Saying No to Browser UI Frameworks

The last seven years has treated front-end developers to a banquet of browser UI frameworks. Names including React, Angular, Vue, Ember, and Backbone frequently top annual roundups and job postings. A host of lesser players also makes an appearance. What gets lost in the hype and buzzwords too often is a clear description of the main problem these tools solve. This post highlights the problem, and offers perspective on why less can be more when building complex browser UIs.

The View Synchronization Problem

Web applications differ in their specifics, but they all pose the same challenge. It inevitably flow from this sequence of events:

- The user takes an action, generating an event.

- The event causes an application state change.

- The view must be changed to reflect the new application state.

Here, "state" refers to the totality of all pieces of information displayable directly or indirectly by the application. For example, state includes:

- whether a button is currently pressed

- whether a menu is currently active

- the current zoom factor

- the location and size of windows

- the configuration of objects specific to the application domain (e.g. "model")

And so on.

For lack of a better term, I call the challenge of synchronizing the view with application state the "View Synchronization Problem." Of course, this problem is hardly unique to browser-based applications. All applications need a way to update state while synchronizing one or more views.

What makes browser UIs unique is the Document Object Model (DOM). A DOM is an in-memory tree of objects that map more or less 1:1 to HTML elements. A single root node usually serves as the ultimate ancestor for every node comprising the user interface. For all its complexity, rendering can be boiled down to producing a DOM tree consistent with the current application state.

Solutions

The cleanest approach to the View Synchronization Problem, conceptually at least, would be to re-render the DOM tree after each user action. Rendering could then be expressed as a function of application state. Mathematically, we might express the relationship as:

where:

- is the DOM tree representing the view

- is the application state

The big win here is the declarative expression of the user interface. For example, in JavaScript we might write something like this:

// naive, impractical approach

const render = (state) => {

// TODO: analyze state

const html = [

'<div id="ui">',

// HTML content consistent with state

'<div>'

];

return html.join('');

};

document.querySelector('#app').innerHTML = render(state);

This naive approach can work for small applications, but things quickly degrade with scale. Performance is sometimes cited as a problem ("the DOM is slow"), and it can be with large collections of nodes. But a bigger problem is what this approach can do to the application using it. For example, re-rendering the DOM tree would mean re-attaching event listeners, some of which may have state of their own. The need to manage these re-attachments could quickly negate the original promise: simplicity.

Alternatively, an application can update only those DOM nodes affected by a user action. This approach requires a way to identify the relevant nodes and make the appropriate change. As before, the solution scales poorly with increasing DOM node count.

Sometimes a divide-and-conquer approach can work. An application is divided into zones of responsibility, each of which is responsible for listening to and updating its own DOM tree. The main limitation of this approach arises with state changes that affect multiple zones. When that happens, complexity returns with a vengeance. Listeners start popping up everywhere and program flow becomes as tangled as a pile of coat hangers.

Frameworks

One way to distinguish today's major browser UI frameworks is their approach to DOM updates. The most popular is Virtual DOM (VDOM). Like a DOM, a VDOM is a tree representing an application's view. Unlike a DOM, a VDOM is not rendered. Instead, a VDOM is compared with a DOM to identify those nodes to create, delete, or update in a process called reconciliation. VDOM and reconciliation are most often associated with React and Vue. Other frameworks offer different approaches.

The Case against Frameworks

At this point, it's useful to distinguish between frameworks and libraries. Definitions vary, but for the most part the distinction relates to developer control.

Whereas developer code calls a library, a framework calls developer code. For example, Ruby on Rails, Django, and Android are frameworks in that their main purpose is to call developer code filling in certain blanks. In this way, a framework drives the organization and structure of developer code. JQuery and (to a lesser extent) Boost act as libraries because developer code calls it. A library has little effect on the structure or organization of developer code. More technically, a framework's organizational principle is Inversion of Control, sometimes known as the "Hollywood Principle." Don't call us, we'll call you.

Inversion of control can impose more than just coding restrictions. For example, frameworks can trigger compiler dependencies. React uses JSX, a domain-specific language that combines JavaScript and HTML. Using JSX creates a dependency for tooling that supports it such as editors and compilers. Although it's possible to forego JSX, this isn't as common. Straying from the "happy path" when using a framework is rarely without costs in that most documentation and support will assume you're on it.

A personal experience taught me that even a framework that does something not possible any other way should be approached with great caution. In 2009 my company began porting a browser component (ChemWriter) from Java to JavaScript. The tooling for JavaScript, HTML, and CSS at the time can charitably be described as barbaric. Not coincidentally, Google had just open sourced its Closure UI library. Using the library required opting into Closure's module system. At the time this seemed like a win because JavaScript had no module or build system compatible with large projects.

What wasn't entirely clear at the time was how the "Closure Library" more closely resembles a framework rather than a library due to the bespoke module system it imposes.

Eventually, JavaScript got built-in module support. It's now possible to build highly interactive applications without much of a library at all (see below). However, Closure has seeped into every nook and cranny of ChemWriter. It's impossible to disentangle this "library," thanks to the Closure module system that was part of the deal. As Closure becomes ever more irrelevant, the decision to use it looks more ill-advised.

Here's the lesson I draw. A framework should not be judged by the standard of solving today's problems, but by the standard of carrying its weight well into the future. Some software isn't destined for legacy status, but a lot of it is. And it's quite difficult to tell the difference.

Like steady rainfall on a mountain, time will erode the advantages of today's browser UI frameworks. What remains will be tightly-coupled dead weight.

A Practical Alternative

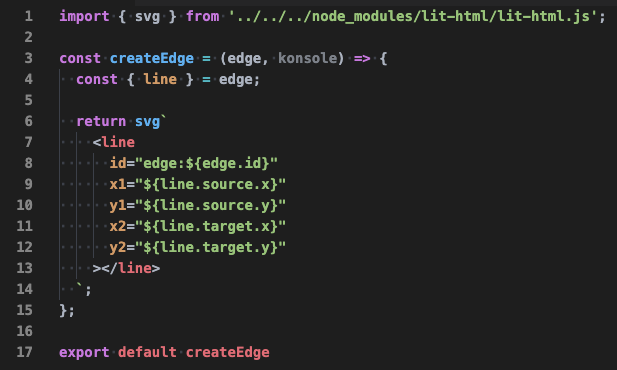

Since the appearance of React, a number of libraries addressing the View Synchronization Problem have been released. I find one in particular compelling due to its small size and limited scope: lit-html.

lit-html is a 3KB library that leverages existing Web standards to enable fast DOM updates — without a VDOM or manual DOM management.

Consider a simple application using the naive re-render approach described earlier. Pressing a button increments a counter. A UI element should report the number of clicks. We might write such a UI like this:

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html lang="en">

<head>

<meta charset="utf-8">

<title>Naive Render</title>

</head>

<body>

<button type="button">Increment</button>

<div class="counter"></div>

<script type="module">

let count = 0;

const template = () => `

<p>Count:</p>

<p>${count}</p>

`;

document.querySelector('.counter').innerHTML = template();

document.querySelector('button').addEventListener('click', e => {

count++;

document.querySelector('.counter').innerHTML = template();

});

</script>

</body>

</html>

The UI consists of a listener added to the button. When called, it updates the count field and completely re-writes the the innerHTML of the counter element using innerHTML.

Chrome developer tools allow us to monitor updates to the DOM by reporting a purple flash around those elements that were updated. As expected, the naive approach updates the entire DOM tree from the counter element down.

Compare this behavior with the alternative using lit-html. The overall structure of the event handler is similar. After updating the count field, the UI is re-rendered.

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html lang="en">

<head>

<meta charset="utf-8">

<title>lit-html Render</title>

</head>

<body>

<button type="button">Increment</button>

<div class="counter"></div>

<script type="module">

import {html, render} from 'https://unpkg.com/lit-html?module';

let count = 0;

const template = () => html`

<p>Count:</p>

<p>${count}</p>

`;

render(template(), document.querySelector('.counter'));

document.querySelector('button').addEventListener('click', e => {

count++;

render(template(), document.querySelector('.counter'));

});

</script>

</body>

</html>

The difference here is that render doesn't naively replace the entire DOM subtree at counter. Instead, lit-html only updates the part of the DOM that changes. And that's just the text node of a single paragraph element.

lit-html comes with some nice add-ons as well, including syntax highlighting for VS Code.

Conclusion

Browser user interfaces are unique in their use of a DOM. A crucial challenge faced by all browser application developers is how to update the DOM in response to application state changes. Many solutions to this problem have been developed over the years. Several frameworks, including React and Vue, are currently very popular. This article makes the case for considering far simpler and less invasive options.