Computing Extended Connectivity Fingerprints

A fingerprint is a useful kind of low-resolution molecular representation. Fingerprints come in a many forms and have been applied to a diverse range of problems over the last few decades. Extended Connectivity Fingerprints (ECFPs, or "Circular Fingerprints") offer a number of advantages over other schemes. This article describes the structure and generation of ECFPs at a high level.

ECFPs were first introduced in 2000 with the release of Pipeline Pilot. A 2010 paper by Rogers and Hahn described the generation of ECFPs in detail.

A Little About the Morgan Algorithm and SMILES Canonicalization

The core idea behind ECFPs traces its origin to the Morgan algorithm. This algorithm seeks to assign a unique, sequential atom numbering for any given molecule. Unique atom numbering underpins all widely-used methods for molecule identification, including those used by InChI and the CAS Registry.

The Morgan algorithm takes place in two phases, the first of which is the enumeration of all atom assignments (numberings) obeying the following rules:

- A random atom is selected and labeled "1".

- Each unlabeled neighbor of Atom 1 is iterated in random order and assigned the next highest available number ("2", "3", and so on).

- Each newly-labeled atom is iterated in order of its label, and its neighbors are numbered according to Step (2).

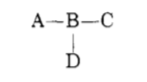

This procedure continues until all atoms have been labeled. The result is a set of atom assignments, each one containing a unique numbering. For example, the molecule:

yields the following 12 assignments:

The second phase of the Morgan algorithm iteratively eliminates assignments until only one remains. The key element of this process is a procedure in which each atom's connectivity is perceived at ever greater distance. First, each atom is assigned an initial "connectivity value" equal to the number of heavy atoms attached to it. Subsequent iterations replace the previous connectivity value with a new one computed as the sum of neighbor connectivity values. The process terminates when the number of unique connectivity values decreases from one round to the next. The connectivity values in the final round are used to eliminate assignments and ultimately arrive at a unique atom numbering for a given molecule.

A similar procedure is used to generate unique SMILES via the CANGEN algorithm. In this case, however, the initial value assigned to each atom accounts for the following atomic invariants:

- number of heavy atom connections;

- number of non-hydrogen bonds;

- atomic number;

- sign of charge;

- absolute charge;

- number of attached hydrogens.

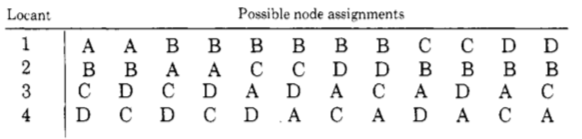

These properties can be conveniently encoded as integer values. In this article these values will be referred to as "atom identifiers," although the term used in the CANGEN paper is "invariant." For example, the atoms of pentane can be encoded according to the following scheme:

The next phase of the CANGEN algorithm follows a pattern analogous to the second stage of the Morgan algorithm. The initial integer identifiers are iteratively replaced with new ones derived from neighbor identifiers until a stable assignment of labels results.

Extended Connectivity

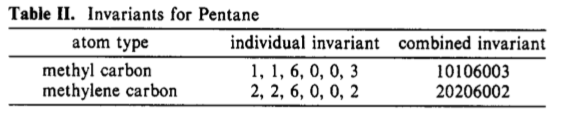

The terms "extended connectivity" and "circular" hint at an underlying connection between ECFPs, the CANGEN algorithm, and the Morgan algorithm. Namely, each atom in a molecule can be viewed as the center of a radius of perception or "orbit." Information about an atom can be iteratively gathered by first examining immediate neighbors, then the neighbors of those neighbors, and so on.

However, the algorithm to generate ECFPs differs from the algorithms for Morgan/CANGEN in two important ways:

- Intermediate atom identifiers are stored.

- A completely unique set of atom identifiers isn't required, which enables many optimizations.

What is an ECFP?

An ECFP is defined as the set of all atom identifiers for each radius of perception up to the limit n. As the radius of perception expands (n increases), this set includes all identifiers found in both previous iterations and the current one. For example, the ECFP for n=0 consists of the set of unique atom identifiers. An ECFP for n=1 augments the members for the n=0 set with identifiers computed by examining each atom and its immediate neighbors, and so on.

As such, an ECFP atom identifier can be considered as a special kind of substructure key. Here, "substructure" refers to a central atom and its neighbors grouped by distance to the center. The presence of a key suggests that the corresponding molecule contains the substructure producing the key.

Atom identifiers can be stored using any convenient method. For example, some applications might use a set-like data structure such as the ones offered by the Set class found in ES6 and Python, or Java's java.util.Set implementations. Alternatively, probabilistic binary data structures such as Bloom filters and the like may also be used.

The View from 20,000 Feet

ECFP computation occurs in three stages:

- Initial assignment. Each atom is assigned an integer identifier.

- Iterative update. Atom identifiers are augmented with information gathered from the immediate atom neighborhood.

- Duplicate processing. Multiple instances of the same feature are either deleted or counted.

Simple ECFP algorithms can be developed from this description alone. For example, we might base ECFPs on atomic mass. In Step 1, we store the mass of each atom in a molecule within a set. This set becomes the Iteration 0 ECFP.

An Iteration 1 ECFP can be prepared by continuing the algorithm. To the already-obtained set of identifiers we add another group consisting of the sum of a central atom's atomic mass and the mass of its immediate neighbors.

Depending on specific application, duplicate atom identifiers may either be deleted or counted. If, for example, an application requires only the presence of an atom identifier to be recorded, duplicates can be deleted. If on the other hand, an application calls for counting identifier occurrences, a counter can be used.

We can iteratively continue to add identifiers up to any arbitrary radius of perception n. Notice that with increasing n, each identifier carries information about atoms ever further away from the central atom.

ECFP Computation Steps

The simplified algorithm described in the previous section omits a lot of potentially useful information. In practice ECFP atom identifiers will be derived from a much wider assortment of properties than just atomic mass. Below is an ECFP generation algorithm that can handle arbitrary atom and bond properties.

- Create a set (S) for storing atom identifiers.

- Label each atom with a 32-bit integer. Obtain this value by computing the CANGEN atom invariant, then hash the result (see: Hash Function).

- Add each atom identifier to S.

- If n=0, exit, otherwise continue to Step (5).

- For each atom, create a list of all bonds to neighboring atoms. Sort the list by (a) ascending bond order; and (b) ascending neighbor identifier.

- Using the sorted bond list from Step (5), prepare a feature list (F) composed of the following ordered list of elements:

n,identifier,bo1,aid1,bo2,aid2, etc, wherenis the iteration index (initially 1),boXis the order of bond X, andaidXis the current atom identifier for the neighbor attached to bond X. - Compute the hash value of the feature list from Step (6). This will become the atom's new identifier.

- Add the identifier to S, but only if it is structurally unique (see the next section).

- If further iterations are desired, increment the iteration counter

nand proceed to Step (5).

Structural Duplication

Atom identifiers exhibit two forms of duplication relative to the identifier set S. The first form relates to value equality. An atom identifier is only added to the identifier set if its value hasn't previously been added. This constraint will usually be enforced by the data structure being used to store identifiers.

Two identifiers may be unequal yet nevertheless equivalent, a situation called "structural duplication." Structural duplication arises when two identifiers represent the same molecular features. Structural duplicates must be identified and handled to avoid the introduction of useless noise into an ECFP.

It illustrate, imagine generating an ECFP for ethanol that disregards structural duplication. In the first iteration (n=0), atom identifiers for the methyl and hydroxyl groups are generated. At this point, there is no structural duplication.

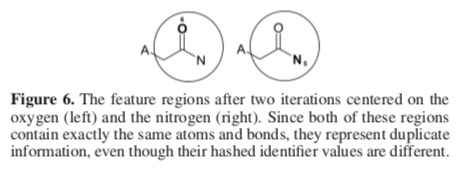

But the situation changes for the next iteration (n=1). Here, two new atom identifiers are generated. The first uses the carbon atom as the center of the radius of perception. The second uses oxygen.

Although two unequal atom identifiers are generated at this stage, they nevertheless cover the same set of atoms and bonds. Adding both identifiers to S doesn't increase the set's descriptive ability. For this reason, a method is needed to identify and either count or eliminate the structurally equivalent identifier.

The paper offers a slightly more complex example:

Rogers and Hall outline a procedure that can be used to prevent structural duplication. Each atom identifier added to S is associated with the substructure giving rise to it. Before a new atom identifier is added, its occurrence among the current members of the set is checked. If no match is found, the new identifier is added. Otherwise, a two-part procedure is used to decide which structural duplicate will be kept:

- Discard any new identifier if a structural duplicate from an earlier iteration is already present in S.

- Given two structurally equivalent identifiers generated at the same iteration, discard the one with the higher value.

Hash Function

Rogers and Hahn have this to say on the subject of the hash function to be used:

We do not describe the particular hash function used in our calculation because any "reasonable" hash function can be used, and the scientific validity of the results is equivalent. What is most important is to have the hash function map arrays of integers randomly and uniformly into the 232-size space of all possible integers; without uniform coverage, the collision rate may increase, leading to a loss of information. …

In other words, all that's needed is a hash function capable of generating identifiers evenly distributed over a sufficiently large range.

A good candidate is one of the cyclic redundancy check (CRC) functions such as the widely-used CRC-32. This hash function was first explicitly documented by Alex Clark for use in the Chemistry Development Kit's circular fingerprint implementation.

CRC-32 returns a signed 32-bit integer given an arbitrary byte array. Implementations are available for most languages. For example, the CRC-32 Node JS package works as follows:

import hash from 'crc-32';

const feature = [ 1, 2, 3, 4 ];

const identifier = hash.buf(feature); // -1237517363

Resonance

Like any fingerprint implementation, ECFP requires special attention to resonance forms. In particular, it's essential to generate the same ECFP for all resonance forms of the same molecule. Two conceptual approaches are feasible:

- Find a canonical resonance form before computing an ECFP fingerprint.

- Avoid using explicit bond information.

Of these two approaches, (2) appears the most practical. For example, two changes to the bond-specific algorithm outlined above would eliminate resonance form degeneracy. First, ensure that the atom invariant computation includes an atom's degree of unsaturation. Second, replace Step (6) with:

- For each bond in the list, prepare a feature list (F) in this order:

n,identifier,aid1,aid2, etc., wherenis the zero-base iteration index (initially 0), andaidXis the atom neighbor identifier computed in step (1).

Functional-Class Fingerprints

As the previous section illustrates, the base ECFP algorithm lends itself to modification. One of them, "Functional-Class Fingerprints" (FCFPs), is described in the paper. Rather than basing the original atom identifier on CANGEN properties, a six-bit code is used in which setting a bit indicates the presence of a "pharmacophoric" property:

- hydrogen bond acceptor;

- hydrogen bond donor;

- negatively ionizable;

- positively ionizable;

- aromatic; and

- halogen

A similar approach could be used to assign atom identifiers based on the presence of other feature classes, including graph properties (e.g., ring membership, hydrogen count, or stereochemical configuration), or physical properties (e.g., pKa, electronegativity, isotopic mass).

Naming Convention

Given the ease with which new ECFP variants can be created, a systematic method of naming them is helpful. Pipeline Pilot developed a two-part naming convention. First, a four-character base algorithm identifier is chosen. Two have already been mentioned (ECFP and FCFP). Others include SCFP (Sybil atom types) and aLogP atom codes (LCFP). The second part is a number obtained by multiplying the final radius of perception n by 2. The two parts are separated by an underscore ("_") character. For example, an ECFP accounting for atom type only would be called "ECFP_0." An ECFP including nearest neighbors would be called "ECFP_2," and so on.

Conclusions

ECFPs offer three features rooted in their construction that make them especially useful compared to other options:

- Simplicity. The base ECFP algorithm is composed of very few units, making implementation straightforward;

- Flexibility. Many variations on the base algorithm are possible;

- Readily Computed. The radius of perception can be changed to strike a balance between computational complexity and functionality