The Maximum Matching Problem

Graph theory plays a central role in cheminformatics, computational chemistry, and numerous fields outside of chemistry. This article introduces a well-known problem in graph theory, and outlines a solution.

Matching in a Nutshell

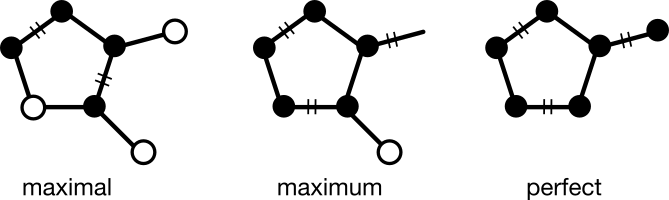

A matching (M) is a subgraph in which no two edges share a common node. Alternatively, a matching can be thought of as a subgraph in which all nodes are of degree one. Based on this definition, three broad matching categories can be defined:

- Maximal. No additional edges can be added.

- Maximum. The most possible edges have been added.

- Perfect. All nodes have been added. This kind of matching is sometimes called a "1-factor."

A matching can be maximal but nevertheless not maximum, depending on the order in which nodes were matched. A perfect matching will always be a maximum matching because the addition of any new edge would cause two previously-matched nodes to be of degree two. A graph may have multiple maximum or perfect matchings.

Nodes and edges can be classified as matched or unmatched. A matched node or edge (solid black circle and hashed line, respectively) appears in both parent graph G and matching M. Conversely, an unmatched node or edge (open circle or unhashed line, respectively) appears in the parent graph G but not in matching M. Matched and unmatched features are usually referred to as being "covered" or "exposed," respectively. A matching algorithm attempts to iteratively assign unmatched nodes and edges to a matching.

The maximum matching problem ask for a maximum matching given any graph. This article only considers maximum matching of unweighted graphs (edges have no value). Such matchings are also known as as "maximum cardinality matchings."

Applications: Kekulization and Tautomerization

Maximum matching directly relates to the chemical concept of kekulization. In kekulization, alternating double bonds are assigned to a molecule in which only a sigma bond framework and atomic hydrogen counts are given. The presence of multiple resonance structures for the same molecule corresponds to the ability of a graph to contain multiple maximal matchings. "Pushing" electrons to reveal new resonance structures also yields a new matching based on an existing one.

Although many situations call for kekulization, the most common arises from depiction of a molecule represented by a line notation such as SMILES or InChI. As such, most cheminformatics toolkits require kekulization and therefore must solve the maximum matching problem.

Matching also finds application to the closely-related process of tautomerization. For example, an algorithm reported by Sayle and Delany yields a canonical tautomer through the iterative construction of a matching-constrained subgraph.

An excellent overview of matching, kekulization, and tautomerization is available in John May's Dissertation.

The number of matchings in a chemical graph might be expected to yield information about energetics, especially for aromatic systems. One of the earliest explorations of this idea came by way of the Hisoya Index, the number of non-empty matchings plus one. Later studies used matching polynomials to predict magnetic resonance and topological resonance energies.

Maximum matching also finds application in a variety of scheduling problems such as at schools, hospitals, and in transportation networks.

A Naive Matching Algorithm

A naive approach to finding a maximal matching can be outlined as follows. Traverse the edges of a graph in depth-first order starting from an arbitrary node. Greedily match the first pair of nodes, and all possible node pairs during the traversal. On completing a traversal, record the matching and its edge count ("cardinality"). Then, backtrack to the last branch to find a new matching. Continue until all matchings and their cardinalities have been found.

This algorithm, although simple, is quite inefficient. It is equivalent to finding all paths through a molecule, a problem known for its lack of efficient algorithms.

Fortunately, it's possible to do much better.

Berge's Lemma and Augmenting Paths

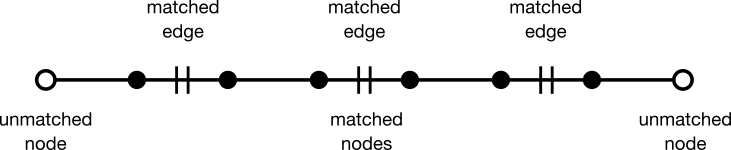

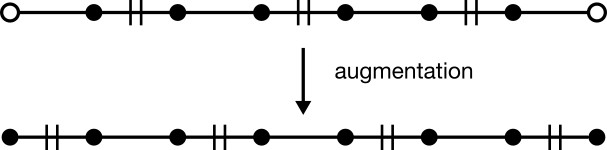

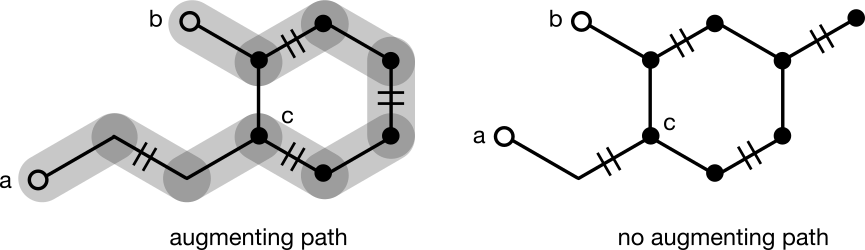

Berge's Lemma states that a matching is maximum if and only if it has no augmenting path. An augmenting path is an acyclic (simple) path through a graph beginning and ending with an unmatched node. The edges along the path are alternately matched and unmatched. The number of edges in an augmenting path must always be odd.

Given any augmenting path, a matching with one more edge can be generated. To do so, unmatch every matched edge while simultaneously matching every matched edge. This operation is known as "augmentation." In the language of sets, the operation over edges is called "symmetric difference."

Augmentation does two useful things. First, it adds one more edge to the matching. Second, it does so without disrupting matchings exterior to the path. That second feature is a necessary condition for the first, and ensures that previous matching will always be preserved after augmentation. In other words, a matching is guaranteed to grow by one edge for as long as an augmenting path can be found.

Using augmentation and Berge's Lemma, the naive algorithm can be reworked:

- Create a greedy matching M using, for example, a non-backtracking depth-first search.

- Pick an unmatched node a.

- Starting from a, follow alternating unmatched/matched edges until encountering unmatched node b. The result is augmenting path P.

- Augment M with P.

- Repeat until no augmenting path P can be found.

Maximum Matching in Bipartite Graphs

The new algorithm works perfectly for any graph, provided there are no cycles of odd node count. In other words, the graph must be "bipartite". Bipartite graphs work so well, in fact, that they will often terminate with a maximum matching after a greedy match.

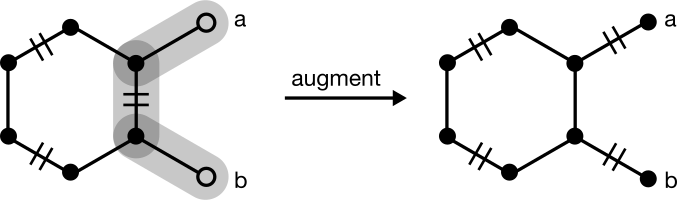

In some cases, however, the greedy match will require augmentation. Consider one that starts from the neighbor of a terminal node:

Another matching exists with one more edge, so this matching is not maximal. To find it, pick up the algorithm at Step (2), choosing the unmatched degree one node a. An augmenting path can be found with a depth-first search to node b. Augmentation yields a maximum and perfect matching given that no nodes or edges remain unmatched.

Bipartite graphs may represent most, if not all input graphs for a given collection. For example, most kekulization requests will involve a bipartite molecular graph such as a benzene or naphthalene analog. However, this restriction is unlikely to hold over every collection. Sooner or later a graph with an odd cycle will be encountered. Handling such cases is what makes maximum matching the complex problem that it is.

It might be tempting to apply shortcuts at this stage. For example, we might notice that a perfect matching (benzenoid resonance form) only exists for molecular graphs containing an even node count. However, this is a necessary but not sufficient condition. It's quite easy to find graphs with even node count but no perfect matching. See, for example, the odd star graphs.

Cycle Traversal

An even cycle presents no particular challenge to finding an augmenting path. To understand why, consider trying to uncover an augmenting path between nodes a and b separated by a six-membered cycle. Traversal eventually ends up at the base of the cycle, node c. If a neighbor of c exists along a matched edge, that neighbor will be traversed first, ultimately leading to node b. If no matched edge exists, either branch will be followed and b will never be reached. This is expected because no augmenting paths to b exist. The same analysis applies regardless of how a traversal enters an even-membered cycle.

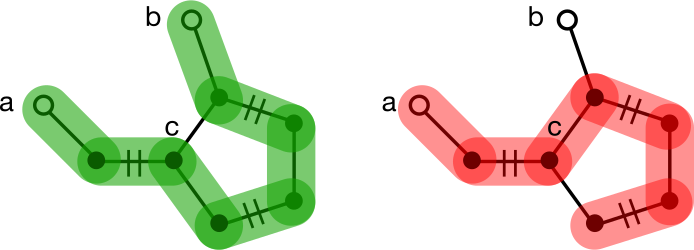

Odd cycles are a different story. Consider trying to uncover an augmenting path between nodes a and b separated by a five-membered cycle. Traversal eventually ends up at the base of the cycle, node c. If a neighbor of c exists along a matched edge, that neighbor will be traversed first, ultimately leading to node b. If no matched node exists, either branch can be followed, but only one will discover the augmenting path to b. It's equally likely for either branch to be chosen, so the traversal will fail to augment the matching about half the time.

Matching on general graphs requires a way to deal with odd cycles.

Blossoms

In 1965 Jack Edmonds proposed the first efficient approach to the problem of augmentation across odd cycles. The key step of his "blossom" algorithm is the collapse of the odd cycle (the "blossom") into a single node, which is then traversed as usual. The blossom is then "lifted" to reveal the augmenting path.

Since 1965, a number of algorithms capable of finding maximum matchings on general graphs have been described. The most efficient of these was published by Micali and Variani.

Conclusion

Maximum matchings find their way into a few important cheminformatics and computational chemistry contexts. To the untrained observer, the maximum matching problem might appear trivial. Indeed, in the case of bipartite graphs it is. However, the need to deal with odd cycles for general graphs vastly increases the complexity of the solution. This article doesn't describe such a solution in detail, but a future article will.