The SMILES Substructure Search Fallacy

Meet Jane, a Web developer tasked with implementing structure search on a customer website. Jane has just learned that small organic molecules can be represented by short text strings called SMILES. Relieved that the structure search problem isn't nearly as complicated as it first sounded, Jane tells her customer not to worry — structure search will be ready ahead of schedule and within budget.

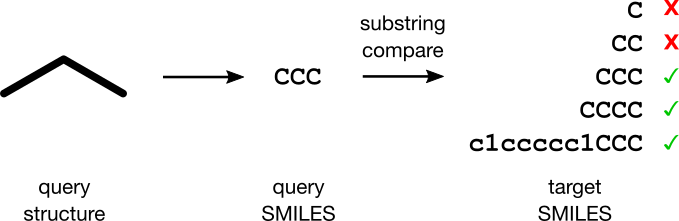

Jane's plan is simple. A SMILES encodes a molecule, allowing her to transform the substructure search problem into a substring matching problem. When a user submits a substructure request, Jane's software will first transform the query structure into a SMILES query string. For each target SMILES in the collection, the software will attempt a substring match against the query string. Returning the hits to the user completes the search. Voilà!

Jane doesn't know it yet, but she's about to have one angry customer. This article explains why.

For the Cheminformaticians

Those who have worked in cheminformatics before may consider Jane's idea a non-starter and wonder how anyone could seriously consider it. Nevertheless, over the last few years I have witnessed multiple instances of web development teams thinking exactly like Jane. Often, this approach is the first thing developers unfamiliar with cheminformatics will reach for. It's far from obvious to a novice why it can't work.

Molecular Graphs

A molecule can be thought of as an undirected simple graph, meaning that edges have no directionality and can never join the same node, nor can two nodes be joined by more than one edge. In a molecular graph, nodes map to atoms and edges map to bonds, more or less in a 1:1 fashion.

Dealing with graphs is much more complicated than dealing with common data structures such as strings, arrays, and hashes. For one thing, graph are multifaceted objects when properly implemented. Their memory requirements are high and their APIs must support several vital operations. Whereas linear data structures can be iterated from start to end deterministically, graphs must be traversed. The complexity of these traversals dwarfs those for strings, arrays, and hashes.

Most importantly, graphs can not be compared for full or partial equality using the same linear procedures as strings, hashes, and arrays.

Subgraph Isomorphism and Structure Search

It's often necessary to determine whether a query graph is embedded within a target graph. This well-known problem goes by the name subgraph isomorphism.

There's a clear correspondence between the subgraph isomorphism problem and the substructure search problem. As a result, substructure search inherits all of the computational properties of subgraph isomorphism. The most notable of these is complexity.

The brute force "atom-by-atom search" strategy boils down to considering every possible way of mapping query nodes to target nodes. Start by picking one random node each from the query and target graphs. Test for a match by, for example, looking at atom labels. If there's no match, choose a different target node and try again. If there is a match, pick a neighbor of the previous query node and a neighbor of the last matched target node. On reaching a dead end, trace back to your last branch point and consider an alternative. Keep going until either: (1) you map every query node onto one target node; or (2) you run out of possibilities to try. Specifics vary by procedure, but all subgraph isomorphism algorithms follow a similar script.

For these reasons, implementing substructure search from scratch is non-trivial. Not only are the algorithms themselves complex, but inherent computational properties ensure that memory and time performance will remain constant concerns.

Why Substring Search ≠ Substructure Search

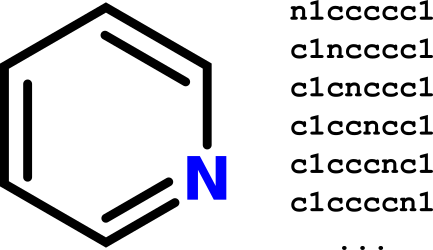

To understand why Jane's plan to use substring search as a proxy for substructure search won't work, consider a counterexample. Pyridine can be represented using the SMILES:

n1ccccc1.

But pyridine can also be represented by five other equivalent SMILES strings:

c1ncccc1c1cnccc1c1ccncc1c1cccnc1c1ccccn1

SMILES are generated from a depth-first traversal of the corresponding molecular graph. Different starting atoms and different neighbor atom traversals will yield different SMILES as a result. The presence of cycles only adds fuel to the fire. From this perspective it's clear why a simple linear substring comparison should be expected to fail most of the time.

It gets worse. SMILES supports multiple encoding schemes for double bonds. The aromatic notation for pyridine is one form. Another form uses capital letters and the equals character (=) to denote a double bond. Six possibilities are:

N1=CC=CC=C1C1=NC=CC=C1C1=CN=CC=C1C1=CC=NC=C1C1=CC=CN=C1C1=CC=CC=N1

It gets worse still. Single bonds are optional, meaning that N1=CC=CC=C1 is equivalent to N-1=C-C=C-C=C-1. Likewise, aromatic bonds are optional, meaning that c1ncccc1 is equivalent to c:1:n:c:c:c:c:1. Nor do the problems end there. Notice how obviously wrong the substring matching approach becomes with a good counterexample. Also consider the number of simple cases that will work perfectly.

No matter how hard Jane tries to patch her substring search method, another special case will rear its head to mess things up. If she has little experience with chemistry or cheminformatics (as is common among web developers), Jane may not fully appreciate the scope of the problem, making the incremental approach of trying to patch the previous iteration attractive. In this way, Jane can be lead, step by painful step, down a path destined to result in delays, cost overruns, and tarnished reputations.

SMILES and Exact Structure Search

Hopefully you are now convinced that naive substring search will never work as a proxy for substructure search. If you're not, chances are very good that you don't yet understand the problem. Keep thinking about it until the flaws become crystal clear.

But what about exact structure search? Can SMILES uniquely encode a molecular structure and thereby offer a fast method to compare two molecules for exact equality? This may work, but not without considerable effort. A molecule can be expressed as a unique ("canonical") SMILES, but only with the assistance of sophisticated (and often expensive) software. A more practical option is to use InChI. InChI is a unique molecular identifier generated by an open source software package distributed by the international standards body IUPAC.

Integration

Although implementing substructure search from scratch is very difficult, many libraries have been created to solve the problem. Some of them are open source. They tend to run on a back end, and as such require the installation of binaries and in most cases the alteration of database schema and/or software.

Ease of integration for any particular package depends largely on the underlying web stack. To streamline integration, my company offers ChemServer, a simple substructure search engine suitable for collections of up to around 10,000 in size. For larger collections, my company offers consulting services.

Conclusion

Text matching on SMILES strings seems like a natural, simple solution to the substructure search problem. But this is a mirage. The futility of this approach may only become apparent after weeks or even months of effort. Regardless of the specific implementation, any robust solution must compare molecules as graphs.