Edmonds' Blossom Algorithm Part 1: Cast of Characters

Many problems in business and science can be cast in terms of graph matching. Given an undirected graph, a matching is a subgraph in which every node has a degree of one. It's often important to find a matching that contains the most possible edges. This is the maximum matching problem.

Although the concept is easy to understand, algorithms for finding maximum matchings tend to be complex. Jack Edmonds reported the first efficient approach in the 1960s, a landmark in computer science history. His "Blossom algorithm" has inspired numerous variations and alternatives over the last several decades. A recurring theme in this work is the tradeoff between conceptual complexity and efficiency.

The Blossom algorithm hits a sweet spot. It's complex enough to be general, but simple enough to be widely implemented. Even so, wrapping one's head around the Blossom algorithm is no easy task. A lot has been written on the topic, but mainly using the tools of symbolic logic and mathematics. This is fine for readers with a background in math and computer science. But for those lacking such background, the Blossom algorithm poses a formidable, seemingly insurmountable, challenge.

This article is the first in a three-part series that takes a different approach. Part 1 presents a short background and a visual guided tour of the components of Edmond's Blossom algorithm. Part 2 shows how these components work together through several illustrative examples. Part 3 connects the conceptual background to a working implementation written in Rust.

- Part 1: Cast of Characters

- Part 2: Visual Examples (TBD)

- Part 3: Implementation (TBD)

Backstory

Before introducing the members of the cast, a brief summary of what brings them together will be helpful. The Blossom algorithm accepts a graph and an arbitrary matching over that graph, which may be empty. The algorithm grows the matching iteratively, attempting to find a way to add one additional edge at each step. Failure to do so terminates the algorithm.

An implementation for a maximum_matching function in Rust might start off as something like:

// hypothetical function signature in Rust

fn maximum_matching(graph: &Graph, matching: &Matching) {

// 1. find the next augmenting path

// 2. if path exists, augment matching with it, then

// call maximum_matching

// 3. otherwise, return

}

Given a Graph and a Matching, the maximum_matching function attempts to increase the number of edges in Matching to the greatest extent.

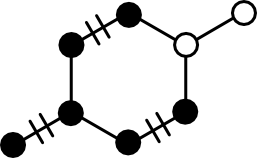

The nature of a Matching deserves some attention at this point. As noted previously, a matching is a subgraph in which all nodes have degree one. The term presumably follows from the idea of two nodes being "matched" together, as two members of an online dating service might be matched.

The key concept in the maximum_matching function is iterative augmentation. Augmentation is the process of increasing the edge count in a Matching. Conceptually, there are two ways to do this:

- Add an edge, neither of whose member nodes are in the

Matching. - Add a path, some of whose nodes are already in the matching.

Option (1) is simple enough. Pick two connected nodes in the graph and add the edge between them to the matching. The problem is that such trivial augmentation might not be possible. The rightmost panel in the above figure gives one example.

Option (2) solves this problem by not adding a single edge, but rather a path. Recall that a path is a type of subgraph that can be expressed as as an ordered set of adjacent nodes. An edge exists between each adjacent pair of nodes, but it need not be explicitly represented.

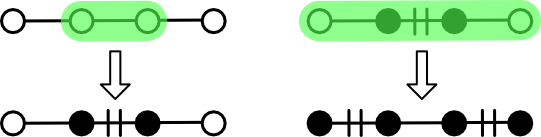

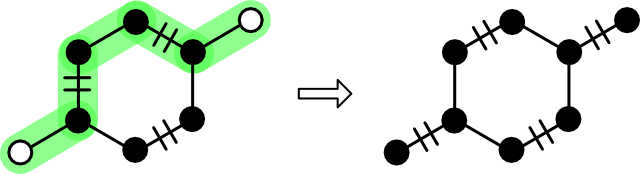

In particular, option (2) calls for the identification of an augmenting path. An augmenting path is an acyclic path containing alternating unmatched and matched edges. Such a path must necessarily be bracketed by unmatched nodes and must have an odd edge count ("odd path"). Although edges alternate in their matched status, all interior nodes will be matched. For this reason, the problem of finding an augmenting path largely boils down to finding an alternating path of matched nodes for which unmatched bracketing nodes can be identified.

The rules for augmenting a matching with an augmenting path are simple. For each edge in the path, apply the symmetric difference operator to the matching. Symmetric difference, also known as "XOR" and given the circle puls symbol (⊕), leaves an edge in the matching if it is present in either the path or the matching. Symmetric difference appears in a few graph theory contexts such as the derivation of cycles from a basis.

The goal of the Blossom algorithm is to iteratively discover augmenting paths until none can be found. Berge's lemma ensures that the lack of an augmenting path is a necessary and sufficient condition for maximum matching. This explains the overall structure of the maximum_matching function.

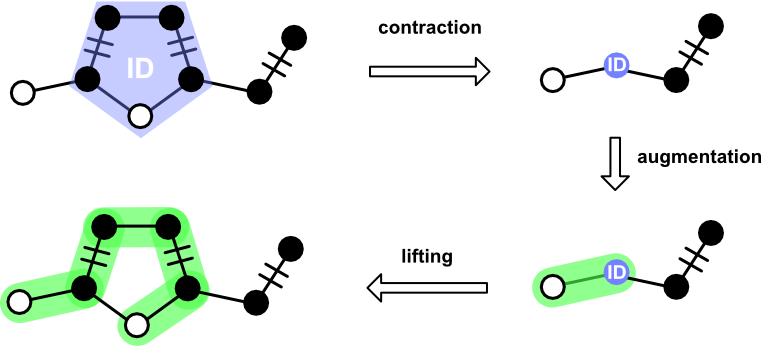

As previously described on this blog maximum matching is conceptually simple provided the source graph is bipartite (no odd cycles). Things get more complicated if an odd cycle is present. The crux of the problem is that without higher-order information it's not possible to know which of the two possible augmenting paths through an odd cycle should be followed.

The Blossom algorithm provides a solution. When an odd cycle is encountered, the source graph and current matching are "contracted," resulting in a new graph and matching in which the odd cycle is replaced by a single node. If an augmenting path using the contracted graph and matching are found, the blossom is "lifted" and processing continues as usual.

Cast of Characters

The Blossom algorithm is complex in that it brings together several actors to find and apply an augmenting path. These actors are:

Graph. A simple, undirected, unweighted graph.Path. A connected subgraph in which all nodes are either degree one or two.Matching. A subgraph in which all nodes have degree one.Forest. A directed acyclic subgraph.Marker. A utility capable of independently marking edges and nodes.Blossom. A utility capable of "contracting" aGraphorMatchinggiven an odd cycle, and "lifting" aPath.

What follows is a detailed description of each role in the Blossom algorithm drama. The responsibilities and operation of each are illustrated.

Graph

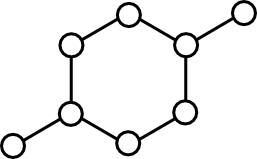

One of the two inputs into the Blossom algorithm is a Graph. In general, a Graph is a set of nodes and edges between them. Within the Blossom algorithm, a Graph contains no self-edges ("loops") or multiple edges.

Despite the utility of graphs in software, relatively little attention has been paid to the fundamental operations that the Graph type must support. Earlier this year I attempted to address this issue in A Minimal Graph API. This article outlines those methods that all graph-like objects should support.

To recap, the Graph type supports the following nine methods, which has been pared down from the original eleven:

- nodes Iterates all nodes.

- order Returns the number of nodes.

- has_node Takes one parameter, returning true if it's a member, or false otherwise.

- degree Takes one parameter, returning its count of outbound edges.

- neighbors Takes one parameter, iterating the nodes connected to it by an outbound edge.

- size Returns the number of edges.

- edges Iterates all edges.

- has_edge Takes two parameters, returning true if an edge exists from the first to the second, or false otherwise.

- is_empty Returns true if the graph order is zero.

Optionally, a Graph may include one or more build methods. These methods convert a system primitive (such as a struct or object literal) into a Graph consistent with it.

Path

A Path is an undirected subgraph expressed as an ordered set of nodes. For each pair of adjacent nodes, a corresponding edge can be found in the parent Graph.

Path supports the following operations:

- add_node Adds a node to the path.

- has_node Returns

trueif the node is present. - length The number of nodes.

A Path could be implemented as a Graph, but this offers little practical advantage. A much simpler approach is to use an array or its equivalent.

It's also convenient for Path to support operations that create a Path in one step.

Marker

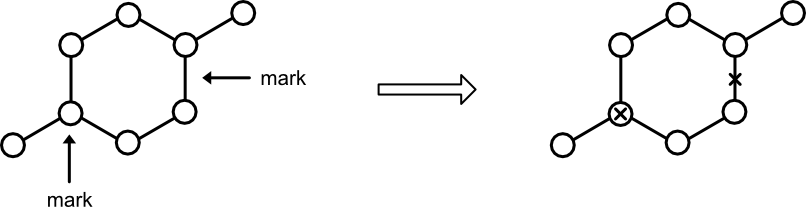

For internal bookkeeping, the Blossom algorithm needs a way to independently mark nodes and edges. This responsibility falls to Marker. Its functionality can either be rolled into Graph or provided through a separate Marker type. The latter approach offers the most generality.

Marker supports the following four operations.

mark_node. Sets the status of a node to "marked."has_node. Returns true if a node has been previously marked.mark_edge. Sets the status of an edge defined by a source and target node as "marked."has_edge. Returns true if an edge has been marked in either direction.

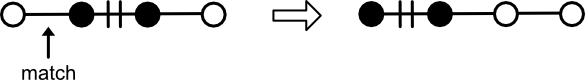

Matching

Matching is the star of the show. Its main responsibility is to maintain a set of edges, ensuring that no edge references the same node twice.

To do this, Matching supports the following operations:

pair. Accepts two nodes, creating an edge between them. If either node is already paired, the edge is broken and the mate deleted. It is an error to pair two nodes that have already been paired.augment. Accepts a path. For each alternating pair of nodes in the path,pairis called. For this reason, it is an error to callaugmenton aPathof even edge count (odd node count).has_node. Returnstrueif the node is paired with another.mate. Returns the node paired to the query node.edges. Iterates the edges comprising theMatching.

Blossom

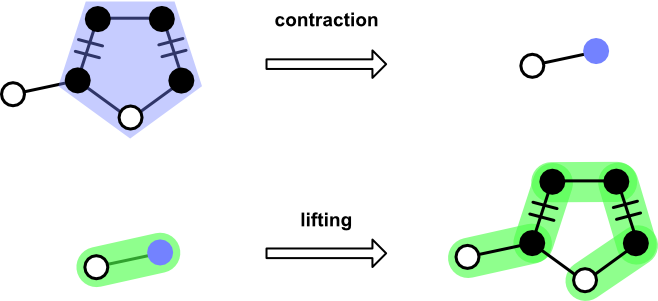

Blossom plays the most complex role. It's not in every scene, but when it does appear onstage, it interacts with most of the other players. The main job of Blossom is to deal with cycles having odd edge counts ("odd cycle").

When an odd cycles is found, a Blossom is constructed from its Path and an ID. These two pieces of information are used during contraction of a Graph and Matching. After an augmenting path has been found, Blossom provides the means to "lift" itself out to yield an augmenting path over the uncontracted graph.

Blossom supports the following operations.

contract_graph. Accepts aGraph, returning a new graph in which the blossom nodes have been replaced by the internal identifier.contract_matching. Accepts aMatchingin which nodes and edges appearing in the blossom cycle have been removed.lift. Accepts aPathcontaining a blossom identifier. Returns aPathin which theBlossomidentifier is replaced by the constituent nodes.

Forest

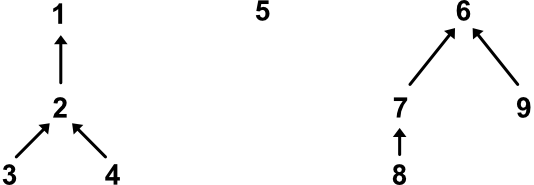

The Blossom algorithm constructs a Forest for internal bookkeeping. A Forest is a directed acyclic graph composed of trees. Each tree is rooted at a single node. A Forest is built by first adding a root node, then adding descendants.

To support its functionality, Forest exposes the following operations:

add_root. Adds a new root node, which will have no parent. It is an error to add the same root twice.add_edge. Builds an edge between a previously-added root and a new child. It is an error to add the same child twice, even if ultimately attached to a different root.has_node. Returns true of the node is in the forest.path. Returns the path from a child node to its ultimate root. The path of a root node contains one member - the root node itself.even_nodes. Iterates those nodes in theForestthat lie an even number of edges away from their roots. Zero counts as even, so roots are even.

Other Resources

The discussion here is based on numerous sources. Two in particular are worth mentioning: the Wikipedia article and an article based on it by James S. Plank. The Wikipedia article is notable for its pseudocode. Although not complete, it does reduce the algorithm to something that could be put into practice in a way that few others do. Plank's article is useful the clarity of its illustrations and use of examples.

Conclusion

What makes the Blossom algorithm hard to understand are all the moving parts. This article takes the first step toward explaining Blossom by offering a high-level view of the parts a sense of their relationship to each other. The next article in this series will discuss in detail how these parts work together with illustrative examples.