Start Seeing Valence and Core Electrons

Electrons don't get much respect in cheminformatics. Although atoms take star billing in everything from file formats to toolkits to applications, electrons sometimes don't even make the credits. When electrons do find themselves on the cast, they tend to play offstage characters; they are the Mrs. Wolowitz of cheminformatics, sometimes heard but never seen.

A previous article noted some ways in which the marginalization of electrons can degrade cheminformatics data quality. This article continues on that theme, but from the angle of deciding when a bonding arrangement is invalid.

Attributes vs. Computations

Before getting to the problem at hand, it's important to draw a distinction between two fundamental concepts in chemical structure representation:

- Attributes. Read-write values associated with a molecular graph.

- Computations. Values deduced from one or more attributes.

The word "attribute" was chosen carefully. Derived from the French verb for "to assign" (ad- "to" + tribuere "assign"), the word's use here emphasizes that attributes are assigned whereas computations are derived.

Following this distinction to its logical chemical conclusion, attributes usually correspond to particle counts. A case in point is atomic number, otherwise known as proton count. Many computations such as molecular mass depend on it. Another example is neutron count, key to isotopic identity.

Like proton and neutron count, electron count is also an important attribute. Given electron counts on atoms and bonding systems, formal charge and bond order can both be derived as computations.

Casting electron count as a fundamental atomic attribute has some important payoffs. One of them is simplicity. Straightforward, general validation rules can be developed that will work for any bonding arrangement. Because the system is simple, it's easy to develop, test and debug. The lack of exceptions leads to a robust system that can be deployed with confidence.

Atomic Electron Count

Chemistry views molecules as assemblies of atoms held together by bonding relationships. To understand these bonding relationships, it's helpful to mentally build a molecule one step at a time from isolated atoms, as one would assemble the atoms of a physical model kit.

As we're all taught from a young age, an isolated atom is composed of protons, neutrons, and electrons. To a first approximation, instances of each particle type are indistinguishable from each other and so can be represented as count attributes of type unsigned integer. In its starting state, an atom's proton count equals its electron count.

Negative Electron Count is an Error

The presence of an atomic electron count attribute enables chemical transformations to be modeled mathematically. Consider ionization, which mutates an atom's electron count. Electron removal from hydrogen yields a cation (H+), whereas electron addition to hydrogen yields an anion (H-).

Multiple electrons can be added to or subtracted from the atomic electron count, with one proviso: an atom's electron count may never become negative. For example, removing an electron from the hydrogen cation would lead to an electron count of -1, which is physically impossible.

More generally speaking, negative particle counts make no physical sense at all. How should we even attempt to interpret an electron count of -1? We might as well propose a proton count of -42 or a neutron count of -13.

Now consider what happens if charge is mistakenly treated as an attribute. The meaninglessness of H++ is harder to spot. Worse, it becomes much more difficult to tell when a hydrogen-containing molecule is invalid. This creates a dark, cozy breeding ground for bugs. It's exactly the kind of environment that should trigger alarm bells.

Core and Valence Electrons

Although a single electron count suffices for isolated atoms, electron accounting for bonding relationships requires more nuance. Decades of experimental and theoretical work have led to a model that divides an atom's electrons into two categories:

- Valence electrons. Electrons that are used in bonding.

- Core electrons. Electrons that are not used in bonding.

Hydrogen and helium are unique in that the isolated atoms have no core electrons. Atoms with all other elemental identities possess at least two core electrons which never participate in bonding.

An isolated atom's valence electron count is computed by subtracting the atom's atomic number from the atomic number of the previous noble gas. For example, carbon has atomic number six. The previous noble gas, helium, has atomic number two. Therefore, carbon has two core electrons and four valence electrons (6 - 2 = 4). The same rule applies to tennessine, or any other atom.

Covalent Bonding Reduces the Valence Electron Count

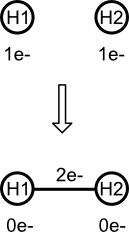

Covalent bonds are formed between atoms by transferring one or more valence electrons to one or more two-center bonds. Put another way, covalent bonding increases the electron count of a bond while decreasing the electron count of all atoms involved. Of course, this level of accounting requires an electron count attribute for both atoms and bonds.

For example, consider the formation of dihydrogen (H2) from two isolated atoms. First, the hydrogen count for each atom is reduced by one. Then the bond's electron count is increased by two (the number of electrons removed from both atoms). Translated to a chemical process, each hydrogen contributes one electron to the covalent single bond. The absence of negative electron count means that the resulting molecule is valid.

More than one electron can be transferred into the same two-atom bond. Dinitrogen (N2) is an example. Each atom possesses five valence electrons. Three of them are transferred from each atom to the bond. Each nitrogen finishes with two valence electrons. The bond finishes with an electron count attribute of six. As described previously, we compute a bond order of three. Again, dinitrogen constructed in this way invokes no negative electron counts and so the representation is valid.

Negative Valence Electron Count is an Error

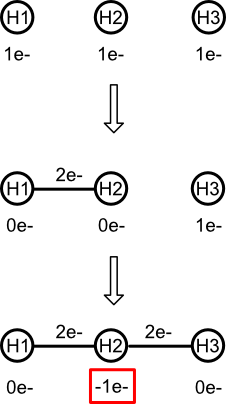

What the valence model absolutely forbids is to put an atom into a state in which its valence electron count is negative. Consider the central atom of trihydrogen (H3), a chain of three hydrogens connected by single bonds. After forming the first bond, the central hydrogen is left with no valence electrons. Attempting to form the second bond results in a negative valence electron count.

It's easy to spot the problem because as noted earlier, atomic hydrogen has no core electrons. Hydrogen's valence electron count always equals its electron count.

The problem comes when we look at atoms with higher atomic number. Take carbon, for example. Should a cheminformatics toolkit ever permit carbon to be taken directly from the isolated, default state to one with more than four covalent bonds?

The answer is clearly "no" because this results in a negative valence electron count. A cheminformatics toolkit should not allow errors like this by default, just like it should not allow negative proton count. The same principles apply regardless of the atom.

Attempting to set a negative valence electron count signals that an error has occurred somewhere. A toolkit should prevent the propagation of such errors.

Hypervalence

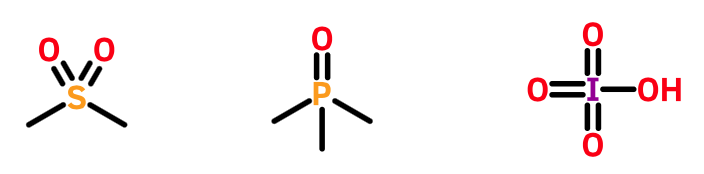

A negative valence electron count should not be confused with hypervalence. As the term was originally defined, hypervalence described a state in which an atom appears to deploy an unusually large number of valence electrons for bonding. For example, phosphorous normally uses just three valence electrons in bonding. However, it can also use all five. Pentavalent phosphorous is therefore hypervalent. With a valence electron count of zero, however, there are no inconsistencies. Whether or not hypervalent atoms should be tolerated on stylistic grounds is another question (see below).

Late main group elements such as sulfur, phosphorous, and chlorine are often found in hypervalent states. None of them involves a negative valence electron count.

Better Terminology

Apparently, chemistry has not as yet invented a term for the principle I'm after. "Hypervalence" clearly is not it. Nor is "hypercoordinate," which also has nothing to do with negative electron count. Until a better term comes along, I'll continue to use the unwieldy workaround "negative valence electron count."

Toolkits and Formats

Chemical representation system are surprisingly tolerant of negative valence electron count. This may have something to do with not recognizing valence electron count as an attribute in the first place. For example, the industry standards SMILES and Molfile are devoid of the concept. Molfile does support radical templates, but that's a far cry from the general-purpose functionality that's needed.

In cheminformatics toolkits, the phenomenon manifests itself with impossible valence states being allowed by default. Recently this blog reported the results of a SMILES validation benchmark. It appears that a few toolkits will not report valence errors for parsed SMILES unless explicitly instructed to do so.

RDKit offers a peek into the complexity of the problem. Trihydrogen, and any other species invoking negative valence electron counts, can be built from scratch without error. Only through the invocation of a dedicated helper function will a valence error be detected.

In contrast, RDKit performs the validation by default on reading a SMILES:

Standardization vs Validation

Should a cheminformatics toolkit ever allow molecular representations based on negative valence electron counts? The RDKit example shows that at least some in the field believe the answer might depend on context.

Others believe that checking should not be done at all by default. Consider this CDK GitHub issue, in which RDKit flags a SMILES for "greater than permitted" valence, but CDK raises no error. In response, John May, the project's maintainer, states:

… Each to their own, personally I believe checks should be done after a valid molecule* is handed back to the user so you can choose to fix them. … *Kekulization complicates this as you have undefined bond order which may/may not be okay. In this case everything is define on input.

I'd suggest that this position mixes two distinct concepts:

- Standardization occurs when cheminformaticians try to decide which of one or more valid molecular representations should be used. An often-cited example is the nitro group. It can be represented using either pentavalent nitrogens or zwitterions. Crucially, neither form invokes negative valence electron count and so both representation are valid. The only issue to be decided is the preferred representation.

- Validation occurs when cheminformaticians seek to exclude species whose representation can not be corrected. Atoms with negative proton counts are invalid and so can't be corrected. Similarly, there's no reliable way to correct a molecule containing an atom with a negative valence electron count. In both cases, the problem almost certainly arises from data entry or programming gone wrong.

ChemCore

ChemCore, the cheminformatics toolkit for Rust, disallows negative valence electron counts by default. This is accomplished by giving each atom an unsigned integer (u8) electron count attribute. Ionization and the creation of bonding relationships mutate this attribute. Any attempt to drive this attribute's value negative yields an error.

For example, the following Rust Jupyter session shows ChemCore's response to trihydrogen:

Note that the error type uses the incorrect term (Hypervalent) and needs to be fixed. Nevertheless, the error is detected by default.

Exceptions

In what situations, if any, should a cheminformatics toolkit tolerate a negative valence electron count? One option might be to allow isolated atoms ionized to the point of losing core electrons. However, this is the realm of physics. A cheminformatics toolkit would have little reason to support this use case.

What about a tool that helps visualize representation errors? For example, it might be helpful for a program to depict an erroneous chemical graph so that the error can be better understood. Although such tools may be useful, it's hard to see how they justify saddling the entire toolkit with an unnecessarily permissive and potentially buggy valence model. A better approach might be to offer such visualizations one level further down. For example, ChemCore's SMILES handling is based on Purr. This library performs no validation other than that required by the OpenSMILES specification. As such, atoms with negative valence electron counts are allowed because OpenSMILES says nothing on the topic. A visualization tool that worked with Purr could then avoid the conflicts that could arise from allowing negative valence electron count on atoms at the cheminformatics toolkit level.

Conclusion

Valence electron count is an important and often ignored atomic attribute. Like any particle count, a negative value is physically meaningless. Molecular representations invoking negative valence electron count should therefore be treated as errors. Doing so is a simple, reliable and inexpensive method to ensure data quality.