Wrapping Rust Types as Python Classes

Python has evolved into scientific computing's standard orchestration language. In this role, Python sits at the top of a software stack, directing the actions of components written in low-level languages below. This architecture allows Python to deliver developer productivity while the low-level language delivers performance. This system requires a robust communication channel, which is typically supplied by a "Python wrapper."

The recent maturation of Rust as a stable, full-featured systems programming platform raises the possibility that it could replace C and C++ in some Python orchestration scenarios. My own interest lies in using a cheminformatics library written in Rust from Python.

A lot has been written about calling Rust code from Python. In researching the topic, however, I found that most documentation begins and ends with simple functions. Python and Rust both support object-oriented programming features, but using them through a wrapper requires non-obvious, lightly-documented refinements. This article fills the gap by showing how to build a Python wrapper for a nontrivial, persistent Rust object.

Prerequisites

This tutorial assumes that you've installed a Python 3 interpreter and a Rust compiler.

Overview

The project's goal is to wrap a subset of Rust's HashSet type, an unordered collection of unique values. Like most languages, Python already includes this functionality. So the objective isn't practical but rather educational. Using HashMap simplifies the project, allowing it to fucus on the Rust and Python interfaces themselves.

The wrapping technique can be summarized as follows:

- Write a Rust FFI interface.

- Write a Python Ctypes interface

- Write a Python API.

- Test the Python API.

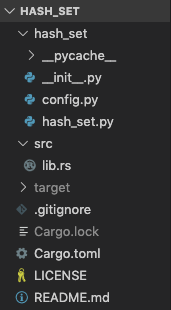

Here's the directory layout for the project:

__pycache__ is added by Python when the wrapper is imported.

Several sources proved crucial in my research on this topic, including:

- The Rust FFI Omnibus. A cookbook illustrating various FFI wrapping scenarios, with support for Ruby, Node, Python, Java, C, C#, Julia, and Haskell.

- The Unofficial Rust FFI Guide. I found the section on error handling and return types especially helpful.

- Calling Rust From Python. A detailed example of Rust object instantiation and control from Python using a somewhat different approach than presented here.

- passing arrays with ctypes. From StackOverflow.

- Dereference FFI pointer in Python to get underlying array. From StackOverflow.

The full project is fairly small. Even so, you may wish to download it from GitHub.

Create a Project

We begin by creating a Rust project in the usual way.

cargo new hash_set --lib && cd hash_set

Rust FFI Interface

The Rust side uses Foreign Function Interface (FFI), a general-purpose mechanism for producing a binary suitable for bindings in not just Python, but other languages. The interface consists of a set of isolated methods that work together to produce an object lifecycle with a constructor, destructor, and methods.

First, we bring in two dependencies: the HashSet type itself (which will be wrapped) and the size_t type from libc. The latter allows translation between certain Rust primitive types and their corresponding C constructs.

// src/lib.rs

use std::collections::HashSet;

use libc::size_t;

Next comes a function to construct a HashSet and return it to the caller - ultimately Python. Rust's most unusual (and powerful) feature is compile-time memory management in which values are allocated on the stack by default. We bypass this by moving the HashSet instance to the heap via Box, then returning a raw pointer to it.

// src/lib.rs

#[no_mangle]

pub extern "C" fn hash_set_new() -> *mut HashSet<usize> {

let result = HashSet::new();

Box::into_raw(Box::new(result))

}

A HashMap instance allocated in this way will eventually need to be deallocated. The hash_set_delete function enables memory allocated by Rust to be cleanly reclaimed.

// src/lib.rs

#[no_mangle]

pub extern "C" fn hash_set_delete(set: *mut HashSet<usize>) {

if set.is_null() {

return;

}

unsafe {

Box::from_raw(set);

}

}

// ...

This function is remarkably straightforward. We first check that the raw pointer is not null. If not, we bring the HashSet instance into scope on the stack. Rust's compile time memory management does the rest, freeing the memory as expected.

With the birth and death of a HashSet defined, we can begin to define its functionality. For this we use a set of functions, each of which follows the same basic pattern:

- De-reference the pointer to the Rust instance.

- Use the Rust instance to obtain a result.

- Report the result.

Take, for example, the contains method, which returns a boolean indicating whether a value is a member of the HashSet.

// src/lib.rs

// ...

#[no_mangle]

pub extern "C" fn hash_set_contains(

set: *const HashSet<usize>, item: size_t, result: *mut bool

) -> i8 {

let set = match unsafe { set.as_ref() } {

Some(set) => set,

None => return -1

};

let result = match unsafe { result.as_mut() } {

Some(result) => result,

None => return -1

};

std::mem::replace(result, set.contains(&item));

0

}

// ...

The first thing that jumps out is that the return type is used to to signal success/error conditions, whereas an input parameter pointer store the actual result. This pattern is common in FFI libraries. The idea is that native wrapper code should never panic on an error condition, but instead report an error as a return value. In the case above, the error condition will be reported as -1 and success as 0. Although not pursued here, we could take this idea one step further with a thread-local last error code.

The boolean result is passed as a raw pointer whose value is re-written by a call to std::mem::replace. In other words, the Python side will be responsible for managing the memory of the result, eliminating the need for bloating the Rust side with this cleanup. As we'll see below, it turns out that Python is very well-suited to this approach.

Although the remaining functions follow a very similar pattern, one point of interest is the collect method wrapper.

// src/lib.rs

// ...

#[no_mangle]

pub extern "C" fn hash_set_collect(

set: *const HashSet<usize>, result: *mut size_t

) -> i8 {

let set = match unsafe { set.as_ref() } {

Some(set) => set,

None => return -1

};

let items = set.iter().cloned().collect::<Vec<_>>();

unsafe {

std::ptr::copy((&items[0..]).as_ptr(), result, items.len());

}

0

}

// ...

On the Python side, the HashSet::collect method returns the elements of the set as a list. Keeping with the theme that Python will manage its own memory, the list is written to a raw output parameter pointer using std::ptr::copy.

The library is built in the usual way with Cargo, storing the binary in target/debug.

cargo build

Python Ctypes Interface

Python wrappers to Rust libraries tend to follow a common layout pattern. Within the Rust project is found a directory named after the project, in this case hash_set. This is where the Python module lives. Create this directory and add the init file:

mkdir hash_set

touch hash_set/__init__.py

__init.py brings two objects within scope: a lib object exported from the config modules and representing the Rust library; and a HashSet class.

# hash_set/__init__.py

from .config import lib

from .hash_set import HashSet

The lib object is built through a call to config/load_lib. This function begins by tracking down the Rust library, then defining the argument types (argstype) and return types (restype).

# hash_set/config.py

def load_lib():

prefix = {'win32': ''}.get(sys.platform, 'lib')

extension = {'darwin': '.dylib', 'win32': '.dll'}.get(sys.platform, '.so')

lib = ctypes.cdll.LoadLibrary(prefix + "hash_map" + extension)

lib.hash_set_new.restype = POINTER(HashSetS)

lib.hash_set_len.argstype = (POINTER(HashSetS), POINTER(c_size_t), )

lib.hash_set_len.restype = c_int8

lib.hash_set_contains.argstype = (POINTER(HashSetS), POINTER(c_size_t), POINTER(c_bool), )

lib.hash_set_contains.restype = c_int8

lib.hash_set_insert.argstype = (POINTER(HashSetS), c_size_t)

lib.hash_set_insert_restype = c_bool

lib.hash_set_collect.argstype = (POINTER(HashSetS), POINTER(POINTER(c_size_t)), )

return lib

The definition of argument and return types is made possible with ctypes, "a foreign function library for Python." As can be seen above, one of the jobs of ctypes is to help Python interpret the arguments and return values of FFI functions.

Python API

The lib object produced through ctypes assignment is available by importing it from the top-level module. The file hash_set.py leads with this import together with the import of types needed from the ctypes library.

# hash_set/hash_set.py

from ctypes import c_size_t, c_bool, byref

from hash_set import lib

class HashSet:

def __init__(self):

self.obj = lib.hash_set_new()

def __del__(self):

lib.hash_set_delete(self.obj)

# ...

The two methods __init__ and __del__ govern specific points in the lifecycle of HashSet. __init__ is invoked just before the Python constructor returns. __del__ is invoked sometime after a Python HashSet instance goes out of scope.

The remaining HashSet methods deal with the orchestration of Python ctypes and the Rust FFI library. As on the Rust side, a pattern emerges:

- instantiate and initialize ctypes

- invoke the appropriate

libmethod - process the Rust FFI return value and ctypes

- return a result or raise

Take, for example, the contains method, which was was previously discussed from the Rust side.

# hash_set/hash_set.py

# ...

class HashSet:

# ...

def contains(self, item):

result = c_bool()

if lib.hash_set_contains(self.obj, item, byref(result)) < 0:

raise ValueError

else:

return result.value

# ...

The remaining HashSet methods follow a similar pattern. In analogy with the Rust side, the collect method deserves special mention.

# hash_set/hash_set.py

# ...

class HashSet:

# ...

def collect(self):

result = (c_size_t * self.len())()

if lib.hash_set_collect(self.obj, byref(result)) < 0:

raise ValueError

else:

return list(result)

# ...

HashSet#collect passes a pointer to a Python ctype array. The Rust side uses this pointer as a starting point to fill the array. However, the Python c_size_t instance must be instantiated with a length equal to the number of items in the Rust collection. A call to self.len makes this possible.

Testing

From the outside, HashMap looks an acts like other Python classes. Instantiation works in the usual way, and there is no need for clients to explicitly "destroy" an instance after creation.

LD_LIBRARY_PATH=target/debug python3

>>> import hash_set

>>> from hash_set import HashSet

>>> s = HashSet()

>>> s.contains(0)

False

>>> s.insert(0)

True

>>> s.contains(0)

True

>>> s.insert(0)

False

>>> s.insert(1)

True

>>> s.len()

2

>>> s.collect()

[1, 0]

Unix users should be able to use the LD_LIBRARY_PATH prefix to locate the library. Windows users can copy the binary into the current working directory.

Automation

Building a Pythonic Rust wrapper at the low level presented here is very informative, but won't be right for every project. As we've seen, past a point the work is pure repetition.

This raises the possibility of automating the process, but to my knowledge not much along these lines exists. Bindgen "automatically generates Rust FFI bindings to C (and some C++) libraries." This is not the direction of interest, which is to produce C FFI bindings to Rust libraries. At first glance, cbindgen looks promising, but it "creates C/C++11 headers for Rust libraries which expose a public C API." We don't need headers. Finally, Swig doesn't yet directly support Rust, although an indirect approach might be feasible. Rust Swig (aka flapigen-rs) connects "programs or libraries written in Rust with other languages," but so far Python is not directly supported. PyO3, which has been discussed here previously, offers "Rust bindings for Python," but the need to manually set up both the Python and Rust APIs remains.

RustPy appears to automate some of the tasks presented here, but I haven't worked with it and don't know the scope or limitations.

Conclusion

Hand-coded Python wrappers for Rust libraries are straightforward to build given some simple tools and concepts. The Rust side defines an interfaces of functions recapitulated on the the Python side as a class. The approach is fully capable of yielding wrappers that look and feel like ordinary Python libraries. What hasn't been discussed yet is packaging and distribution, but that's a story for another time.