The Language of Organic Chemistry

Molecular structures are sometimes thought of a possessing language-like properties. Smaller units (atoms and bonds) are assembled into larger units according to well-defined rules of syntax and semantics. These smaller units form molecules, molecules aggregate together into supramolecular assemblies, and so on.

Until a few years ago, however, no attempt was made to apply the rapidly-developing quantitative tools of computational linguistics to study one of science's oldest special-purpose languages. This article discusses the first study to do so.

Computational Linguistics for Organic Chemical Structures

A 2014 paper from Northwestern University and the Polish Academy of Sciences explores mathematical relationships between molecular structures and spoken languages. The study first develops the concept of a chemical word. Then, this concept is applied to the problems of symmetry perception and retrosynthesis.

Zipf's Law

The authors begin by noting the wide applicability of Zipf's Law to spoken languages. This empirical relationship states that the frequency with which a word will occur within a corpus is inversely proportional to its rank. For example, the second ranked word in terms of occurrence will appear half as often as the top word. Likewise, the third ranked word will appear 1/3 as often as the top ranked word. And so on. Not only does Zipf's Law work across languages, it works in domains far removed from languages. Such relationships are broadly known as "power laws."

Given its importance for spoken languages, attempts to treat organic chemical structures linguistically should be compatible with Zipf's Law.

Functional Groups Are Not the Answer

If organic chemistry is a language, what are its words?

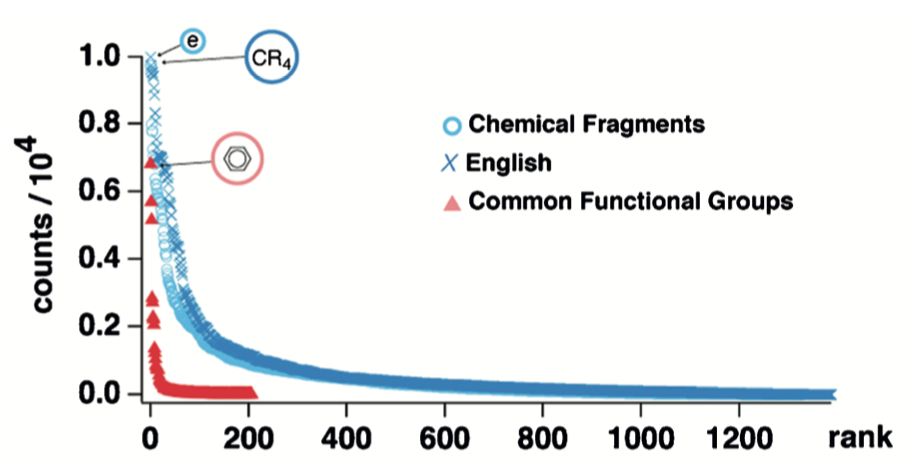

One obvious answer is "functional groups." This well-known concept, corresponding to a reactive assembly of atoms, serves as the foundation on which the art and science of organic synthesis have been learned for decades. If functional groups were organic chemistry's words, then the frequency of functional group appearances should follow Zipf's law.

To test this idea the authors applied the following procedure:

- Identify a collection of organic molecules.

- Identify a functional group dictionary.

- Using the dictionary, count the number of occurrences of each functional group in the molecule collection.

- For each functional group, plot rank vs. count on logarithmic axes.

This procedure led to a plot that deviated noticeably from the relationship obtained for English text. Unfortunately, this plot was only reported on linear axes, not the double log scale customarily used. In addition to the English/functional group comparison, the plot above contains a series (blue circles) composed of data generated from the more sophisticated approach discussed in the next section.

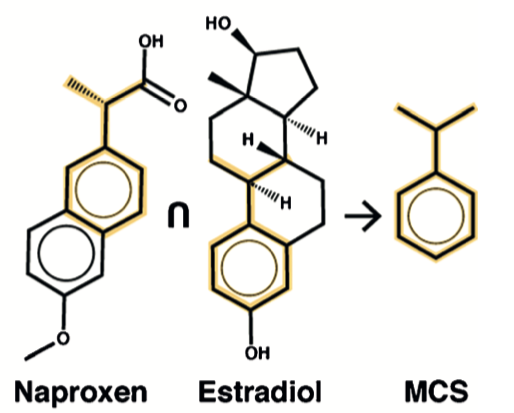

Maximum Common Substructure

Word counts are just one way to analyze texts. An alternative method uses longest common substring (LCS). An LCS is the longest continuous run of common characters found within two sentences. For some pairs of sentences, the LCS may consist of just a single character. For other pairs, words and even entire phrases may appear in the LCS. Dictionaries compiled from LCSs show power law distributions similar to word-based dictionaries.

The authors note that LCS roughly translates to the chemical concept of maximum common substructure (MCS). An MCS is obtained by finding the largest substructure shared between two molecules. This procedure is computationally-expensive.

To test the idea that MCS could define a unit obeying a power law distribution, an adaptation of the original procedure was used:

- Obtain a collection of organic molecules.

- For each pair of molecules, compute an MCS, adding the result to a dictionary.

- Using the dictionary, count the number of occurrences of each MCS in every molecule. A single molecule may contain multiple MCSs.

- For each MCS, plot rank vs count on logarithmic axes.

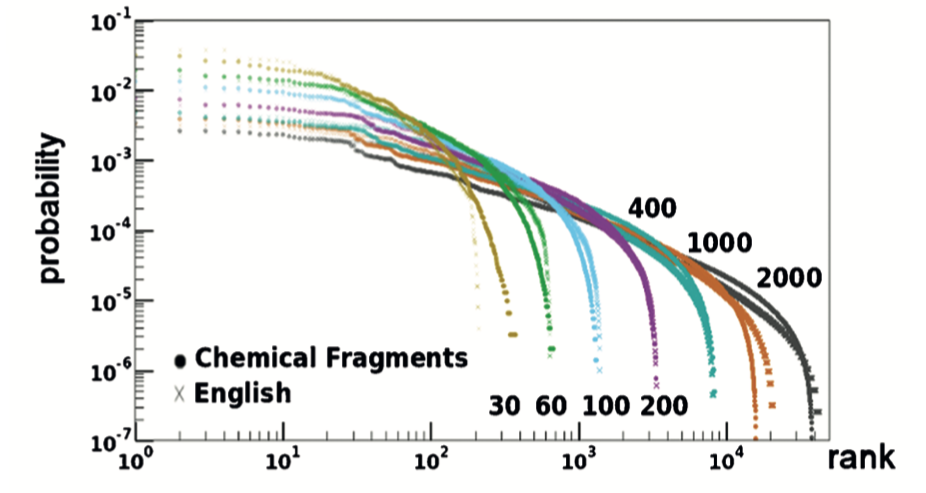

This procedure yielded the following plot:

This plot includes the rank vs. probability curves for seven MCS fragments (dots) and the correspondingly-ranked and identically colored LCS (crosses). The similarity between English, a spoken language, and chemical structures, a language grounded in graph theory and natural science, is striking.

TF-IDF Scoring

The more highly-represented a word across sentences or documents, the less information it tends to carry. For example, consider the relative information content of two words, "the" and "dentist," both of which appear in the same sentence. The less common word conveys more information due to its rarity.

We can account for these differences with a weighted scoring system known as term frequency-inverse document frequency (TF-IDF):

where tf is the count of words in a sentence and idf is a weight that decreases as the number of occurrences across documents increases. idf is usually expressed as a logarithm, for example, the negative log of the fraction of documents containing the word. In this way, TF-IDF ensures that words that rarely appear within a corpus will receive a higher score when found within a member text.

The authors developed expressions for tf and idf that can be used with MCS fragment counts. For a given molecule, tf is computed as:

where Fi is the count for fragment i and Fmol is the total number of fragments found in the molecule. For example, if a molecule contains 25 different fragments, 5 of which are acetyl, then Fi for this fragment equals 5/25, or 0.2.

Similarly, idf is computed as:

where Mi is the number of molecules containing MCS fragment i and Mdict is the number of MCS fragments in the dictionary.

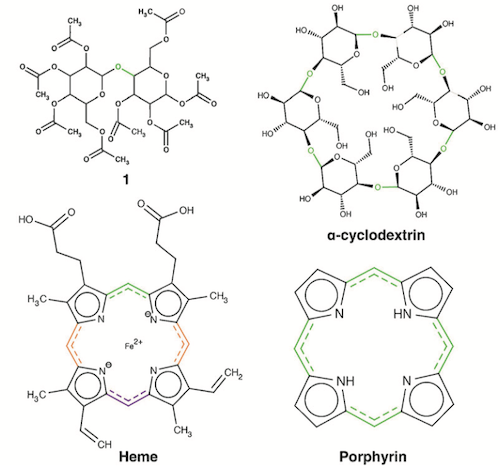

Bond Information Content and Score

Given that the words of a sentence vary in the quantity of information they carry, does the same also apply to the bonds (or atoms) of a molecule? If so, of what practical or theoretical consequence might this variability be?

Answering these questions requires a linguistic bond metric. The discussion above suggests starting with the TF-IDF fragment score. From there, a number of scoring functions are feasible. The authors chose one consisting of the average TF-IDF score for each fragment the bond participates in:

where m is the number of fragments in the global MCS dictionary.

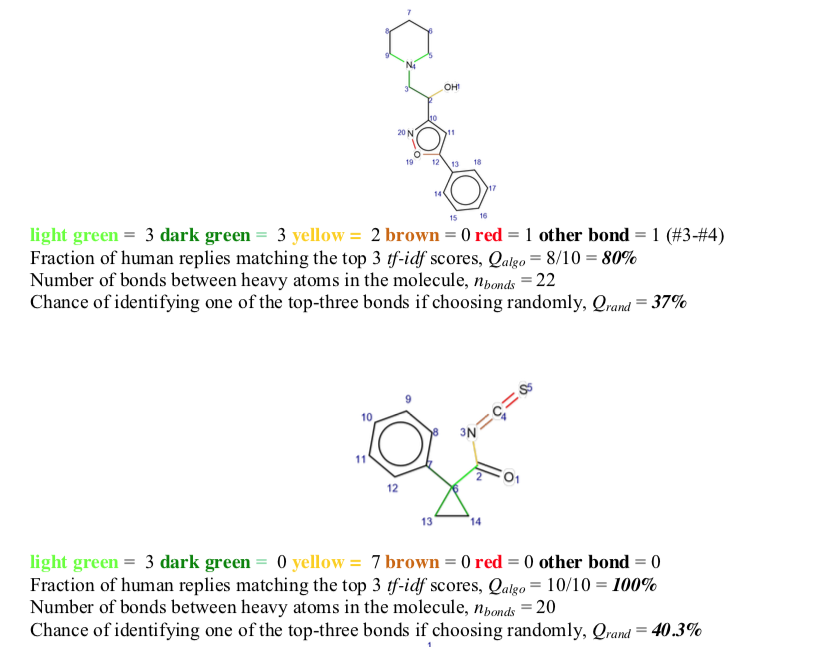

Visual inspection of highly-scored bonds (light green > dark green > yellow> red ~ brown) revealed many of them to be associated with symmetry elements. This observation raised the question of what role highly-scored bonds might play elsewhere.

Bond Score and Retrosynthesis

Many forms of chemical computation predict bond properties, one of the oldest of which attempts to identify strategic retrosynthetic bonds. Given that these bonds often join two relatively abundant fragments, and may be associated with important symmetry elements, the application of linguistic bond scoring to retrosynthesis was examined.

68 molecules from the Dictionary of Natural Products were selected. Bonds were color coded according to their linguistic score as described above (light green > dark green > yellow > brown ~ red). These annotated 2D structures were then given to a panel of ten Ph.D. organic chemists for evaluation. In 75% of cases, linguistic bond scores were chosen preferentially over random color coding. Success did, however, depend on the molecule's bond count. Best results were obtained for molecules with more than 19 bonds.

The role of human experts in this study is worth considering in detail. The Supporting Information explains the procedure:

A quiz was designed to test the quality of the tf-idf predictions as to which bonds are the most suitable loci for retrosynthetic disconnection. 68 molecules chosen at random from a natural product database (CRC Dictionary of Natural Products, http://dnp.chemnetbase.com/tour/) were analyzed and all bonds (between non-H atoms) in these molecules were automatically scored according to the tf-idf scores. The top-three ranking bonds were colored, respectively, light green, dark green, and yellow. The two lowest scoring bonds were colored brown and red. These molecules were inspected by Nchem = 10 (9 on some molecules) Ph.D. level (and above) organic chemists from the Institute of Organic Chemistry of the Polish Academy of Sciences in Warsaw. Without any prior explanation of the color coding, each chemist was asked to independently choose the bond that would be his/her choice for disconnection (+/- potential protection/deprotection); if none of the colored bonds matched the choice, the chemists were asked to specify another bond (atom#-atom#) that they would suggest cutting. These predictions by expert chemists were the true positives against which the performance of the algorithm was compared. … [my emphasis]

In other words, the 2D structures given to human experts contained color-coded bonds — but why? To minimize bias, it seems reasonable to give human experts 2D structures devoid of special markings. Beyond the issues of this particular study lies the broader question of why human experts are required at all to establish ground truth for strategic bond disconnection. A fully-automated system would allow broader evaluation and better reproducibility.

The authors note that some highly contraindicated bonds were identified for disconnection (e.g., phenyl C-C). One factor that could be at play is that the Dictionary of Natural Products contains an unusually-high number of benzene ring-containing molecules relative to the database from which the fragment dictionary was compiled (Beilstein). This could result in higher than justified fragment score for the aromatic rings that are present, thus boosting the score for bonds within these groups.

Aside from minimum bond count, reliance on human-based ground truth, and sensitivity to test set composition, linguistic bond scoring faces another limitation when applied to retrosynthesis: only single bond disconnections are possible. Disconnections whose reverse sense leads to multi-center reactions such as Diels-Alder, epoxidation, and dihydroxylyation won't be detected.

Extension & Application

The work described here is an island of sorts. A 2018 paper described the application of MCS-based linguistic analysis to the evaluation of molecular diversity. Beyond this, no extensions or applications appear to have been published, despite several viable opportunities. Two factors may be at play. For one, human subject matter experts are required to test retrosynthetic bond scorings. This requirement vastly complicates the evaluation of predictive models. For another MCS, upon which the linguistic analysis depends, is a computation for which no polynomial-time algorithms are known. Obtaining large fragment dictionaries could be challenging, although perhaps not prohibitively so. The work has been cited in a few studies noting its theoretical importance as a bridge between computational linguistics and chemistry. As can be seen here, however, that connection depends on the procedure used to generate the fragment dictionary.

Conclusion

An array of powerful tools awaits problems that can be recast in terms of computational linguistics. But as the work highlighted here shows, finding the right interface and working at scale could prove tricky. Nevertheless, maximum common substructure has been established as a linguistic unit in organic chemistry, and as such could offer a roadmap for travellers wanting to make the journey.