Security Theater and the Blockchain Project

The word "blockchain" is working its way into scientific publications, symposia, and I suspect, grant applications. Several groups now seek to apply this technology to old problems such as ensuring data integrity in regulated environments including drug manufacturing and clinical trials. A recent example authored by a group from UCSF appeared earlier this year in Nature Communications.

This paper, like similar proposals I've read over the past several years, unfortunately stands on shaky technical ground. The weakness arises from misunderstanding and misapplication of the underlying technology. Propagation of similar errors will, I fear, wastefully suck millions of dollars from stretched research budgets. This article highlights the UCSF paper's major issues while presenting a more sound description of the underlying technology. No background in advanced math or cryptography is assumed. Hopefully this article can serve as a resource for those reviewing future proposals.

Roots of Misunderstanding

The UCSF paper's introduction offers this description of blockchain:

Blockchain is a new software development methodology involving a unique data structure that has garnered increased attention due to the seminal paper that outlined Bitcoin (bitcoin. org). The technology provides a data structure that ensure a secure and unfalsifiable transaction history. This is accomplished primarily through the use of cryptographic hashing, which has properties and use cases in many domains ranging from internet security to banking. A hash function is a function that maps data of variable length data to a fixed-length digest. Any change to the input data result in an unpredictable change in the hash. In this implementation, each new block added to the chain includes a hash of the previous block. If the previous block is later changed, the subsequent hash would no longer be valid. In addition, blockchains are designed to be append only, and are thus immutable by design, providing a guarantee of safeguarded data. This yields a verifiable and tamper proof history of all transactions since its beginning.

Here blockchain is defined as both a "software development methodology" and a "tamper proof," "immutable" data structure. Practitioners use the data structure to safeguard underlying data. I won't discuss the dubious claim that blockchain is a software development methodology, but the notion should set of alarm bells if you're familiar with the history of Agile software development.

Instead, this article will focus on the extraordinary claim that blockchain is an "immutable" and "tamper proof" data structure. For now, consider that Satoshi Nakamoto's often-cited white paper describes in detail the conditions under which the Bitcoin block chain can be mutated and tampered with. Also consider that the Bitcoin block chain itself has undergone numerous revisions in its decade-long history.

Terminology

The use of the term "blockchain" (one word without an article) is problematic at best. It has been corrupted by hucksters and con artists for years. Users often dress the word up with its charming partner, "technology." Like snake oil peddled from a covered wagon to desperate settlers, "blockchain technology," has been touted as the cure for all manner of technological ailments. Regardless of its garb, the word "blockchain" obfuscates more than it reveals.

Tellingly, the Bitcoin white paper never uses the word "blockchain." However, its author did use the term "block chain" a few times in forum posts. Only long after Nakamoto's departure from the project did "blockchain" come into widespread use.

For these reasons, this article will avoid the term "blockchain" whenever possible, favoring instead the two words "block chain," and always with an article. Even so, the overly simplified mental picture of a chain of blocks can lead to misunderstandings of the kind on display in the UCSF paper.

The Problem to be Solved

The UCSF paper begins with a discussion of the problems facing clinical trials:

- many parties and sites are involved;

- a lot of data flows between these entities;

- complexity brings the possibility of both accidental and malicious changes to data;

- many manual, error-prone processes are still used;

- enforcing data handling standards has been problematic;

- lack of standardization, coupled with complexity, makes independent auditing difficult; and

- the provenance of data is often not captured.

The authors note that the FDA has identified improved data traceability as an area of high importance. Given the potentially life-altering and lucrative decisions made on the basis of data gathered through a clinical trial, it's easy to see why.

The UCSF Clinical Trial Block Chain

The UCSF team proposes a solution in the form of a centrally-administered Web portal. The portal enforces changes to data-handling methodologies and exposes an underlying block chain. A prototype was built and tested with a publicly-available clinical trial data set.

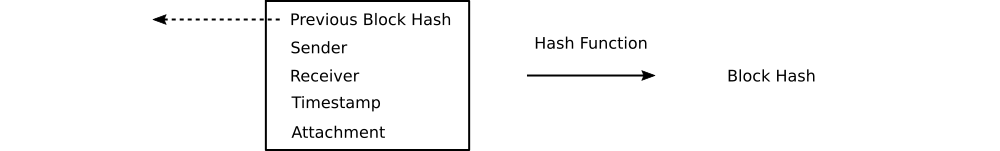

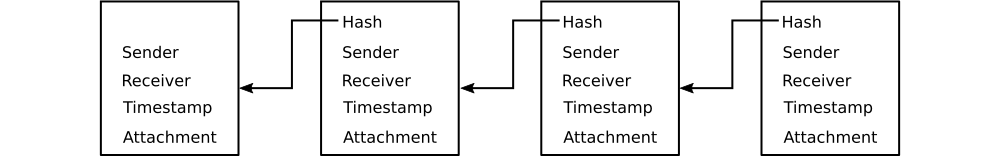

The UCSF block chain adopts a very simple structure. Unlike the Bitcoin block chain, there are no transactions per se, nor does a user-defined program operate over data contained in blocks. Instead, each block consists of a file attachment (presumably a PDF but not necessarily so) and four metadata fields: sender, receiver, timestamp, and hash value of the previous block. Concatenating the attachment and metadata fields, then hashing the result yields a hash value. This value becomes the previous block hash for the next block.

Think of a hash value as a unique, numerical identifier for a piece of digital data. Hashing is a mathematical operation that transforms a blob of arbitrary data into a hash value. Should the input data (e.g., a block) change by flipping so much as a single bit, the hash value output will also change. Moreover, this change is unpredictable. It's computationally impractical to independently discover the data that produced a hash value. However, a hash value can rapidly be verified as having been generated from a piece of source data. In this sense, a hash value serves as a kind of proof of knowledge. For a details, see my article Seven Things Bitcoin Users Should Know about Hash Functions.

The Bitcoin block chain and the UCSF block chain have one feature in common. In both cases a block explicitly references its parent by hash value. This property allows blocks to be assembled into higher level structures.

The procedure for connecting blocks is simple. Pick any block. Then find a disconnected block claiming it as a parent. If none are available, find the block's referenced parent. Connect parent with child. Continue until no block remains unconnected.

If every block (except the first for obvious reasons) claims a unique and available parent, a chain is formed. This chain has a rather useful property. Should a given block's underlying data change in any way, so will its hash value. A change in the block's data propagates to its hash value, breaking the link between the altered block and the next block in the chain.

At first glance it's easy to conclude, as the UCSF team does repeatedly, that the chain-breaking property alone yields meaningful security guarantees. You might even start to think of block chains as "immutable" and "tamper proof" data structures. But you would be mistaken. Understanding why requires a short technical detour.

Block Trees

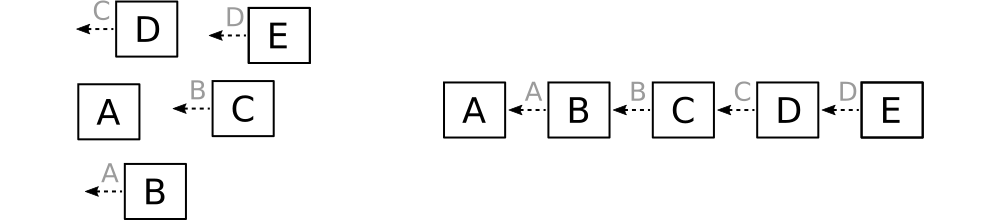

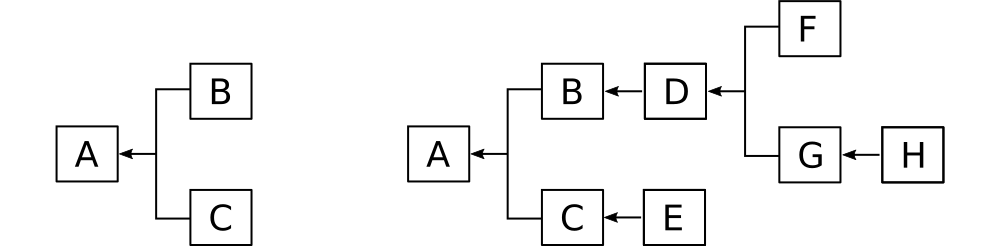

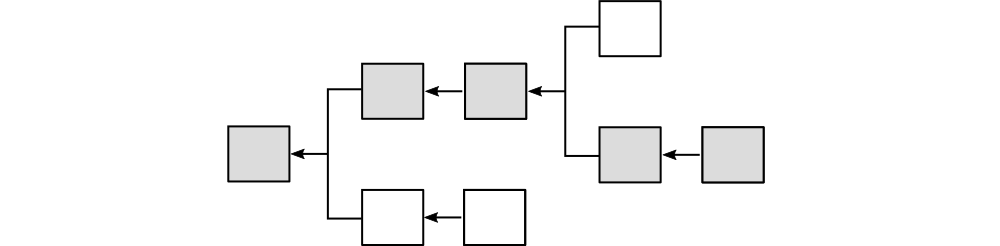

What happens if two blocks reference the same parent? This normal and expected possibility results not in a chain, but a tree.

Imagine, for example, a collection of three generic blocks (A, B, and C). Blocks B and C reference block A as a parent. Using the procedure outlined in the previous section, we assemble not a chain but a tree rooted at A. The same procedure and identical block specification can scale from three blocks to three million blocks.

Clearly, a block chain is merely a special case of a block tree. We can in fact trace a path through a block tree from the root (genesis block) to any terminal to produce a chain. When people speak of a "block chain," (or as will be more likely be the case, "blockchain") most of the time they're thinking of a specific path through a block tree. In Bitcoin, this path is known as the "active chain."

Given a block tree with multiple paths, how can any one of them be chosen as the active chain? Bitcoin uses a protocol called "proof-of-work." In a nutshell, the protocol forces block generators to consume energy and processor cycles by constraining the range of valid block hash values. Network nodes identify the active chain as the one that was most expensive to produce.

Proof-of-work is based on an idea called "Hashcash" first described in 1997. To prevent email spam, it was proposed that a special value (a "proof") be appended to every email. The value, when concatenated with the email message produced a hash value within an acceptable range. The only way to obtain a proof is brute force. By widening or narrowing the range of acceptable hash values, email recipients could make it less or more expensive to produce an email that would be read. Bitcoin extended this protocol to make the writing of blocks provably expensive. Based on the measured rate of block generation, the cost for generating blocks can be regulated up or down by narrowing or widening the range of acceptable block hash values.

This system lays the groundwork for some very effective economic incentives. An attacker attempting to re-write history must commit resources at a high enough rate to generate blocks faster than the rest of the network. Failure to win bleeds the attacker of resources, resulting in ruin if continued long enough.

In effect, Bitcoin makes would-be attackers an offer. They can follow the active chain identified by the rest of the network and receive compensation at a market rate as a reward for "honest" behavior. Or they can build their own active chain, behaving "dishonestly". Profiting from dishonest behavior requires consuming resources at a rate higher than the rest of the network for a sustained period of time. Failure means loss of invested resources without compensation. The system remains secure as long as the reward for honest behavior exceeds the reward for dishonest behavior.

However, this is not the system proposed in the UCSF paper. Indeed, the problem of identifying the active chain is only vaguely expressed and addressed only superficially. This oversight renders the security considerations presented in the paper mostly irrelevant.

Deliberate and Accidental Data Corruption Scenarios

The UCSF paper describes two scenarios in which trial data might be altered after the fact. In the first, the alteration occurs through the portal:

While logged in as the trial sponsor, we attempted to modify the adverse events reported in selected CRFs [case report form] … so as to deceptively bolster treatment approval in a potentially untrustworthy network. … As the trial sponsor, these CRFs were mutated such that no adverse events were listed (Supplementary Note 3, 4). The new tampered replacement files are appended with a version number automatically (Fig. 3b), and the corrupting party, time of modification, and changes are all easily visible. The system is capable of handling multiple versions of files in case the original one is part of a later transaction, or in case further revisions or illegitimate mutations are made. These are designated with incrementing version numbers for each new unique version. Original documents, however, are designated with no version number.

Elsewhere the UCSF team claims that its web portal assigns version numbers to altered documents. The exact mechanism is never explained other than to note it works "similar to the functionality of GitHub." Regardless of the mechanism, it appears tightly coupled to the portal. Bypassing the portal neutralizes this defense.

In the second scenario, data modification occurs outside of the portal:

The second hostile condition we simulated was that of an intentional fault or data corruption at the storage level. In this simulation, we purposefully corrupted the treatment distribution … to check if the infrastructure would detect and guard against such changes. … Due to the sensitivity of a hash function’s output in relation to its input, changing the data in even the smallest way in a block, such as modifying a single character in the block’s attached file, will result in a completely different hash string. … Hence, data integrity can be checked by simply comparing the hash strings of a proposed blockchain under audit with a set of verified and correct hashes. Since each transaction is given its own block, precise determination of location and file that were corrupted are possible by simply finding the first block with an incorrect hash. Hence, storage of the desired and correct hashes is necessary, and we advocate for centralized and secured storage by the trusted regulator who will be performing the audit (see Supplementary Methods). Since only hash strings are required for the purpose of verifying integrity, the regulator need not allocate much hard disk space for the audit process. Verifying integrity can be done quickly as the regulator need only check for string equivalence, which is a quick and trivial process.

Here, an attack or defect has changed a stored document. As expected, doing so changes the document's block and by extension its hash value, thereby breaking the chain. The next section explains why this alone won't stop an attacker.

The last three sentences in the above quote deserve special attention. Tucked away in a convoluted, jargony paragraph describing an attack is a proposed solution with wide-ranging implications: distribute block hashes to the regulator. Before considering this countermeasure, it's important to understand the main flaw in the chain-breaking idea.

Chain Rewriting Attacks

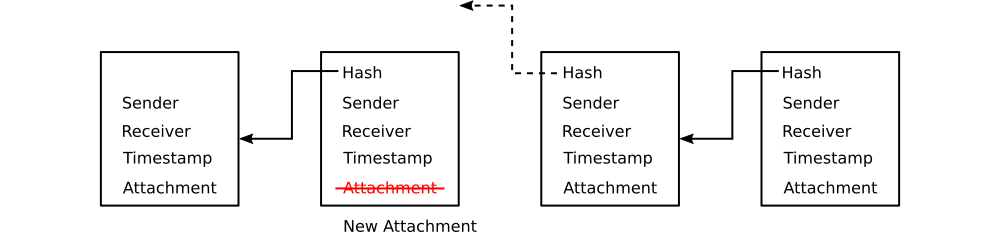

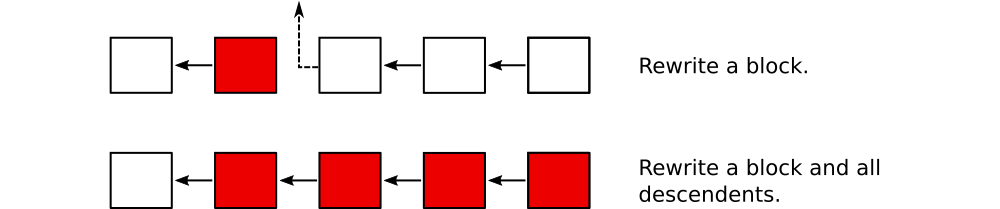

The UCSF paper assumes an attacker with trial sponsor privileges would only rewrite a single block, breaking the chain and thereby making the change obvious. However, it fails to explicitly treat the more likely attack that would leave an unbroken chain.

Consider what would happen if an attacker rewrote not just a block of interest, but all subsequent blocks as well. Merely rewriting one block would be easy to detect because it would leave the next block pointing to a non-existent parent, breaking the chain. Rewriting all subsequent blocks restores the chain to an unbroken state.

Recall that Bitcoin defends against this scenario by forcing attackers to expend resources to write valid blocks. By eliminating this requirement, the UCSF protocol exposes clinical trial data to trivial chain rewriting attacks. To be clear, the risk of data tampering is no greater under the UCSF protocol than if a block chain were not used. Rather, the point is that a bare block chain offers no technical protection against data modification attacks. To avoid breaking the chain, the attacker simply rewrites all subsequent blocks.

Clearly, a block chain by itself does nothing to ensure that data will be "immutable" or "tamper proof." Perpetuating this easily disproven claim in a high-profile forum such as Nature Communications has the potential to divert valuable resources from initiatives that can actually improve the security of clinical trial data. Worse, lulling clinicians and other non-technical users into a false sense of security about their data may encourage risky behavior.

Regulator to the Rescue

A chain rewriting attack creates a new unbroken chain by replacing not just one but many blocks. Each new block yields a new hash value, which can then be referenced by yet another new block. From parent to child, the old block hashes disappear with the old blocks, making fraud impossible to detect.

The promise of "immutable" and "tamper proof" data storage seems to be in jeopardy. Can it be saved?

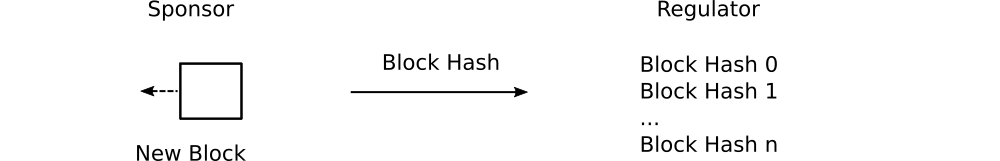

What if a separate, authoritative set of previously seen block hashes were maintained by the trial regulator? In the event of a chain rewriting attack, the discrepancy between block hashes reported by the sponsor to the regulator would be obvious.

This is the solution proposed by the UCSF team, which is repeated below:

… Hence, storage of the desired and correct hashes is necessary, and we advocate for centralized and secured storage by the trusted regulator who will be performing the audit (see Supplementary Methods). Since only hash strings are required for the purpose of verifying integrity, the regulator need not allocate much hard disk space for the audit process. Verifying integrity can be done quickly as the regulator need only check for string equivalence, which is a quick and trivial process.

In other words, the trial regulator (e.g., the US FDA) would maintain a list of valid block hashes for each clinical trial. Comparing this list with the blocks submitted from the trial sponsor would enable the detection of chain rewriting attacks.

At first glance, this appears to solve the problem. A deeper look, however, raises important questions.

Consider what would happen in the event of conflicting block hashes. Whose version should prevail - that of the sponsor or the regulator? An as yet unspecified protocol would need to be adopted for dispute resolution.

Keep in mind that the regulator just stores block hashes - not blocks themselves. The regulator could identify the first block that was rewritten, but the original contents of the block would remain unknown. A competent attack would likely start from the block that would reveal the least information about intent. That's likely to be the first one writable by the trial sponsor. In the event of a block rewriting attack, the sponsor and regulator would know that trial data had been forged, but neither the blocks that were replaced nor changes made would be identifiable.

Once again, the UCSF protocol would have failed to protect trial data from block rewriting attacks.

One way to solve this problem would be for the trial regulator to maintain a copy of every block rather than just the block hashes. In the event of a discrepancy, the version of the chain maintained by the regulator would be considered authoritative.

This approach raises the question of why the trial sponsor should even be involved in data maintenance at all. If the regulator maintains the authoritative version, maintaining a second copy merely increases complexity and risk without much to show for it. At the very least, a block chain becomes unnecessary.

In the interest of efficiency and accuracy, the regulator would eventually absorb all data management responsibilities from the trial sponsor.

Ironically, this situation places the regulator in exactly the same predicament that the trial sponsor was in. How will valuable clinical trial data be protected from forgery and corruption?

The regulator might consider adopting the UCSF protocol. Notice, however, that in this case there is no higher authority with which block hashes can be deposited. The buck stops with the regulator. Actually, there might be a higher authority, but that's an article for another time.

So this is where the story ends — with a block chain that no savvy observer would ever describe as "immutable" or "tamper proof." If this exercise ultimately ends in a futile return to the status quo, why not build a system that will deliver real security in the first place rather than security theatre?

Conclusions

Improving the security of sensitive scientific data is a worthwhile goal. Hash-based audit trails like the one proposed in the UCSF paper might offer some benefit in very limited cases. But claims of immutable and tamper proof data protection should be viewed with great skepticism. Bitcoin solved a very specific problem through a brilliant combination of existing technologies and economic incentives. Cherry picking Bitcoin's technologies neutralizes its hard-won security guarantees.

Before committing valuable resources to a block chain project, consider discussing these questions with your team:

- What specific security threats will the use of a block chain defend against?

- What alternatives exist for countering these threats?

- How will block rewriting attacks be addressed?

- How will legitimate modification of data be distinguished from attacks?

- In what specific ways will security be compromised by eliminating the block chain from this project?

- What trusted third parties does this block chain protocol require?