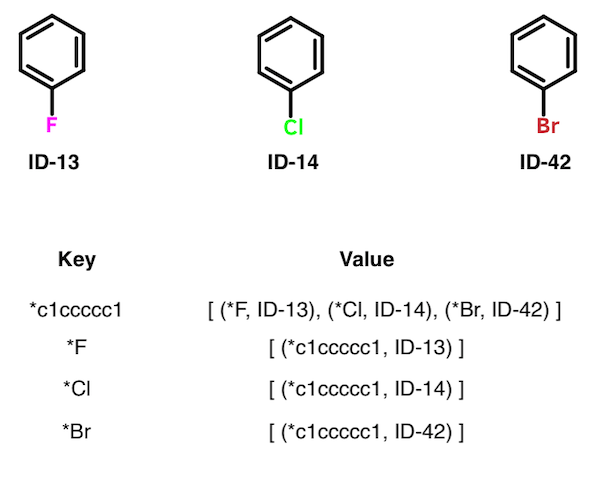

The set of all MMPs can be obtained from the index as follows. For each key K, obtain value V. For each pairing of members in V, extract a pair of unique IDs. Record each pairing of IDs as a single MMP. Skip a value V that contains fewer than two members. In the table below, for example, three matched pairs are extracted from the first entry: (ID-13, ID-14); (ID-13, ID-42), and (ID-14, ID-42)).

Although the authors don't address the topic specifically, it's worth noting that the entries within some values V represent a matched molecular series. Whereas a pair is two structures, a series is two or more. The structures contained within a given value V all differ by the same transformation. For example, the first entry in the table above contains a matched molecular series of size three. An application of this feature by Wawer and Bajorath followed soon after the publication of the Hussain-Rea algorithm.

MMP in RDKit

An implementation of the Hussain-Rea fragmentation algorithm can be found in RDKit's mmpa package. A suite of tools based on this package called mmpdb has also been developed. It fills in some details of the Hussain-Rea algorithm, and provides a convenient SQLite backing for processing large data sets. mmpdb was tested on a data set of 20K structures.

Conclusion

Matched molecular pair analysis is a powerful tool for answering the central question of what compound to test next. Unlike other computational tools, transparency affords MMPs the ability to complement existing molecular design paradigms. The cut and index algorithm introduced by Hussain and Rea can solve not only the problem of efficiently identifying MMPs in large data sets, but other problems as well.