Distributed Chemistry

Distributed systems pervade modern computer technology. Examples include multi-core CPUs, GPUs, computer clusters, and the Internet itself. Although many forms of distributed computing have been developed, their main purpose is to increase the utility of individual resources through cooperation, often involving some form of parallelization. For example, a large computational job can broken down into smaller jobs, which are then distributed among semi-independent workers. Each worker performs its task, then returns the result over a communication channel. Assembling the responses yields the final result.

What specific roles could a distributed, fully-automated system play in chemical research? That's the topic of a recent study from the Cronin group.

Meet the Robots

The Cronin system consists of two or more chemistry processing units ("ChemPUs") connected via a computer network. Each ChemPU solves part of a larger chemical problem while in communication with the other.

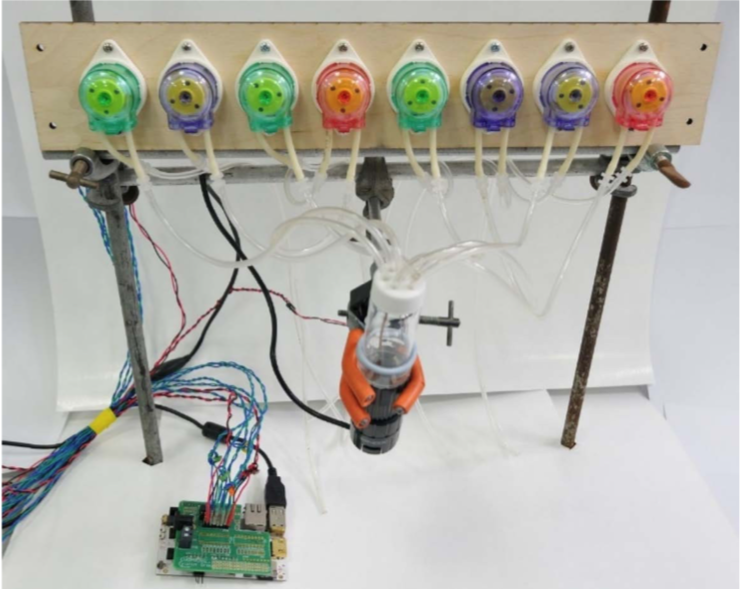

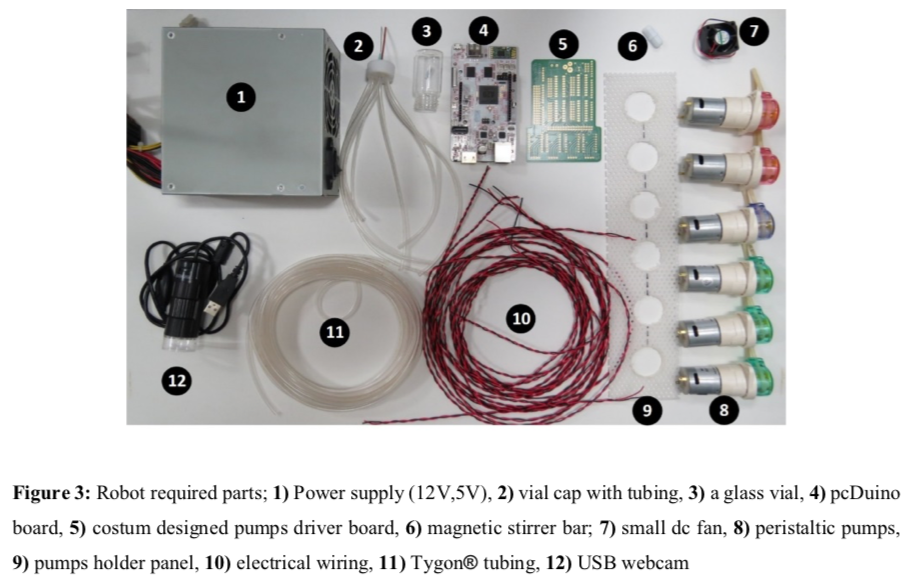

The current ChemPU implementation is built from low-cost computer hardware (pcDuino3, power supply), open source software (python, opencv, gpio), commodity lab equipment (peristaltic pumps, Tygon tubing, 14 mL glass vials) and sensors (webcams). The paper claims that a ChemPU can be assembled in a few hours.

ChemPUs communicate over a computer network. Peer-to-peer communication is in principle possible, but this requires custom software and significant effort to implement. To economize, the team explored a far simpler communication protocol running over Twitter. Another study used a custom client-server protocol to build and maintain global state.

Why?

The first mass marketed computers lacked a modem as standard equipment. Early adopters (mainly techie hobbyists) found enough value in an isolated computer that the thought of connecting to other computers occurred much less often than it might seem. It took years to build a sufficiently large online user base that bulletin board services and FidoNet, primordial versions of today's Web, began to emerge.

In that spirit, it may not be clear today why two or more ChemPUs working together would be useful. The reasons, much like the motivations behind distributed computing, come down to improved resource use. Two ChemPUs can work in parallel on the same problem, returning an answer in less time than it would take one working in isolation. Otherwise idle equipment can be put to use as needed. Costs can be distributed among multiple centers. Problems of increasing complexity can be scaled up by adding more units.

Effective use of a distributed system requires some care in designing protocols. The Cronin team considered three prototypical ChemPU strategies:

- Random. Each ChemPu has no memory of what experiments it (or the others) previously ran. This poor choices is probably included for comparison only.

- Individual. Each ChemPU remembers its own experiments, but not those of the other ChemPUs. Duplication of effort will occur, requiring more experiments.

- Collaborative. Each ChemPU remembers its own experiments and those of other ChemPUs. Any given experiment will only be run once across the network. If only one ChemPu is on a network, then the Collaborative approach simplifies to the Indivudal approach.

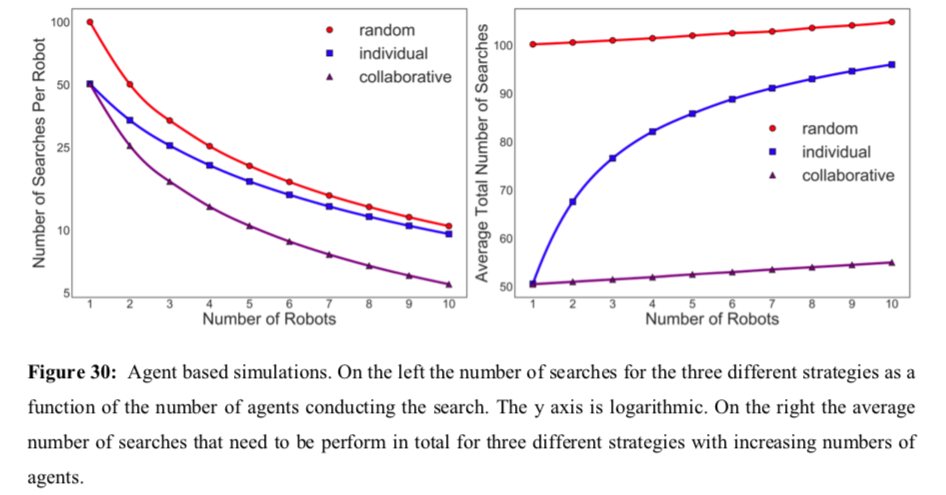

Plotting the number of searches per robot against the number of robots illustrates how each additional robot needs to perform fewer experiments to achieve the same outcome.

The plot on the left compares the number of searches per ChemPU, normalized to the worst case of random search. Consider the case of one ChemPU operating in isolation. The individual strategy yields a 50% reduction in the number of experiments per unit compared to a random strategy. As expected, increasing the number of ChemPUs to two leads to fewer per-unit experiments for the collaborative strategy compared to the individual. Unfortunately, the mathematical model was not discussed in the paper.

Better Optimization through Parallelization

Some chemistry problems inherently resist parallelization. For example, a linear organic synthesis requires as input a starting material made in previous steps. Throwing more automated resources at such a problem will not increase efficiency. More problematic, however, is the need to physically transport samples. A parallelizable problem in which only data is exchanged is the best fit for a ChemPU network.

For this reason the Cronin group chose its model studies carefully. There were three, all of which could fall into the general category of "optimization."

Structure-Property Optimization

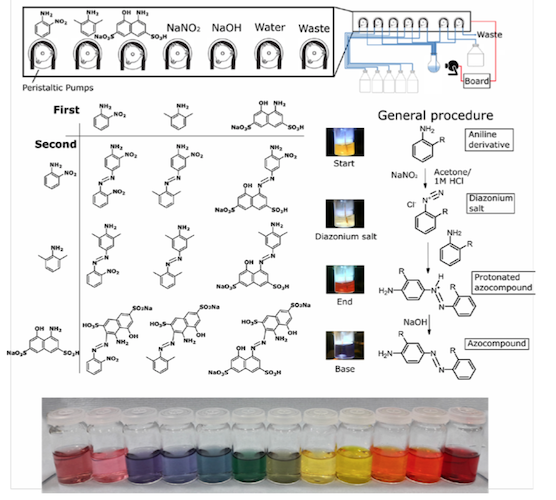

Azo dyes are made by reacting an aniline with a diazonium salt in acidic medium. Using this process as a model for structure-property optimization, where color is the property of interest, a study with two ChemPUs working collaboratively was performed. On completion of an experiment, a ChemPU tweeted the color it obtained, encoded as an RGB value recorded from an onboard camera. Each robot updated its own internal copy of a data matrix based on the real-time Twitter feed of the other.

In an intriguing twist on this process, the authors investigated an alternative protocol based on the game Hex. A server running a simulation linked two ChemPUs together as each attempted to play the game by mixing reagents, merging information on winning strategies into the next round. The main advantage of casting the optimization in this particular form appears to be access to a number of existing Hex simulators.

Synthesis Optimization

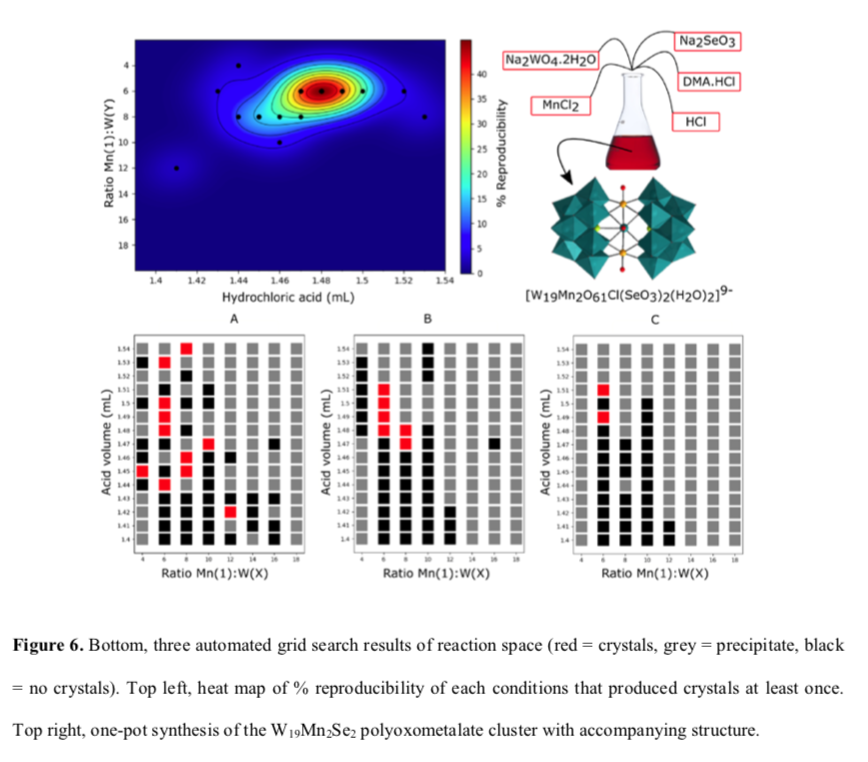

Synthesis optimization is in many ways an ideal candidate for lab automation. It's tedious to perform, not in general well-modeled theoretically, and therefore highly empirical. The Cronin group used the synthesis of tungsten polyoxometallate clusters as a model for the kind of synthetic optimization that could be performed by a network of ChemPUs working collaboratively.

A network of two ChemPUs varied reaction pH and metal ratio, using the formation of crystals (automatically monitored by webcam) as an endpoint. Here the goal wasn't to find novel parameters, but rather to confirm the reproducibility of published parameters.

Chemical Synchronization

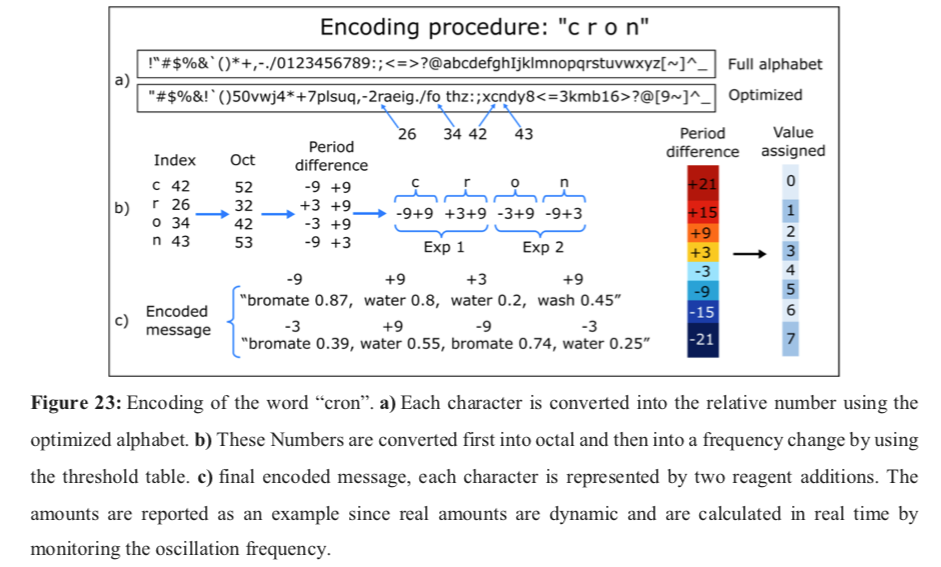

One of the most intriguing aspects of the Cronin system is how it opens up new areas for study. Consider the problem of synchronizing two instances of the same chemical oscillator. In particular, the team's goal was to get two ChemPUs to end up with the same frequency for their individual instances of the Belousov-Zhabotinsky (BZ) oscillator. Here, ChemPUs were instructed to follow a leader-follower protocol. One ChemPu would establish an oscillation frequency. Observing this over the network, the other ChemPU attempted to replicate the frequency through real-time image processing and a computer-controlled algorithm. The approach yielded such precision (90 minutes with ± 2 second error) that the authors were able to encode messages by modulating the oscillator frequency.

Although this study doesn't appear to have much practical utility, it does point to a mode of distributed chemistry that's hard to achieve in any other way. It also nicely demonstrates a method whereby a ChemFP can adapt its operation to prevailing network conditions under purely machine control.

Conclusion

Lab automation is a good match for any problem that can be reduced to a parallelizable search through some well-understood space. For years, the majority of such efforts have centered on analytical chemistry and biochemistry. Although a network of ChemPU units optimizing azo dye colors is a far cry from a graduate student optimizing a palladium-coupling reaction, it's not that far off. The availability of platforms like ChemPU, built from cheap, off-the-shelf components, infinitely hackable, and under the control of potentially very sophisticated software, could help transform those areas of experimental chemistry that have so far resisted automation.

"Chemical Encoding"

"Chemical Encoding"