Billions and Billions

One of the things that makes organic chemistry such a fascinating and useful subject (not to mention profitable) is the way mind-boggling levels of diversity arise from the application of very simple rules.

In 1924, the American chemist Eugene Markush was awarded a new kind of patent (US 1,506,316). Rather than claiming manufacturing processes listing specific input materials, Markush claimed processes listing families of compounds as inputs - and pretty large families at that. For example:

The process for the manufacture of dyes which comprises coupling with a halogen-substituted pyrazolone, a diazotized unsulfphonated material selected from the group consisting of aniline, homologues of aniline and halogen substituted products of aniline.

The phrase "selected from the group" has since become the signature of a special kind of patent claim called a Markush claim. The approach significantly influenced the way chemical intellectual property was created and protected.

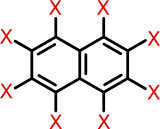

A Markush structure is a special kind of chemical structure in which variables are used in place of specific substituents. It turns out that even the most basic Markush structures can specify very large numbers of specific chemical structures. For example, consider a Markush structure specifying all halogenated naphthalenes:

To a first approximation, we can calculate the number of compounds specified by this structure with the formula:

5×5×5×5×5×5×5×5 = 58 = 390,625

To get the real number of halogenated naphthalenes, which would be less than 390,625, we'd need to account for symmetry of the enumerated structures.

Applying a Markush perspective to cheminformatics leads to some interesting product ideas. For example, a few years ago Coalesix released a computational tool called Mobius (screenshots) designed specifically to work with very large families of compounds encoded as Markush structures. And for years, patent databases such as MARPAT have been capable of searching the Markush claims of patents.

Given the centrality of Markush structures to the theory, practice, and law of modern industrial chemistry, it may be worthwhile to consider ways of incorporating the Markush perspective in to existing, or new, cheminformatics products and services.