A Smallest Set of Smallest Rings

Cycles within molecular graphs (aka "rings") play a central role in many chemistry subdisciplines. Not surprisingly, computational chemistry and cheminformatics procedures often depend on cycle perception. But cycle perception turns out to be much more complex than first appearances suggest. Part of the problem is the sheer number of approaches. Compounding the problem is the vast literature on the topic, most of which is written by and for experts.

Of all the angles from which cycle perception in cheminformatics can be approached, one stands out for its historical and conceptual importance: Smallest Set of Smallest Rings (SSSR). This article takes a closer look at SSSR, describing the problem it solves and its limitations.

Why Not All Cycles?

As the name suggests, an SSSR is a subset of cycles within a molecular graph. Before going further, it's important to understand why a cycle subset should be used in the first place. Can't any problem be solved with the set of all cycles?

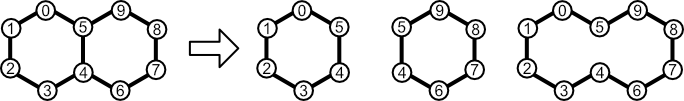

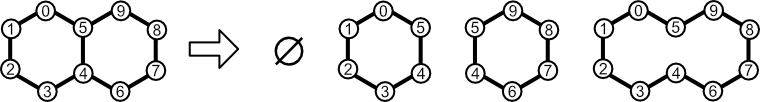

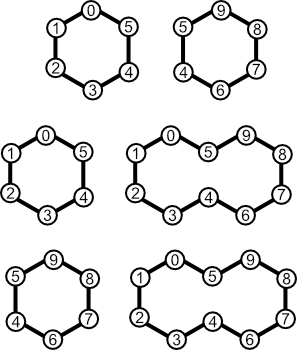

Imagine computing the cycle membership of each atom in a decalin molecule. The set of all cycles contains three members: two of length 6 and one of length 10 (where "length" refers to the number of edges). Naive application of the set of all cycles would lead to the conclusion that the bridgehead atoms (4, 5) participate in three cycles and the other atoms (0, 1, 2, 3, 6, 7, 8, 9) participate in two. For certain niche applications, this might be a suitable result but in others it will not.

Cheminformatics algorithms often require a set of cycles that filter "envelopes," leaving only the smaller, more relevant cycles. This is a surprisingly difficult problem, as evidenced by a long line of papers extending back to the 1960s. For in-depth discussion of several of them, see Counterexamples in Chemical Ring Perception.

Welcome to Cycle Space

Before discussing ways to filter cycles, it's crucial to put the entire concept of cycle sets on a more solid mathematical footing. The key to doing so is cycle space. The definition of cycle space for a simple graph G by Gross and Yellen is both concise and instructive:

The cycle space of a graph G, denoted by Wc(G), is the subset of the edge space WE(G) consisting of the null set (graph) ∅, all cycles in G, and all unions of edge-disjoint cycles of G.

This definition implicitly views each member of cycle space as a subset of edges in G. The null set (∅) has no edges and is therefore empty. The definition also references "unions of edge-disjoint cycles," which is explained in the next section. Before that, some definitions will help avoid confusion when talking about cycles:

- edge space: the set of all edges in G

- cycle: "a non-empty trail in which the only repeated vertices are the first and last vertices"

- trail, walk: "A walk is a finite or infinite sequence of edges which joins a sequence of vertices. … A trail is a walk in which all edges are distinct."

To summarize these definitions, a cycle in graph G is a nonempty sequence of adjacent edges in which only the first and last nodes repeat. Two practical consequences follow: (1) a cycle has at least three edges; and (2) the nodes of a cycle have degree two.

To make this more concrete, consider decalin. Its cycle space, like all cycles spaces, contains the empty cycle ∅. Additionally, the three cycles enumerated in the previous section are also present.

Cycle Math

Cycle space's mathematical grounding enables provable statements and valid generalizations to be made. This grounding desirable because it's wasteful to work on implementing an algorithm only to discover a counterexample.

The math behind cycle space is based on an addition operator ("⊕"). As we'll see, cycle addition is defined in such a way that cycle space is closed with respect to it. This means that adding any member of a cycle space with any other member (including itself) yields another member of cycle space.

Closure with respect to an operation is a common property in many well-behaved systems. For example, the integers are closed with respect to addition. Summing any of them yields another integer.

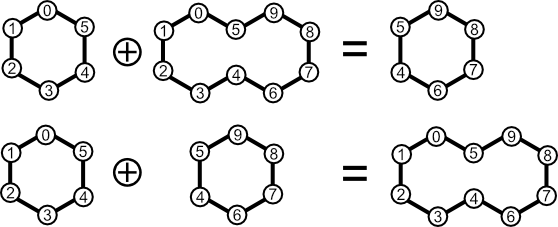

The cycle addition operation is based on a concept borrowed from mathematics called symmetric difference (aka "XOR"). Given two sets, S1 and S2, a symmetric difference yields a new set that includes all members present in either S1 or S2, but not both.

Viewing a cycle as a set of edges, we can define addition using just two rules:

- if an edge exists in one cycle but not the other, include it in the sum;

- if an edge exists in both cycles, exclude it from the sum.

Consider the members of the cycle basis for decalin. Adding the two small cycles together yields the large cycle. Likewise, adding one of the small cycles with the large cycle yields the other small cycle. Finally, adding any cycle with itself yields the null cycle, also a member of cycle space as defined in the previous section.

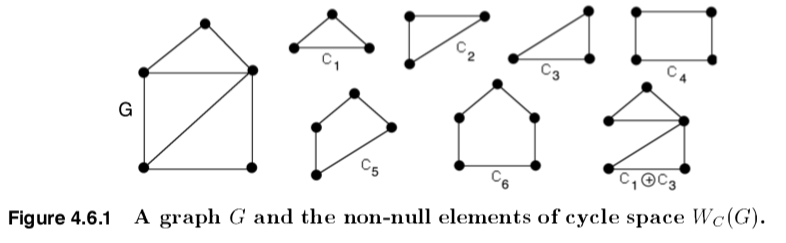

One nuance of cycle addition deserves special attention: symmetric difference doesn't always yield a cycle. In other words, cycle space isn't just populated with cycles and the null cycle. The book by Gross and Yellen linked to in the previous section contains this rather thought-provoking figure:

C1 through C6 look like cycles, but why is C1⊕C3 included in the cycle space for G? This subgraph (also known as the butterfly graph) clearly isn't a cycle, but is nevertheless a member of a cycle space. This follows from the definition for cycle addition. The cycle space for G contains both cycles and all "unions of edge-disjoint cycles," where "union" means cycle addition. The butterfly graph is the symmetric difference of cycles C1 and C3.

From this vantage point, we can appreciate the simplified definition of cycle space given by Wikipedia:

In graph theory, a branch of mathematics, the (binary) cycle space of an undirected graph is the set of its even-degree subgraphs.

Cycles clearly fit the definition of "even-degree subgraph", but so do certain non-cycles. The butterfly graph is not a cycle, but it is an even-degree subgraph of G, just like the other members of the graph's cycle space.

Cycle Basis and Cycle Rank

Cycle space and cycle addition suggest a special role for certain cycles. In particular, some members of cycle space can be viewed as precursors to other members. We call the set of cycles capable of producing all members of a cycle space a cycle basis. A given cycle space can have one or more cycle bases. Each of them contains the same number of cycles.

To make this more concrete, consider the three cycle bases of decalin. Each contains not three cycles, but only two. All members of cycle space can be obtained through addition of one basis member to another (or itself).

It's often useful to know how many cycles are present in the cycle bases of a graph G. The answer can be found by computing the cycle rank for G. This value, which is also known as "cyclomatic number" or "Frèrejacque number," represents the size of the cycle bases G. It also represents the number of edges that must be removed from G to yield an acyclic graph.

Cycle rank () is computed as:

where:

- is the number of edges (size)

- is the number of nodes (order)

- is the number of connected components

For example, the cycle rank for decalin is two (11 - 10 + 1). From this we conclude that any cycle basis for decalin should contain two members. Similarly, we predict that removing just two edges from decalin will yield an acyclic graph. Inspection proves both predictions to be valid.

Minimum Cycle Basis

It should now be clear that: (1) the cycle space of a graph G can be represented with a subset of cycles called a basis; and (2) a graph can posses multiple cycle bases. Therefore, the problem of filtering useless cycles boils down to choosing a cycle basis.

A 1970 paper by Plotkin described the first widely-implemented procedure for doing just that. The crux of Plotkin's analysis is contained in "Procedure P", which yield a "smallest set of smallest rings." Procedure P can be summarized as follows:

- Identify the set of all cycles C.

- Order the members of C by ascending edge count.

- Create an empty set S that will contain the SSSR.

- Add the first member of C to S.

- For each remaining cycle in C, Cn, add Cn to S only if it is not the sum of cycles already added to S.

Think of Procedure P as a method for describing the contents of an SSSR, not necessary the best way to implement SSSR in software. Plotkin's paper itself goes on to describe a different algorithm for finding an SSSR. Since then, others have been published.

SSSR turns out to be equivalent to the concept of Minimum Cycle Basis (MBC). The first polynomial time algorithm for finding MCB was reported by Horton in 1984. A twist on the idea was later published.

SSSR and Uniqueness

Although the set of all SSSRs for a graph G is invariant, a single SSSR is not. This feature has been the topic of sometimes prickly debate, as exemplified, by OpenEye Software's provocatively-titled essay Smallest Set of Smallest Rings (SSSR) considered Harmful.

Consider finding an SSSR for decalin. The cycle rank (2) ensures SSSR sizes of two. Procedure P yields an SSSR containing two cycles, each of length 6. SSSR yields an invariant set of cycles because only one SSSR exists.

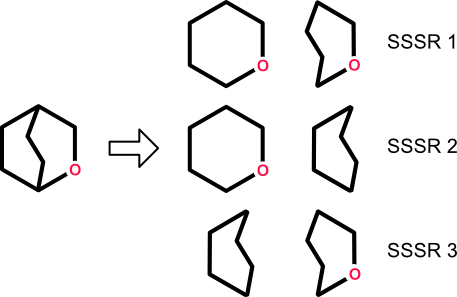

But this is a special case. Consider repeating the procedure with oxabicyclo[2.2.2]octane. The cycle rank is 2 (9 - 8 + 1). The cycle space of the molecule contains three cycles of length 6, implying that one of them must be dropped to make an SSSR. Which one should it be — the carbocycle or one of the heterocycles? According to Procedure P, any of them can be discarded. The upshot? Two of three possible SSSRs contain a carbocycle paired with a heterocycle. A third SSSR contains two heterocycles.

This lack of determinism makes SSSR ill-suited for many cheminformatics applications. In particular, any analysis that requires the enumeration of cycle membership will fail to return consistent results under SSSR in the general case. Global analyses (e.g., heterocycle/carbocycle count) can fail for the same reason.

This problem becomes especially vexing if SSSR is codified into standards. Perhaps the best-known example can be found in the SMARTS language which is tightly coupled to SSSR through the ring membership and ring size primitives (R<n> and r<n>, respectively). The first primitive counts the number of SSSR rings in which an atom appears, and the second counts the smallest SSSR ring size. Clearly these properties are not invariant and will therefore lead to erroneous, nondeterministic results. SMARTS patterns including these primitives should be avoided. Algorithms and implementations should adopt SSSR only when determinism can be proven unnecessary.

Conclusion

Smallest Set of Smallest Rings was the first widely-used cycle set in cheminformatics. It offers a limited solution to the problem of molecular cycle perception. Unlike the set of all cycles, an SSSR can filter useless or interfering envelope cycles. Unlike the set of all cycles, an SSSR offers no guarantee of uniqueness. A given molecular graph can produce multiple SSSRs with no constraints on which one will be obtained. This lack of determinism interferes with many of the applications for cycle sets. Future articles will return to this problem and describe some solutions.